Art and Magick in the 21st Century; Reflections of a Neophyte

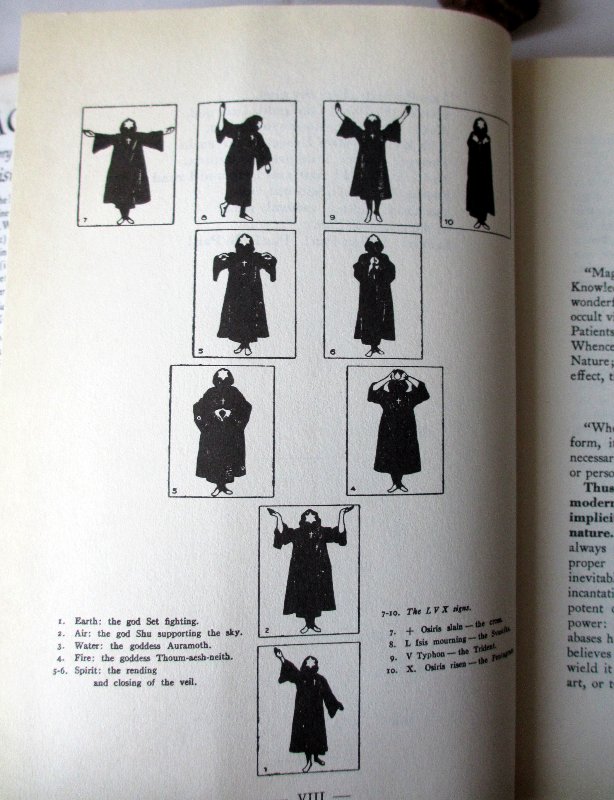

We are living in an era in which the word magic means something again within the sphere of art. While some artists adopt the visual trappings of magic as an aesthetic mannerism, others utilise their work in the service of magical practices, with the aim of achieving practical results. All share a desire to identify alternative ways of negotiating reality and looking at the world. This resurgence of interest amongst contemporary artists is echoed in the fields of art history and academia. This is notably manifest in the recent wave of recuperative exhibitions that posthumously revisit the oeuvres of artists, revealing how occult activities or esoteric organisations directly shaped their work (1). In her notes outlining the curatorial rationale for TACTICAL MAGIC, Kerry Guinan states that in the context of this exhibition, magic is ‘not so much about abstract spirituality, or inward journeys of the self, but is rather viewed as a tool created for a particular use’ (K. Guinan, personal communication, September 19th, 2019). This definition evokes one (of several) given by Aleister Crowley in his 1929 book Magick in Theory and Practice. In this book Crowley defnes magick as ‘the Science and Art of causing change to occur in conformity with Will (2). Initially Crowley was affiliated with the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn, one of several orders responsible for the magical renaissance of the late 19th century. Founded in England in 1887, the Golden Dawn reinstated the idea that magic could have real and practical applications in all matters of human life (3). This revived magical practices which had been relegated to the fringes for centuries. As late as the 16th century, certain forms of magic were not only viewed as credible, but were also closely aligned to more mundane forms of science. This is evidenced by figures such as the legendary John Dee (1527- 1608/09) who advised Queen Elizabeth I. However with the rise of the ‘rational’ sciences that provided quick and quantifiable outcomes, the ritual and symbolic elements of magic came to be viewed as suspect and were ultimately jettisoned during the Enlightenment.

The Golden Dawn was one of several organisations that heralded a new age of magic and spurred many members (of which W.B. Yeats and Maud Gonne were included) to found their own magical organisations. The period saw the emergence of many occult orders founded by those who wished to bring together a constellation of practices and proclivities as exemplified by Crowley establishing his system of Thelema (4). The repositioning of magic is demonstrated by Crowley’s attempt to reclaim and distinguish magic from its associations with entertainment and illusionism by adopting the spelling magick. It is significant to the subject of this essay that Crowley viewed his work as an artist (producing paintings and poetry) as inextricably intertwined with his magical practices. Moreover, Crowley believed that the power of one’s will and mental focus was vital, and viewed magick as an agent of the psyche. These are some of the factors that make Crowley’s contribution to the development of modern magick pivotal, and his influence continues to be felt in the 21st century. Another notable example in the context of TULCA is that of Austin Osman Spare (1886 –1956) whose art practice and spiritual life are, like Crowley, indivisible. Notably, Spare too viewed magick as being rooted in the psyche of the practitioner. Rather than summoning angels or demons, the aim was to harness the mind and its latent powers. Spare was also a pioneer in his use of sigils. In the Medieval era, a sigil was the symbol used to denote and evoke a particular demon. Spare personalised this system and began to devise symbols that represented his own desires and needs. This process is illustrative of the psychologisation of magick at this time and was particularly important to the formation of Chaos Magick later in the twentieth century (5). Formalised in the late 1970s, Chaos Magick is staunchly subjective, DIY and built upon the individual’s desire to realise very specific outcomes. Crucially, Chaos Magick is not built upon a codified system but is intended to be constructed by the individual, and having emerged as it did in the late 1970s, it can also be seen possessing postmodern tendencies that also typify the art forms of that period; pastiche, irony and bricolage. Its potency as a cultural catalyst has led to it informing much of the thinking behind this year’s TULCA, as well as the practices of the collective ‘Center for Tactical Magic’ (CTM), which shares the festival’s name.

A pioneering researcher investigating convergences between occultism and contemporary art is Dr. Marco Pasi who has been analysing the tendency towards magic in contemporary art for over a decade. In his 2010 essay Coming Forth By Night, Pasi discusses the early phases of this tendency which has perhaps now reached its apogee. In his exploration of the various ways contemporary artists have embraced magical vocabularies and practices, Pasi emphasises that esotericism is a sphere comprised of various facets, many of which are motivated by distinct and often contradictory concerns. Pasi categorises four main tendencies of how engagement with the occult or esoteric may take place in contemporary art. These are instructive and worth considering, hence my including a substantial excerpt of Pasi’s text below. Undoubtedly, these tendencies can be found in various combinations in the work of the artists participating in this year’s TULCA festival. “I see four main ways in which the relationship of the occult with (contemporary) art can present itself. The first is the representation of esoteric symbols or images associated with esotericism. This takes place of course at the most explicit level of visual language, and is based on the legacy of esoteric visual lore which has a very long visual history of its own. The second is the production of artistic objects (picture, sculpture, installation, etc.) that can be interpreted as talismans or fetishes or in manipulating matter that can be associated with occult sciences such as alchemy or magic. In this case, the object is the final step of a magical procedure and/or is endowed with magical powers. The third way is when the artistic work becomes a means to induce extraordinary experiences, which can be interpreted as having spiritual / mystical / initiatory / shamanic / magical / qualities. This has of course particular significance in the context of performance and body art. Some of the ingredients of extreme art performance, such as pain, fear or narratives of death and rebirth have also been traditionally associated with esoteric initiation and mystical experience. Finally, the fourth way is when the artistic work is the result of a direct inspiration / communication from spirit entities or of a visionary / mystical experience (6)”.

When Pasi’s essay was published in 2010 this ‘esoteric turn’ in the sphere of art was well underway. However, even at that stage the extent to which artists would adopt this approach was not apparent. Magickal practices would go on to be used in the service of activism and protest, resonating in particular with artists working with queer and feminist practices and methodologies. Alongside Chaos Magick, the practices of Wicca have also been embraced by contemporary artists (7). This is a testament to the eclecticism of these practices and the flexibility of the methods they offer; which can be adopted and modified subjectively. Furthermore, the nonhierarchical and non-centralised structures of these paths ensures that they continue to flourish in our internet age, having been adopted by legions of artists who wish to subvert dominant forms of knowledge. The work of South African artist Linda Stupart, epitomizes how strategies appropriated directly from magickal practices are being utilised within contemporary art contexts. Stupart authors and performs spells with titles such as ‘A spell to bind straight white cis male artists from getting rich of of appropriating queer aesthetics and feminine abjection,’ ‘a spell to bind Richard Serra,’ and ‘a spell for binding a super trendy sexist hot young male artist’s internet access’ (8). The late Chiara Fumai (1978 – 2017) used practices infuenced and adapted directly from chaos magick and combined them with elements appropriated from radical feminism, terrorist propaganda, and Italian Autonomist Marxism. A reconstruction of one her final works (entitled This last line cannot be translated) was presented posthumously for the first time in the Italian Pavilion at this year’s Venice Biennial (9). This expansive wall mural integrated an invocation known as the ‘Mass of Chaos’ (10). and demonstrated how in her later work she was particularly interested in using sigils in her work in a manner that was directly influenced by Austin Osman Spare and Thee Temple ov Psychick Youth (11).

The work of artists such as Stupart and Fumai exemplifies how contemporary artists are actively performing practical magic. At the same time others use archetypes borrowed from the mythos that surrounds it symbolically to give representation to feminine power and the rejection of traditional gender roles. This approach is demonstrated in the multi-media exhibition Tremble Tremble by Jesse Jones which constituted Ireland’s presentation at the 2017 Venice Biennale (12). The central facet of the work is a flm presented on a cinematic scale, depicting a witch or wise woman figure (performed by Olwen Fouéré) speaking straight to the camera. Her monologue is both a supernatural invocation and a political polemic; she urges all to ‘reject the law that all men follow.’ The title refers to a slogan chanted during Italy’s Wages for Housework campaign of the seventies: “Tremate, tremate, le streghe sono tornate! (Tremble, tremble, the witches have returned!”). In making this work Jones was influenced significantly by Sylvia Federici’s groundbreaking book dating from 1998 entitled Caliban and the Witch: Women, the Body and Primitive Accumulation. Te monologue also makes reference to Irish legislation, which in those pre-repeal days continued to criminalise women for having abortions in most circumstances. By channeling and reinforcing the sentiments of historical and contemporary social movements, Jones’ witch underscores the idea that organised dissent has the capacity to transform reality. The writings of Federici were also of importance to Kerry Guinan in her preparations for this chapter of TULCA and a reading group led by Jones is scheduled to take place during the festival.

The constellation of artists embracing methodologies of magick is as diverse as their work is different. However, they are for the most part unified by the impulse to transcend and resolve some of the inequalities and injustices that beset our current condition. Magick today is imbued not only with a sense of possibility but also insurgency. There are still those who look back to particular episodes from the past with nostalgia and try to reconstruct crepuscular scenes from periods in which magical revolutions occurred, such as the 1890’s or 1960’s. However, most artists that I have encountered who have adopted magical disciplines are of a far more radical bent; they look ahead and construct systems that enable them to protect and survive in these bleak and turbulent times. Whether it be circulating sigils on the internet, convening covens for ‘public hexings’ or simply repurposing one’s smartphone as a scrying mirror, the vocabulary and vitality of esotericism has been reawakened. In this, the second decade of the 21st century, magick offers catalysts for generating community and symbols with which oppressive and outmoded structures can be undermined. TACTICAL MAGIC is just one of many occurrences taking place in the world of contemporary art that reminds us that both art and magick have similar origins and can satisfy similar needs. Art -like magick- offers us tools that enable us to create alternative forms of knowledge and provides us with skills to persevere in an old world whilst conjuring up a new one.

1 This is demonstrated by the cases of Georgiana Houghton (1814-1884) and Hilma af Klint (1862-1944). These artists were influenced more by their engagement with Spiritualist and Theosophical organisations, as opposed to magickal orders, but nevertheless, they can still be viewed as having been significantly influenced by esotericism.

2 Aleister Crowley. Magick, Liber ABA, Book 4, First published 1930. Corrected edition included in Magick: Book 4 Parts I-IV, York Beach, Maine: Samuel Weiser, 1994.

3 The Golden Dawn was founded by William Robert Woodman, William Wynn Westcott and Samuel Liddell Mathers all of whom were Freemasons.

4 Crowley developed Thelema in the early 1900s following a spiritual epiphany that he claimed to have had with his wife Rose Edith Kelly in Egypt in 1904.

5 Chaos Magick was formalised in the late 1970s with the publication of Ray Sherwin’s

The Book of Results in 1978 and later Peter Carroll’s Liber Null in 1987.

6 Marco Pasi ‘Coming Forth by Night. Contemporary Art and the Occult’, in: A. Vaillant (ed.), Options with nostrils, Rotterdam: Piet Zwart Institute 2010, 103–111.

7 Wicca originated in the early decades of the twentieth century among several esoterically inclined Britons who wanted to resurrect what they viewed as the faith of their ancient forebears, and arose to public attention in the 1950s and 1960s, largely due to a small band of high profile followers.

8 These spells by Stupart can be accessed via her website: http://lindastupart.net/Spells.php

9 The Italian pavilion at the Venice Biennale also featured works by Enrico David, and Liliana Moro and was curated by Milovan Farronato.

10 An invocation found in Liber Null & Psychonaut (1987) by Peter J. Carroll.

11 Thee Temple Ov Psychick Youth (aka TOPY) was a magick fellowship founded in 1981 by several artists of which Genesis Breyer P-Orridge is perhaps the most renowned.

12 This exhibition by Jones later toured to venues in Singapore, Dublin and Edinburgh.