Splendid Isolation

In 1972 curator Harald Szeemann presented the then little-known art brut of Swiss artist Adolf Wölfli alongside works by world-renowned artists in Documenta 5, and Roger Cardinal published his groundbreaking book Outsider Art, drawing attention to a constellation of visionaries and self-taught makers. In the half-century since, formerly arbitrary definitions of what constitutes contemporary art’s inside and out have grown more porous, and this exhibition at SMAK is the latest contribution to that process. Prompted by the enforced confinements of recent years, it’s a wide-ranging reflection on isolation and its psychological and cultural repercussions. Only a handful of the 22 artists here could be considered ‘outsiders’ in the original sense of the word: indeed, this show includes established artworld names such as Louise Bourgeois, Derek Jarman and Nalani Malini alongside lesser-known and local figures. But what unifies this heterogenous group is that they have all been sequestered from society in some way, whether through metaphorical ‘outsiderness’ or literal isolation.

Their circumstances and fortunes, though, vary dramatically. Some withdrew voluntarily in pursuit of an ascetic existence, such as Guernsey-born Benedictine monk and concrete poet Dom Sylvester Houédard, represented here via several collages and ‘typescripts’. Others, such as the the sculptor Judith Scott, who was born deaf and with Down Syndrome, were marginalised as the result of a disability. And in several instances works were made in response to places of captivity, as exemplified by the wistful paintings of the reclusive David Byrd, who worked as attendant in a psychiatric ward.

Elsewhere, the extent to which punishment and imprisonment shape our society is indirectly highlighted by works depicting the dehumanising reality of being locked up or living under martial law. In 2017, the aforementioned Kurdish artist Zehra Dogan was jailed for almost three years, having been charged with ‘terrorist propaganda’ after she shared images, on social media, of her painting portraying the devastation wreaked by the Turkish military on a mainly Kurdish village in southeastern Turkey. The series of drawings on display here captures the brutality of prison life and possess the quality of a graphic novel, with narratives presented in sequential frames. There is an element of reportage to Dogan’s work, but this is ultimately a form of storytelling that uses animal imagery and symbolism and to further accentuate the full extent of injustices she and others have been subjected to.

A storytelling impulse also governs the work of Shuvinai Ashoona, an Inuit who spent much of her early life in remote outposts of Canada’s Northwest Territories. Ashoona’s drawings offer insights into her everyday life, but also feature visionary details that evoke nature myths. In Composition, Woman Battling Walrus, Elephant, Octopus and Bird Creature (2019) a woman is pictured from behind wrestling a chimerical hybrid of the named animals. Ashoona’s impressions represent both her individual experiences and, on a more universal level, also revivify voices and worldviews previously marginalised by the long-term cultural homogeneity imposed by settler colonialism.

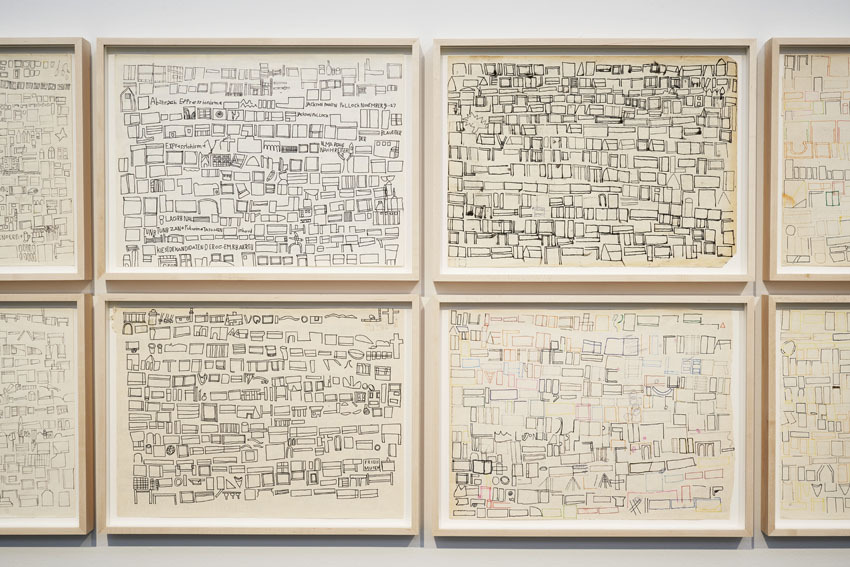

In bringing together such a diverse assembly of artists, Splendid Isolation reveals commonalities and shared tendencies, rather than fetishising or reinforcing otherness. It’s evident that all of the works here were made out of necessity: to make art as a means of sublimating or communicating. The majority of works here, most of which are wall-based, possess a distinctly handwrought quality produced via manual processes such as stitching and drawing , which lends a distinctly intimate and human character. Additionally, while many of the inclusions show a propensity for figuration and narrative content, some of the most intriguing pieces employ abstract vocabularies or self-devised systems of notation. Belgian artist Danny Bergeman’s idiosyncratic drawings – consisting of grids of geometric forms, seemingly intended to demarcate time’s passage or to record observations, and hung in a monumental installation – were produced daily over a seven-year (2011-18) period at De Zandberg, a welfare organisation established for artists with disabilities . The potency of Bergeman’s work stems partially from its formulation and execution according to criteria we are not party to; nor need we be to glean something valuable from it. Like many of the creations here that emerged from margins and solitude, Bergeman’s work possesses an intensity and unselfconsciousness that, even in art’s now-expanded purview, are all too rare.