An t-Imeall

An t Imeall

“There is a boundary to men’s passions when they act from feelings; but none when they are under the influence of imagination”.

Edmund Burke.

“An tImeall”, the title of Sinéad Ni Mhoanaigh’s third solo show – like that of her preceding exhibition “Eatramh” (September 2006) – is riven with ambiguity. Catherine Leen notes that this previous title can refer to intervals or voids in either space or time and, similarly, this latest title (meaning the edge, the verge or the border) suggests not only the notion of geographical distinction but also calls to mind the notion of the time related periphery. Apt are these limitless titles for paintings that are as elusive as they are explicit – their subject and disposition remaining forever on the border, mysteriously on the edge of what they are not and what they could be, evading definitives…

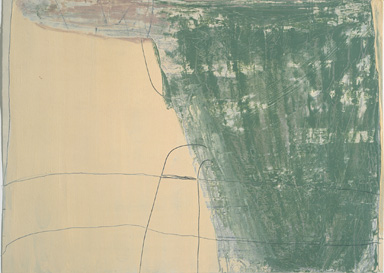

Present in these new works are echoes of the vague constructions, frames and vessel motifs which typified Eatramh (and some of these new paintings do feature the same activated spaces and anomalous constructions of that previous show) but there is now a greater emphasis upon the delicate balance struck between non-representational and emblematic imagery. Occasionally, the alluring suggestions of landscape within the paintings demand that they also be read as allusive, even referential, to the material world. Although one may be reluctant to read these magnificent paintings as anything but ‘pure painting’, they seductively proffer invitations which suggest they may be read figuratively – their shapes and ‘non shapes’ occasionally appearing like ancient prehistoric monoliths which (typically of Ni Mhoanaigh’s two-fold aesthetic) can also appear like naïve renderings of garishly-hued industrial landscapes.

This phenomenon is apparent in “Outline”, in which the silhouettes of forms are suggestive of colossal silos or storage containers, and in the subdued “Stage III”, which is similarly evocative of environments within the familiar physical realm and constitutes a magnificent climax to a series, of which the first and second parts appeared in Eatramh. These ‘stages’ – a series of abstract works formally demonstrating evolution and development – also represent naïve renderings of podiums or platforms before or after a performance. While I and II seemed to depict the phases of ‘preparing’ the stage for show, this final image suggests conclusiveness – the ‘curtain’ of heavy brown smothering any potential for further action. Even though these compositions of autonomous forms and intoxicating colours – hovering on the edge of absolute abstraction – are wholly satisfying, the intimation of literal representation is too strong to ignore.

Primarily investigations of the emotional power inherent in ‘non shapes’ the vessels and elliptical objects seen in “Pilgrim II”, “Untitled” and “Vessel” nevertheless also imply processes of gestation and development. This is appropriate considering that each painting is clearly the manifestation of accumulated action – abounding with signs and notations of its own production. Each exposed hue signifies reminiscences and events which have been superseded and overlaid with fresh layers of new process and experience. Sometimes, incised excavations expose whole planes and forms submerged under concealing exteriors. In Foreground II contrasting colours from previous applications reintroduce themselves back into the Now like flashes of memory prevailing. The presence of impulsive gesture in the work is married to and contrasted with evidence of long gestation – both made visible by the excavated echoes of previous stratum underneath the epidermis. Hence these works repeatedly and deliberately divulge the ‘presentness’ of their previous form.

The seductive attraction of the paintings lies in their extrovertly taciturn quality, and by the way in which the gutsy, even aggressive application of colour is countered by the sensitive, even delicately tentative, scoring of the paint in all its precise and potent hues. Rare is it to see paint being worked so sensually and yet often so brutally. The juicy colours push and pull, and the eye is caught in an impossible impasse – are we gazing onto boundless unlimited and infinite space, or are we peering into claustrophobically constraining, sealed and hermetic compartments from which nothing can leak? Can we, simultaneously, do both?

Ni Mhoanaigh’s involved and tactile approach – with its implications of cathartic release and metaphysical intensity – generates images that, packed and agitated as they are, ultimately function as investigations into the sublime. Kant split his concept of the sublime into three categories: the petrifying sublime, sometimes accompanied with a certain dread or melancholy; the noble sublime inspiring quiet wonder; the splendid sublime, pervaded with beauty. One need only gaze at Ni Mhoanaigh’s paintings – packed complex, luxurious, transfixing – to see a simultaneous evocation of not one but all these facets of the sublime, held perpetually in tension and in unison.