Back(s) To Nature

Age of millenarian environmentalism

This is the age of millenarian environmentalism. Since the beginning of the decade numerous governments have declared a state of climate emergency in quick succession. Simultaneously, there has been a flourishment of grassroots movements forming in response to climate change. The revelation that we are reliant upon fragile ecosystems that we are also destroying is not new. However, this awareness has grown in recent years as the magnitude of our dilemma grows more acute. At the same time, the dominant religious and philosophical structures that bolstered society in the West are in terminal decline. The upshot of all this is that for a great many people today the cathedral of nature seems the last bastion of solace. In the face of societal fragmentation and inevitable collapse, legions seek sanctuary in the potential of deep ecology.

Considering life in more expanded ways

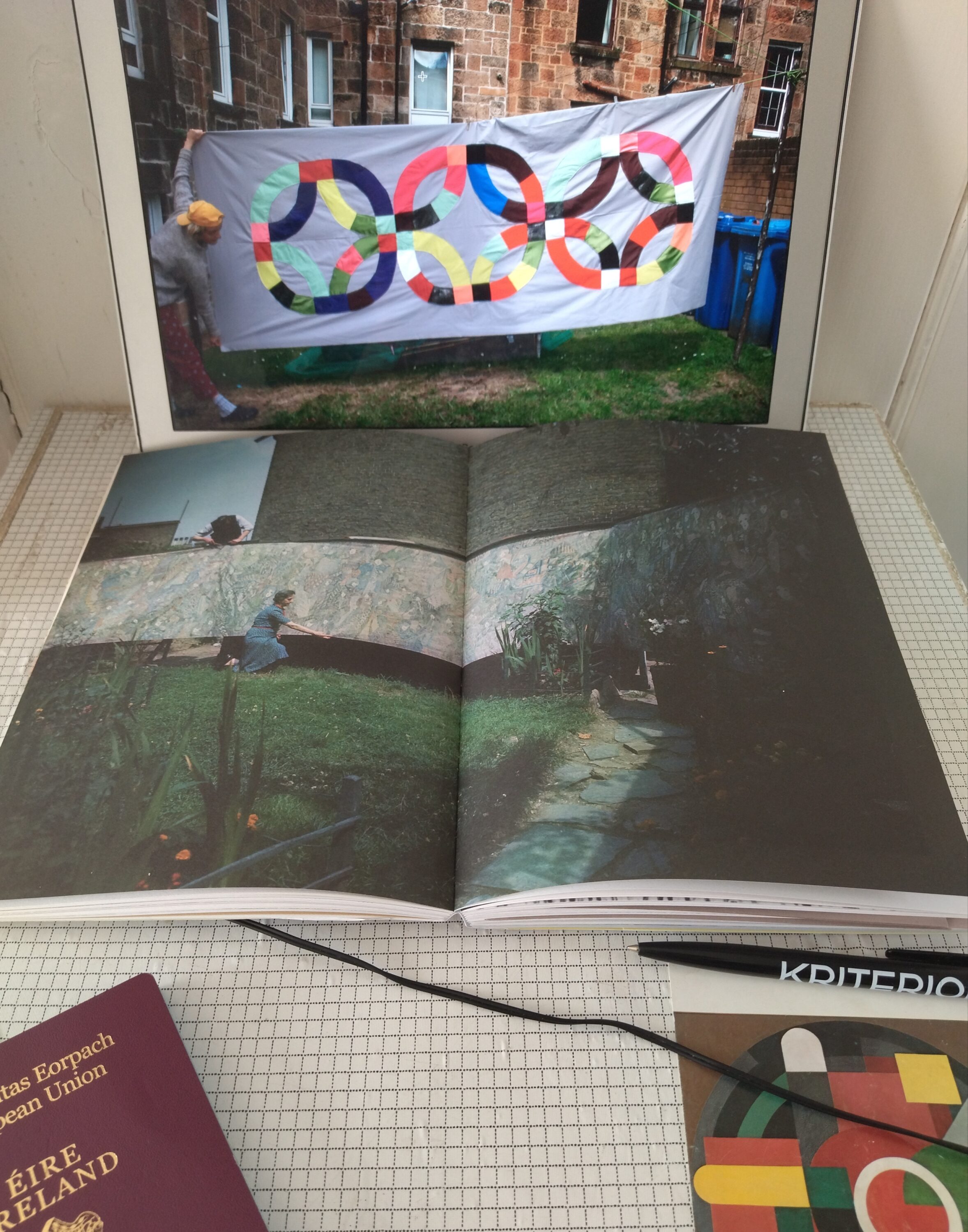

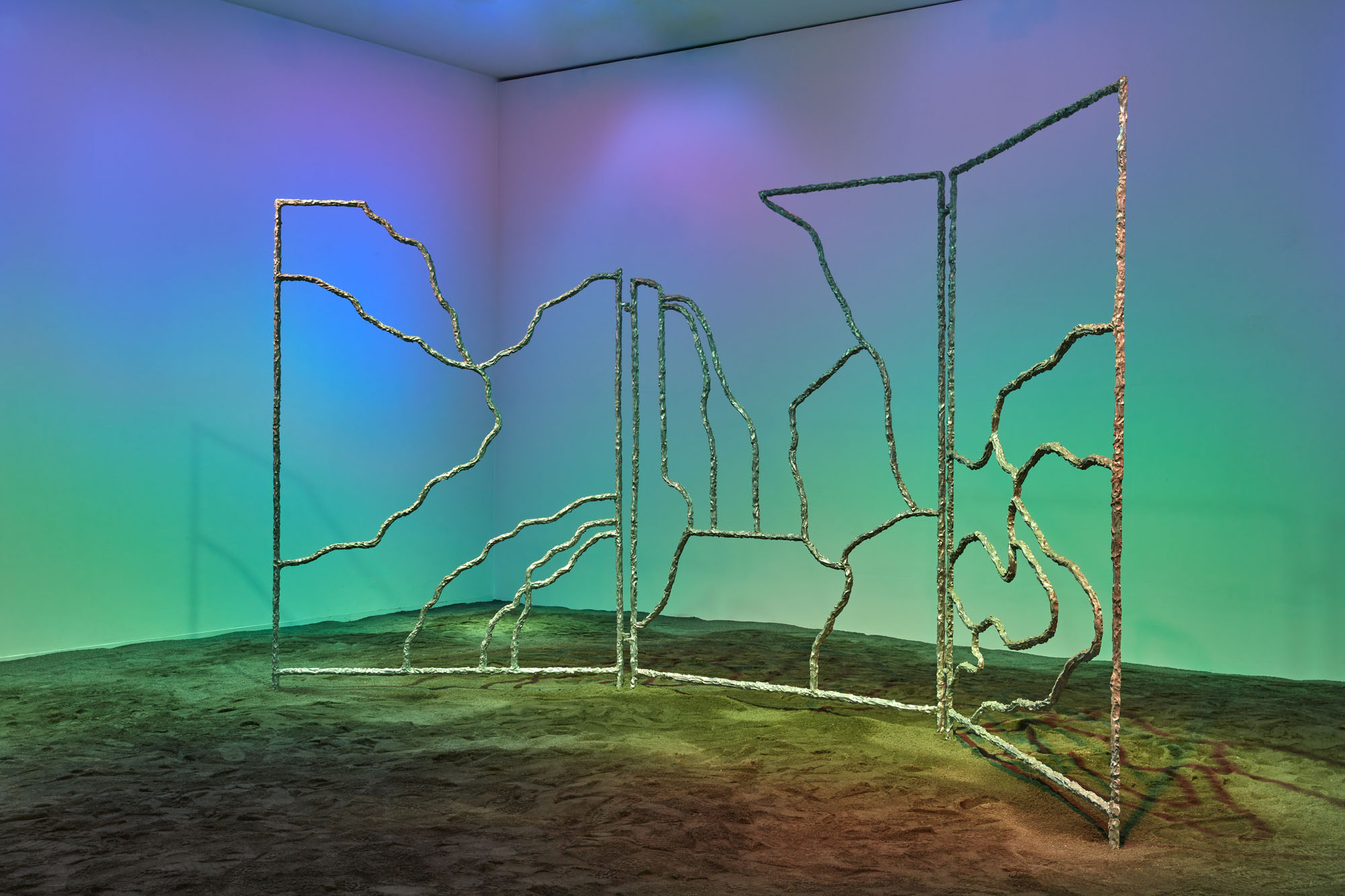

Caoimhín Gaffney’s exhibition All At Once Collapsing Together exemplifies the tendency of going back to nature for solace. The thinking behind this exhibition was informed by experiences of venturing into non-urban and rural places during the rolling lockdowns that started this decade. Like many, Gaffney sought refuge and equilibrium in such places during that febrile time. While this allowed Gaffney to consider life in more expanded ways but also brought an awareness of the extent to which our planet has become irrevocably disordered via human intervention.

Although initially salved by ventures into nature, Gaffney began to see evidence everywhere of the extent to which the environment has become forever sullied. They describe a bleak realisation that “seasons and growth cycles had become disregulated” and that “they were in in a state of total flux and shift[1]”. Ultimately, the binding quandary we find ourselves in as a species informs this show; whereby “on one hand we have a climate crisis and on the other our sense of self, our identity – even our health (as a species and as individuals)- is dependent upon our relationship with nature.[2]”

An interwoven environment

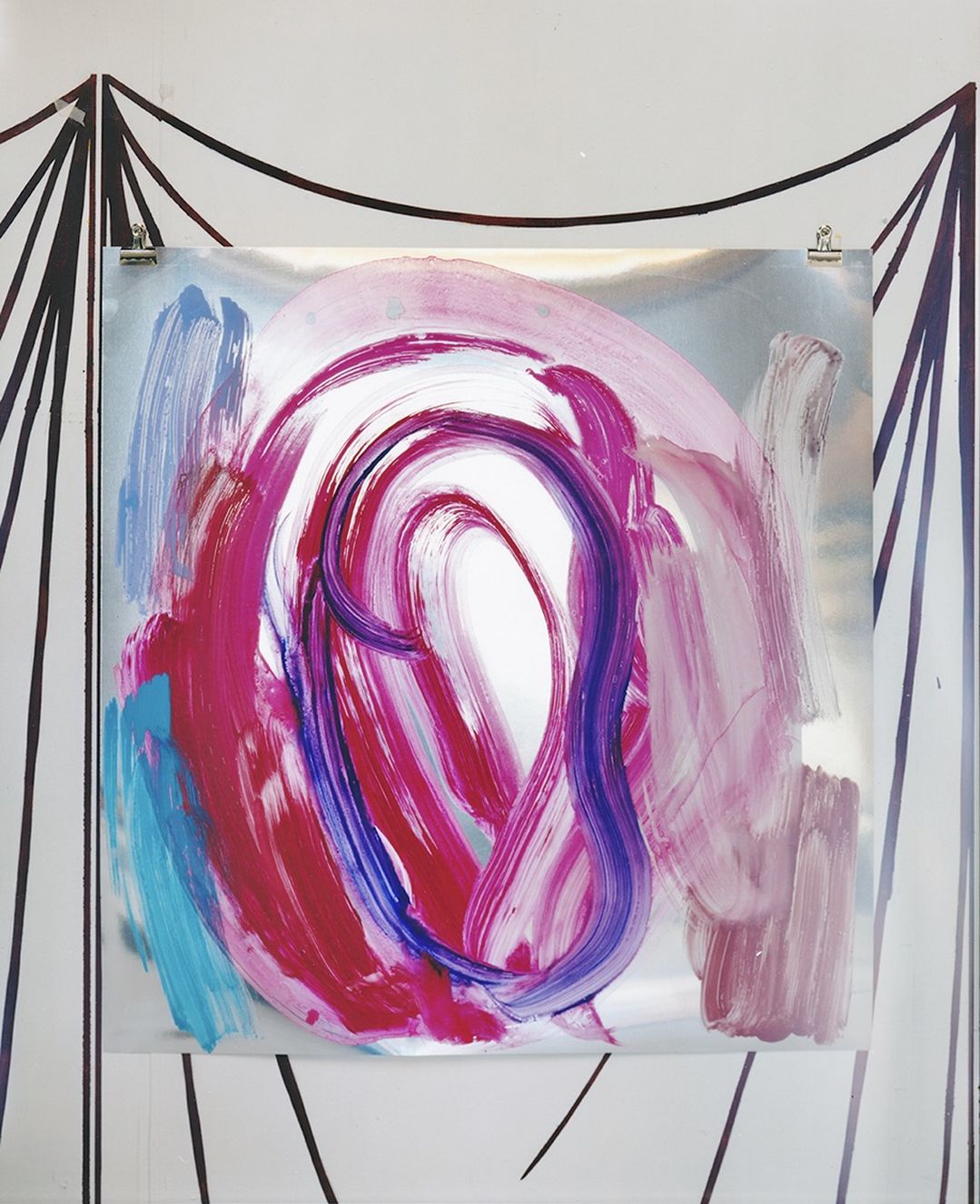

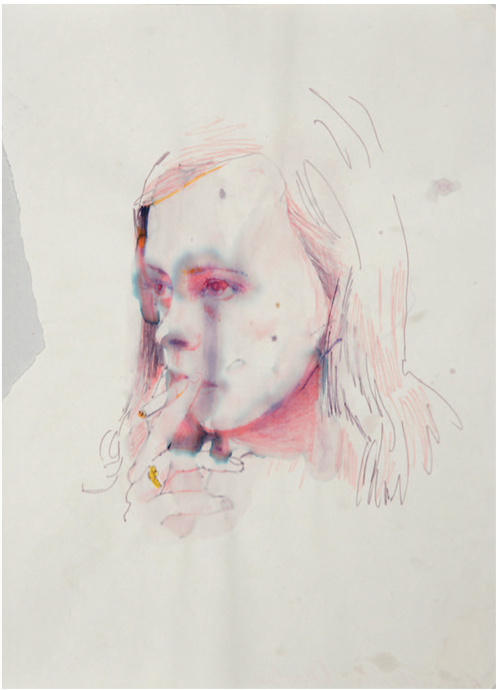

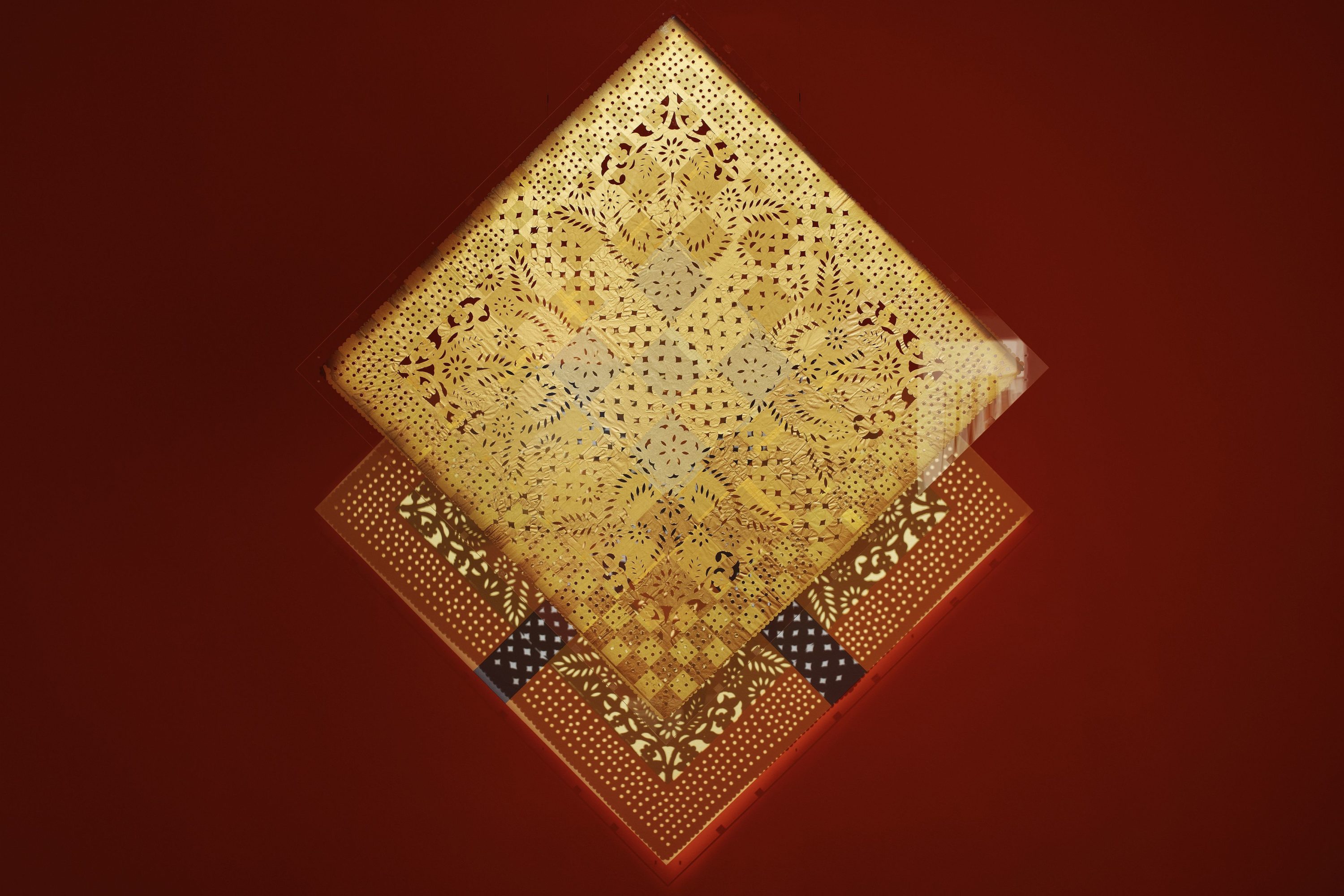

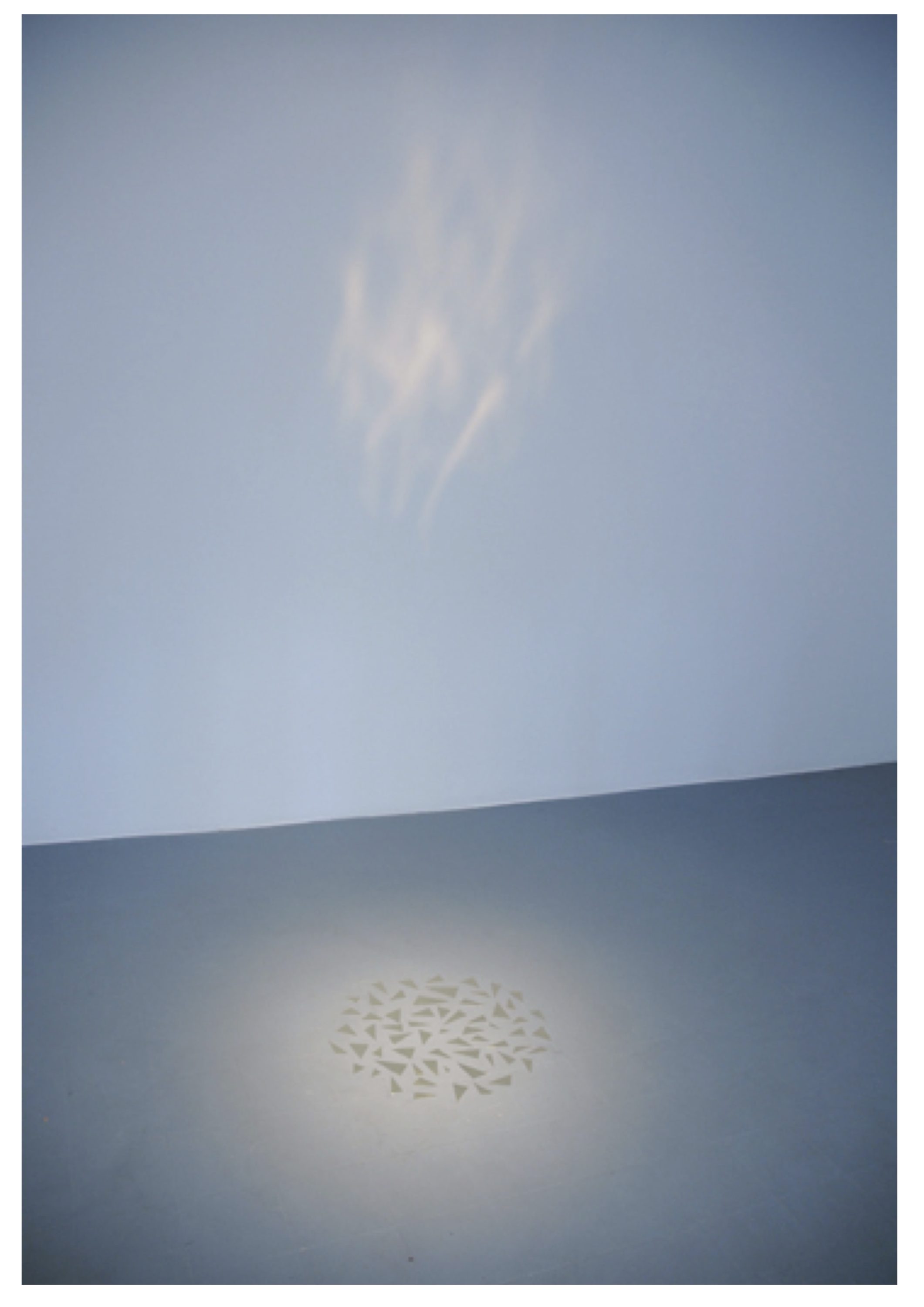

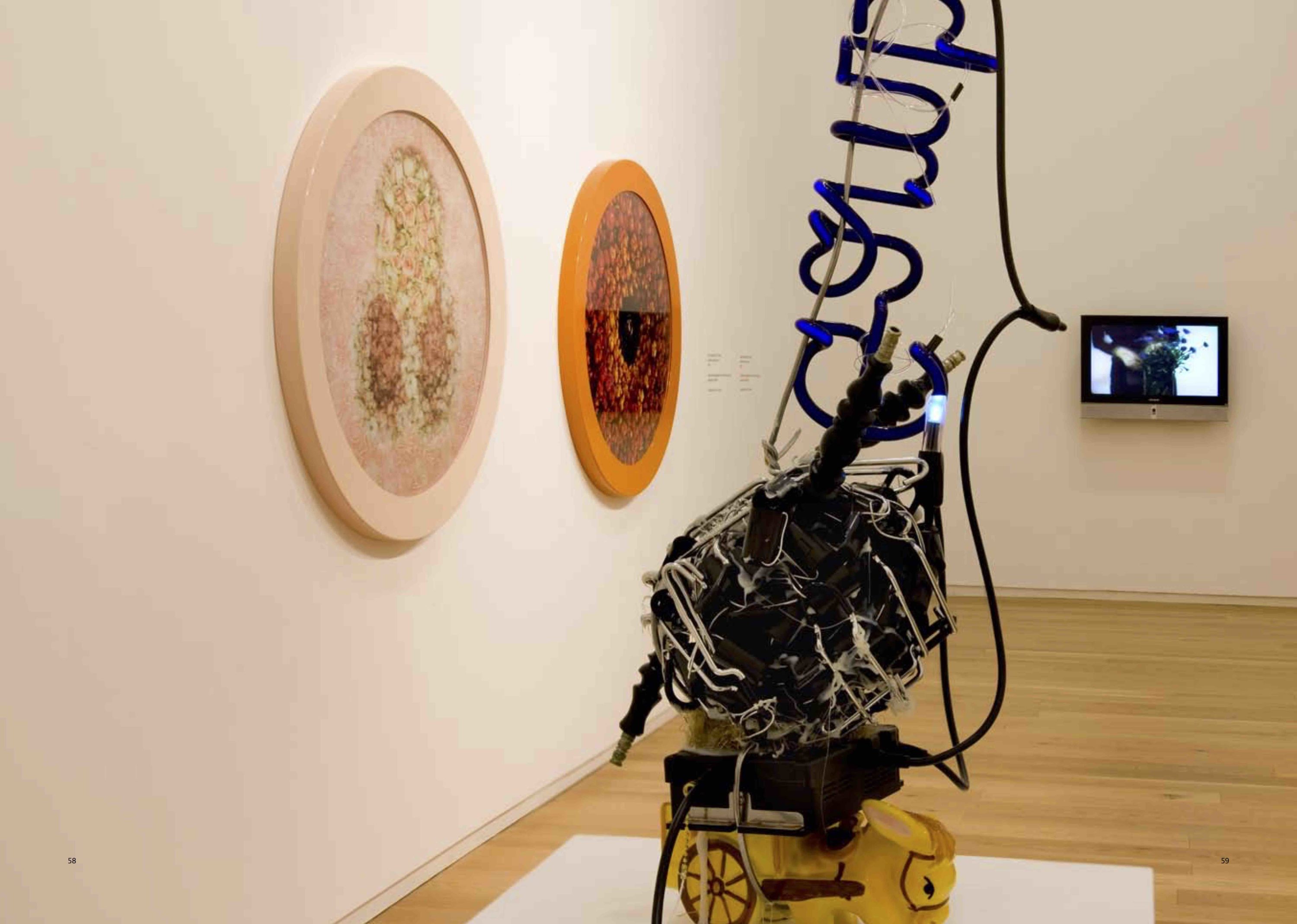

Gaffney is an artist with a notable facility for using language. When speaking or writing about their work, words are measured and precise. But this is the first time words -in the form of poems and shorter phrases -some of which are presented as neon- have featured so directly in their work. Known primarily heretofore as a maker of photographic images and films, this exhibition sees Gaffney enter more expanded territory. Composed of interrelated elements, it is essentially an enveloping environment, as opposed to a body of discrete components. A key component here is the neon text sculptures which the artists describes as “floating ideas[3]”. These three works in red, yellow and mauve create chromatic washes; imbuing the space with atmosphere that fuses together the other ingredients: an array of photographs and printed textual pieces and the two channel film, from which this exhibition takes its title.

The writing in the show- whether in printed texts or spoken in the film- is lyrical and poetic. Yet, their often direct and personal address presents images that are uncanny and disturbing; which nature is humanised and given a voice with which to chide us. One particularly notable image that is evoked in Gaffney’s film is that of a body preserved in plastic vacuum packing and sacrificially sent down a river. Images such as this which are summoned by Gaffney either visually and via language are potent and it’s evident that producing this work holds cathartic potential for the artist. They state how “I’m interested in an excess of feeling, or taking it as a challenge to express a feeling or sensation I don’t have words for yet. I like to write from different perspectives- where there’s not a narrative voice that holds everything together. So, rather than sidestep the uncomfortable… to step right into it”.

The multifaceted entity we name nature

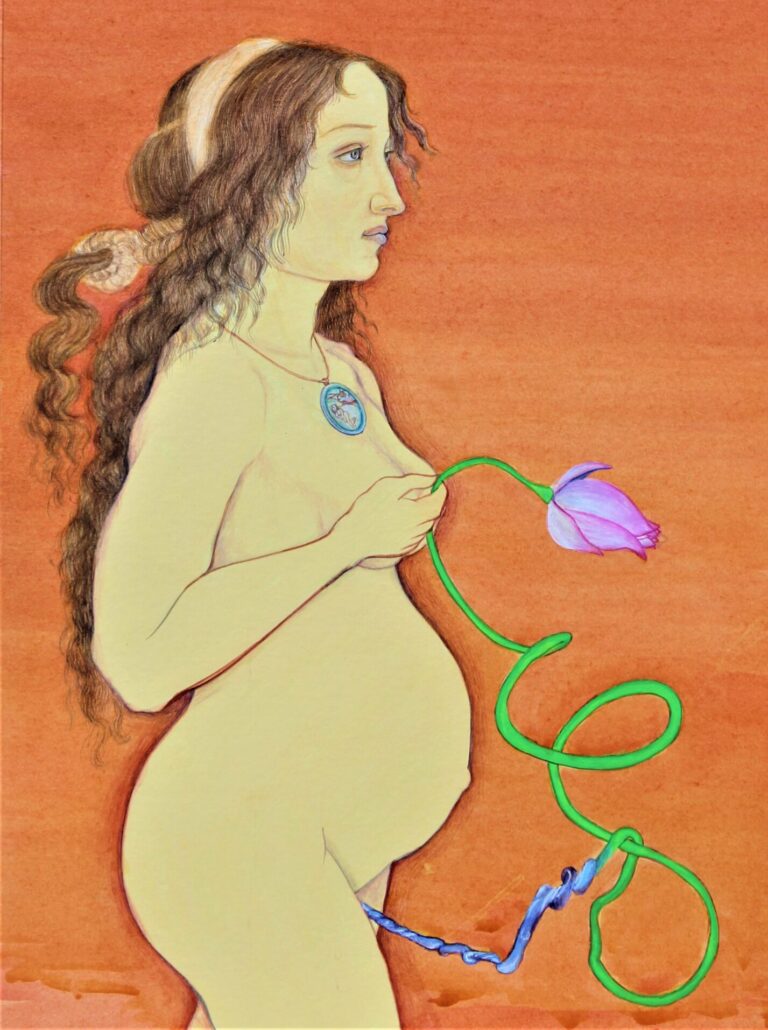

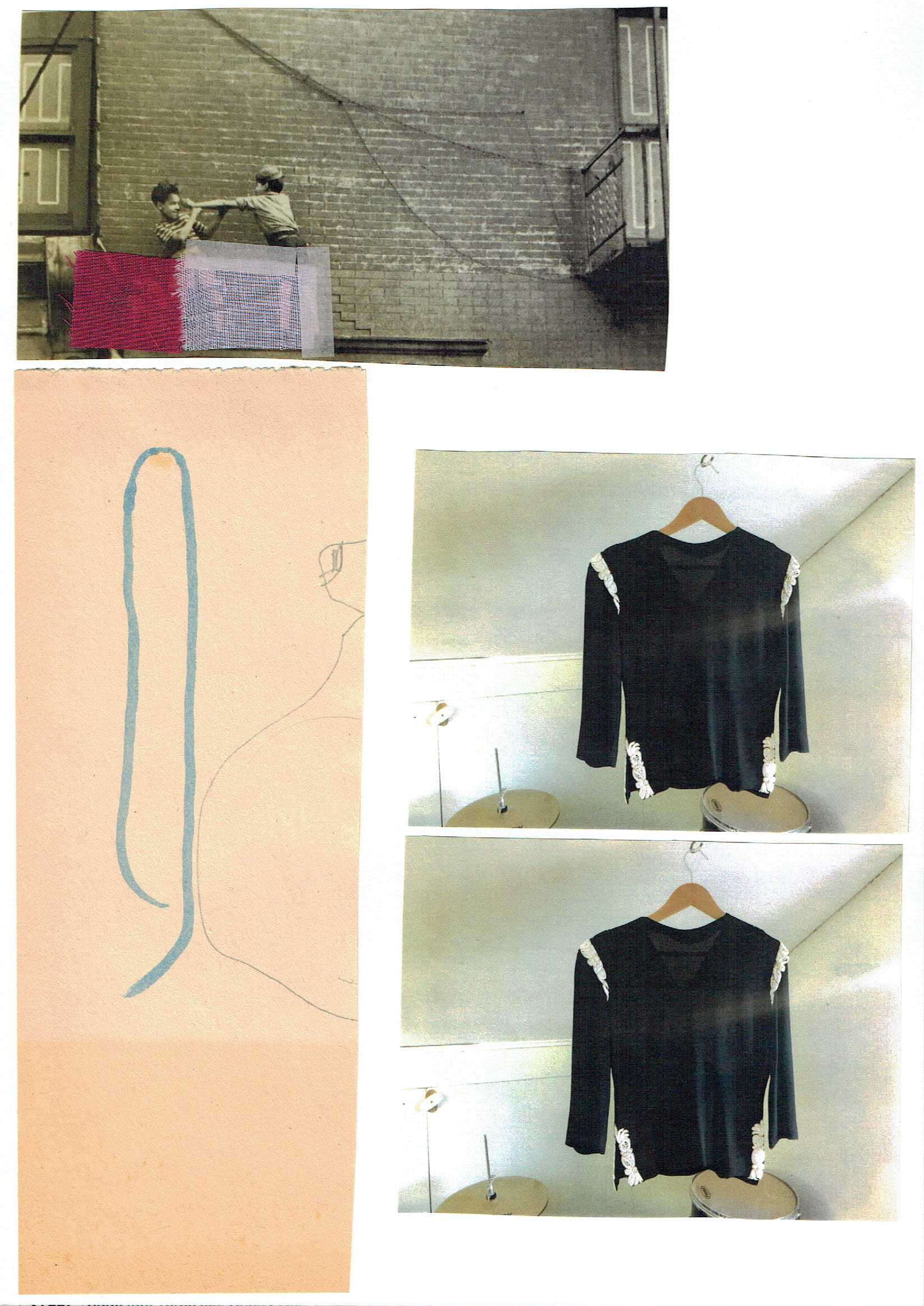

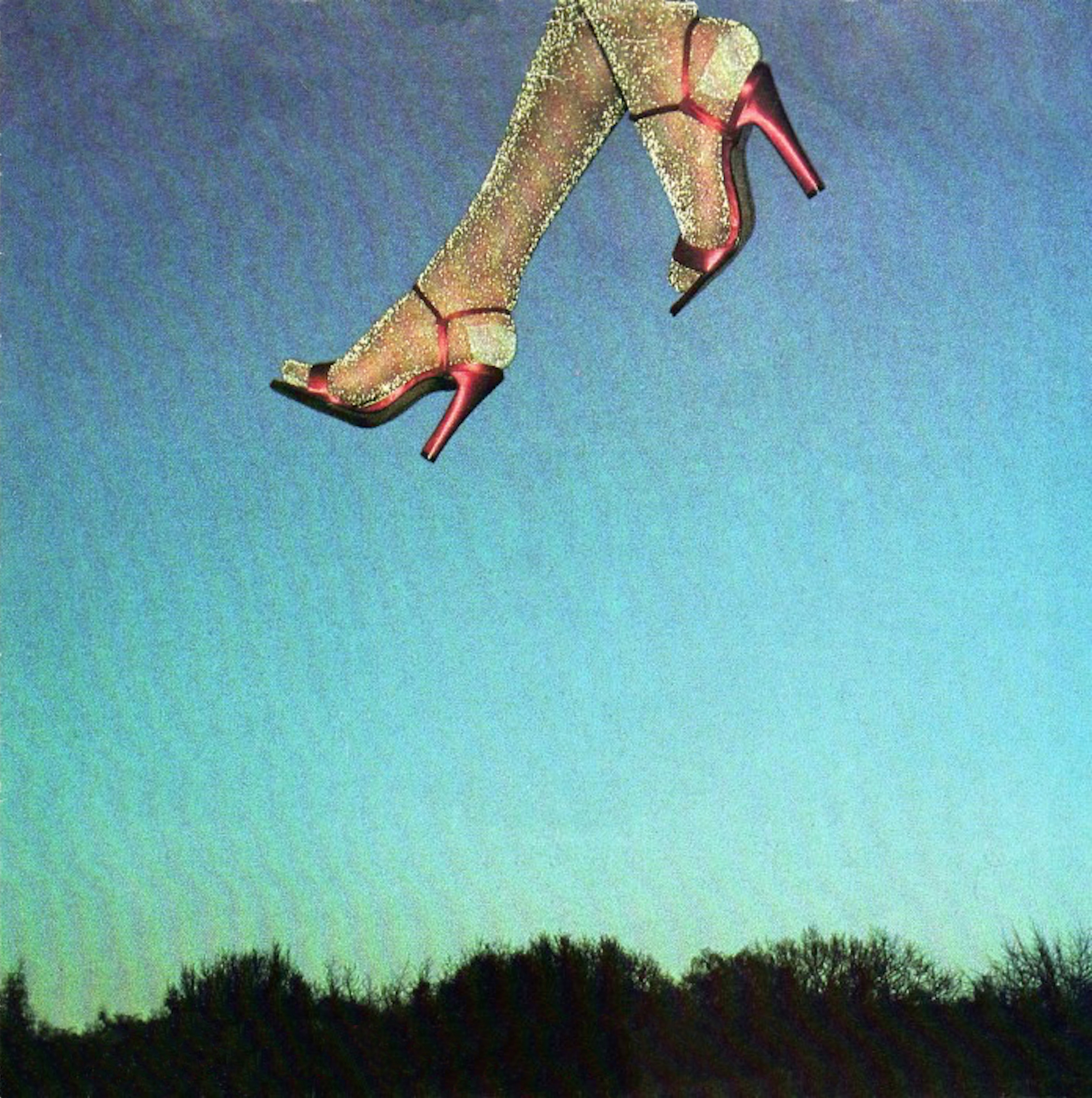

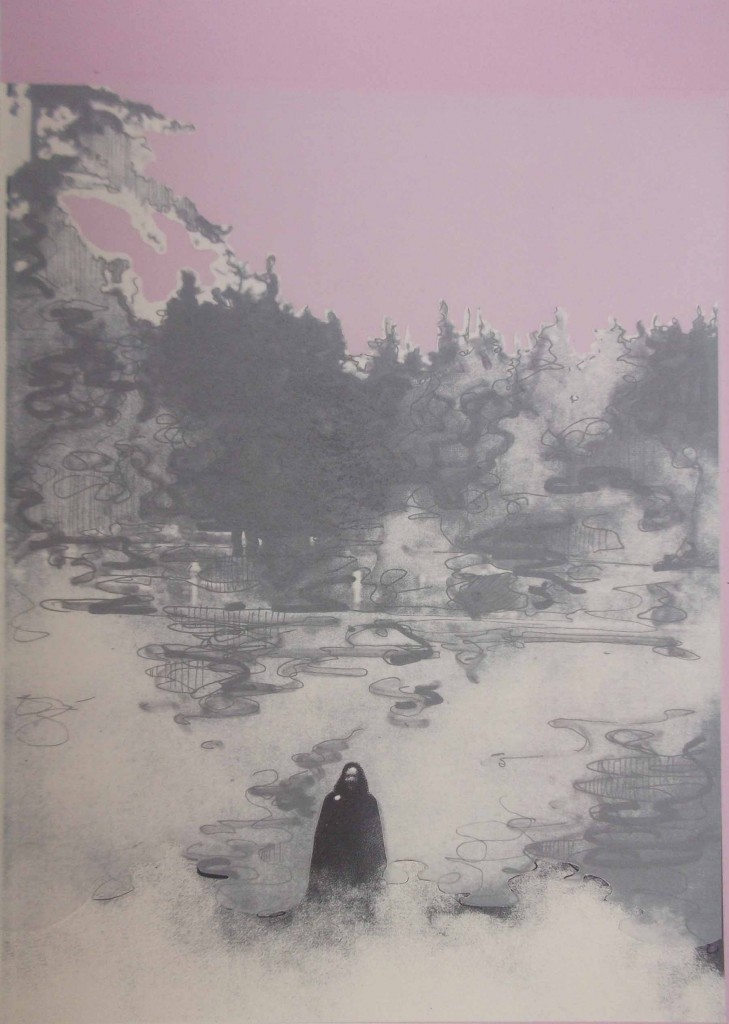

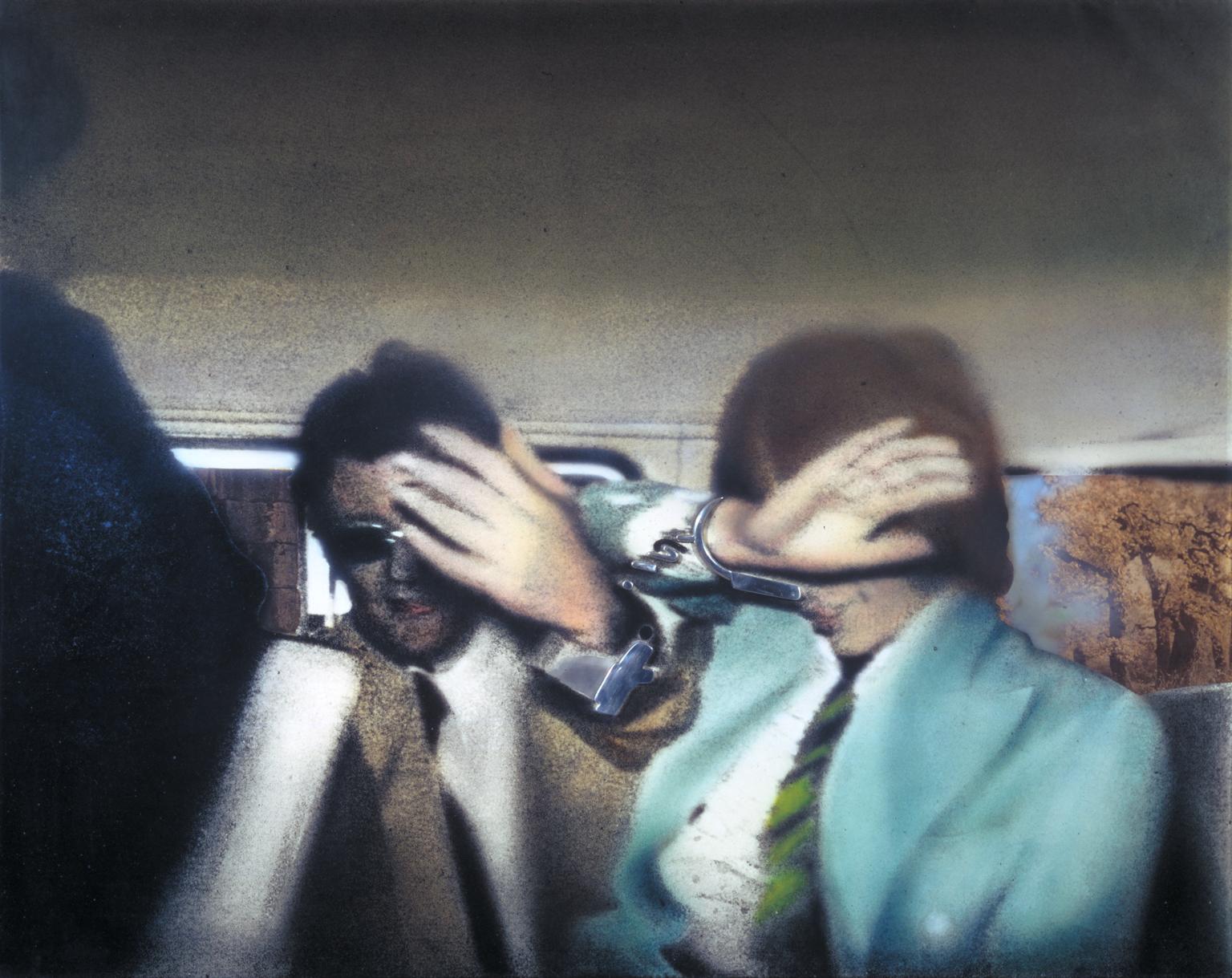

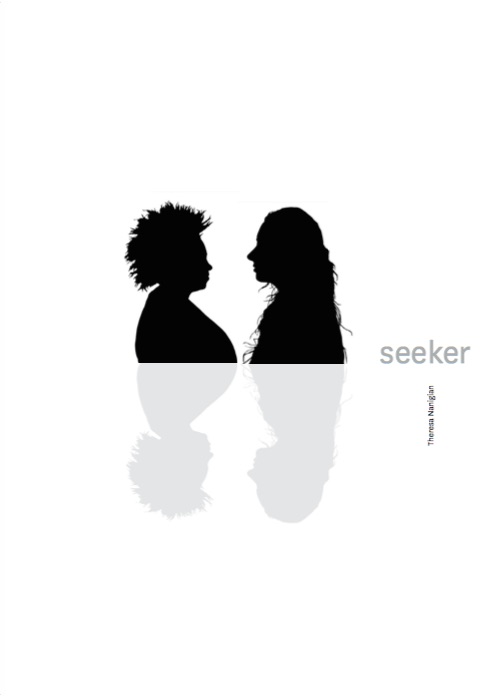

This new film contains motifs and images echoing earlier works by Gaffney. As with those films there is no narrative arc to this one but rather an exploration of duality via two female protagonists[4]. The dynamic between these characters; the way they move and behave reads like a nebulous psychodrama but can also be interpreted as addressing the relationships our species has with the multifaceted entity we name nature.

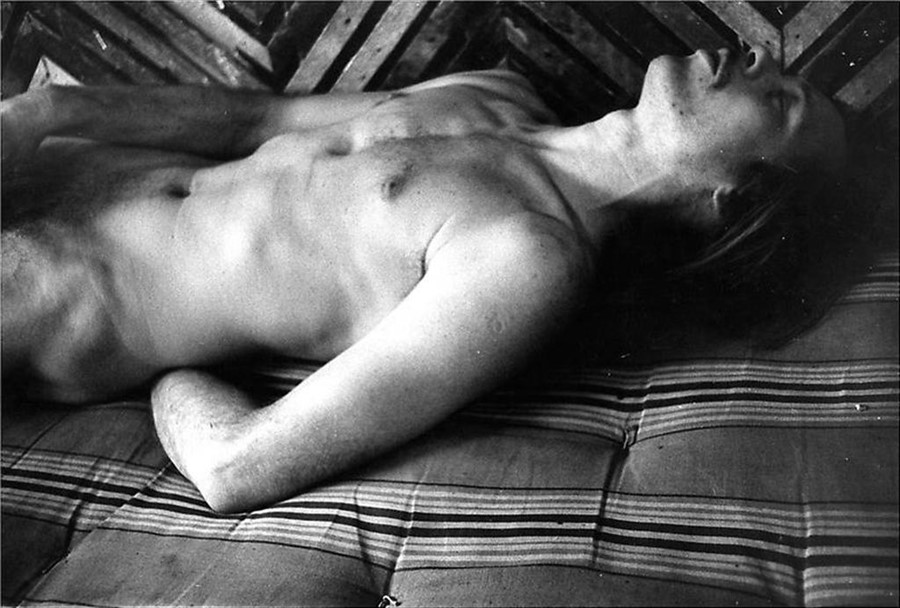

Those familiar with Gaffney’s oeuvre will recognise individuals who have featured prominently in previous work. Helen O’Dea and Sian Ní Mhuirí are the two actors who are central to this film. O’Dea never speaks, yet her physical navigation of the landscape- which she crawls through and collapses in- is expressive. In contrast, Ní Mhuirí’s voice channels various entities; she speaks both as the earth to the more bodily “human” other times she speaks as a person experiencing some sublime revelation.

Fruits of physical exertion

The relationship between Gaffney and the two actors featured here is deeply collaborative; extending from creative aspects to the practicalities and logistics of production. This simpatico dynamic between Gaffney and collaborators lends these films a distinctive character; as all those involved are unified in a semi-structured open ended-process in which the peculiarities of sunlight and atmospheric conditions also play a role.

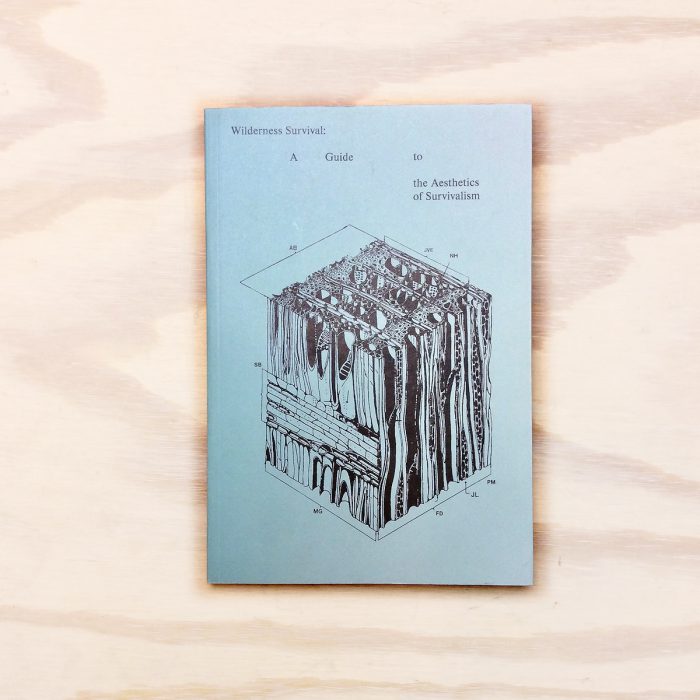

Seductive and highly accomplished in its execution, one would not immediately guess that the film or related images were the fruits of considerable physical exertion or that the scale of the production team was quite as small as it is. The memorable scene of Helen O’Dea submerged in milky fluid was shot on a farm that has been in Gaffney’s family for several generations. The majority of this film was made in Ulster, and Gaffney describes how they and one of the actors “hiked up to Urris Lakes, about three and half hours each way, carrying all the equipment. The aim was to do a ‘leave no trace’ shoot because we didn’t [want to] have a production footprint. I recce’d the location beforehand, so I knew the route and trail, had the weather and sun timings, but we could take our time and figure things out.[5]”.

Outside of language

While the realities of ecological collapse certainly do inform this exhibition, it is not an exhibition ‘about’ this issue per se. Gaffney is not concerned with tackling issues head on but rather with instilling ideas and conveying emotions. Depicting landscape and the physical and sentient entities therein enables Gaffney to communicate emotions and anxieties that lie outside of -or beyond- language. The concept that one might apprehend and communicate one’s own subjectivity via experiences of the natural world that is evident throughout this show is evocative of 19th century Romanticism. In the literature and visual art of the latter movement nature became the vehicle for conveying spiritual and emotional sensation.

Imagery of Romanticism

References to the imagery of Romanticism are especially notable in the still photographs included in this exhibition. This is nowhere more evident than in the in the medium format photograph entitled The pleasure is maybe not mutual which was a particularly dominant feature of iteration of the exhibition at Butler Gallery, Kilkenny. In this striking scene we see Helen O’Dea straddling a mass of rocks; her tresses cover her face and spill over the formation, fusing her with it.

The idea of nature as a sometimes brutal adversary is also repeated in the language and imagery of this exhibition. Gaffney describes how “I was thinking about how climate change wreaks havoc on people’s lives, and it really challenges our sense of control and our own importance. Especially in Ireland, we see nature as very benign, but we need to grapple with the extent of climate change, and the unpredictable and sudden violence of it” [6].

Meanwhile, other elements reveal Gaffney’s own anxieties and their interest in the inherently uncanny -perhaps even sentient- character of the landscape. This is something particularly evident in the medium format photograph A warm mouth swallowing, which looks like a human skull covered in ectoplasm. In Emerging too damp to catch fire, (2024) we see a thistle covered in frothy cuckoo spit. Images such as these highlight Gaffney’s ability to hone in on and study the natural world closely. The process of taking these photographs demanded a slow engagement with the environment. Gaffney likens the process that taking these images entails “to bird watching in that it necessitates great patience and attention to detail […] one must be observant and wholly present”.

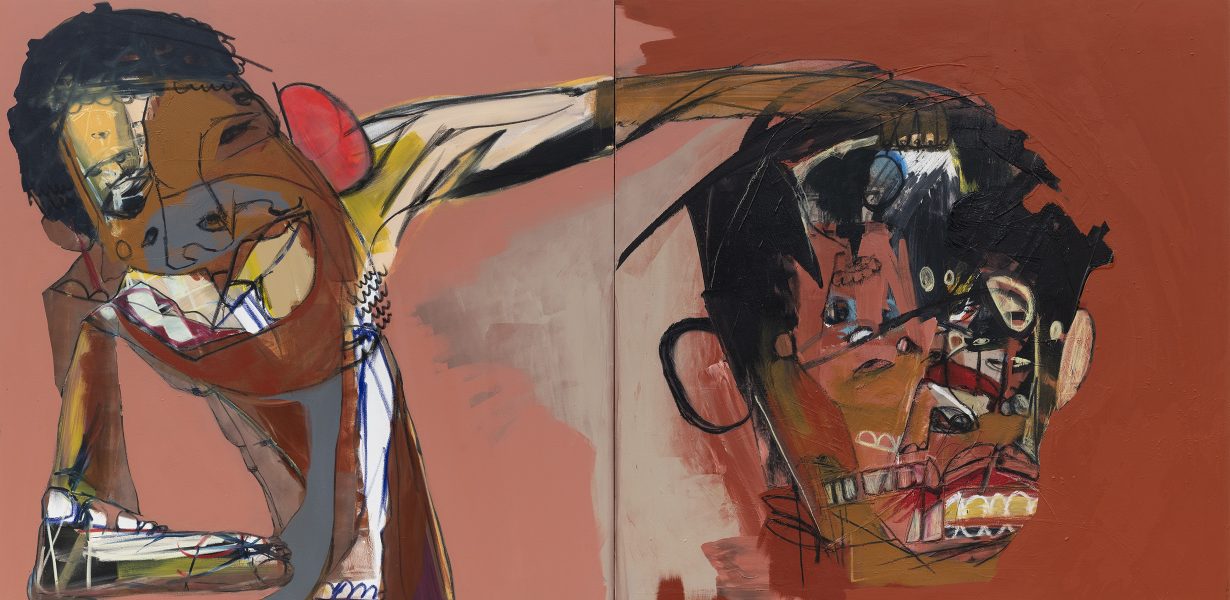

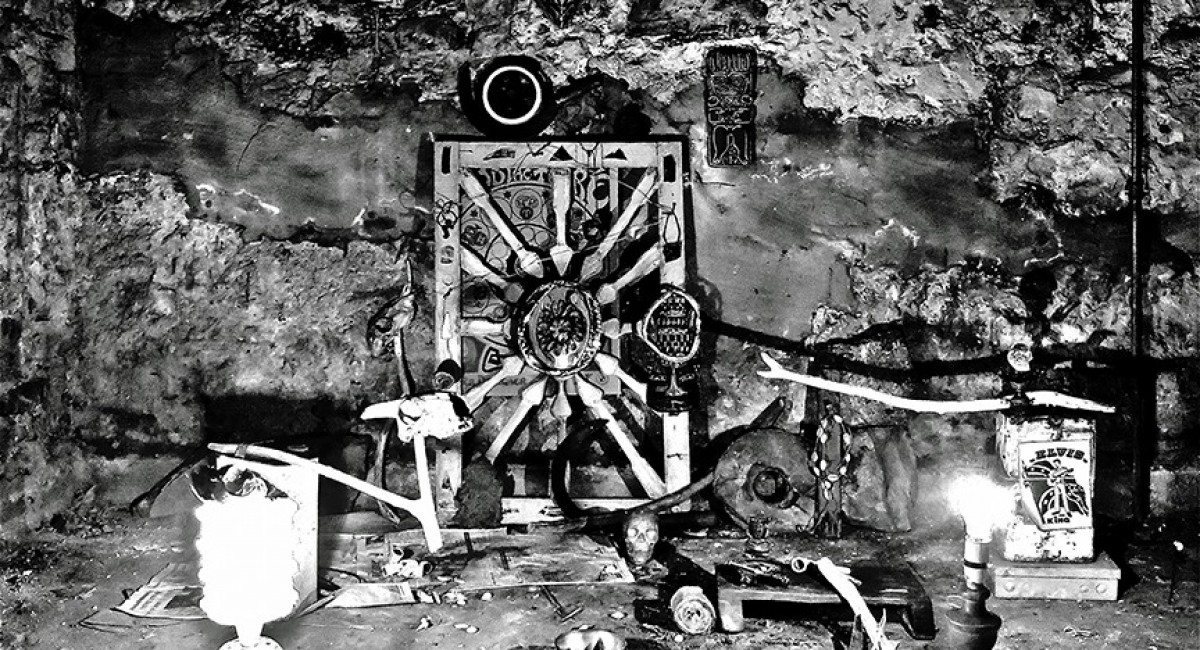

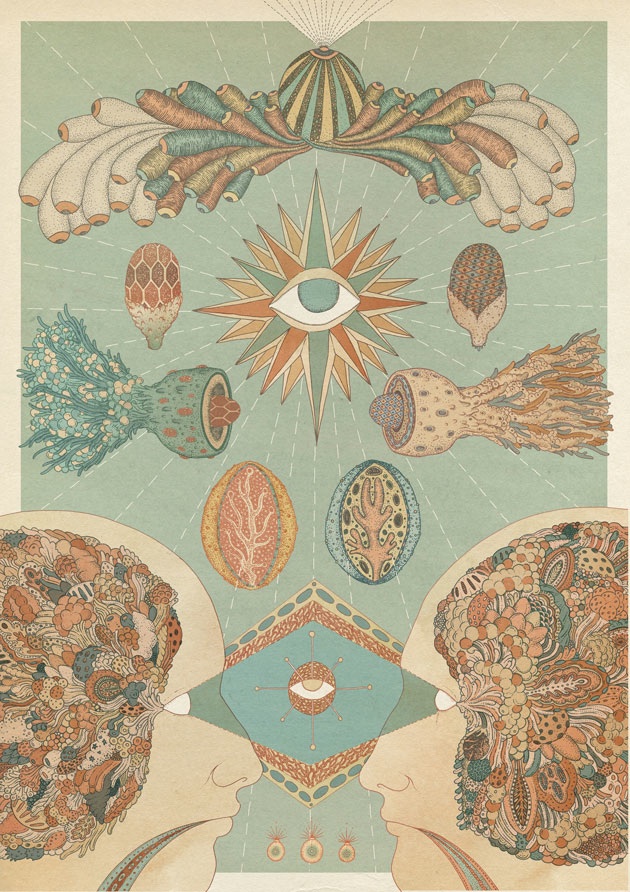

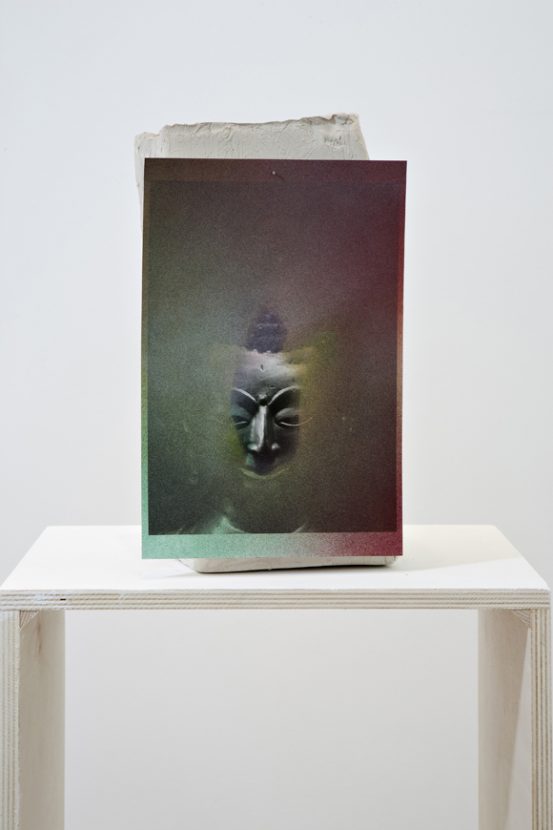

Gaffney draws heavily upon archetypes and creates images that are dreamlike but also mythological in character. This is exemplified in the image of Helen O’Dea submerged in darkness and milky liquid. Gaffney conceived this after discovering a mysterious but ubiquitous plant known as the round-leaved sundew; a carnivorous species that feeds on insects, like a diminutive, native Irish Venus Fly Trap. In 2020 Gaffney began seeking out and locating numerous Drosera rotundifolia in the bogs of Cavan. This elusive plant and its feeding habits significantly shaped the most distinctive visuals in this film.

A distinctly archetypal quality

An enduring aspect of human existence is the contemplation of our tempestuous relationship with the environment. For half a century, an awareness of the destruction inflicted by our species has had a significant influence upon cultural production. It was the 1970s that saw the first wave of art of an ecological bent, much of it informed by positions drawn from feminist and postcolonial studies. More recently, the influence of the philosophical tendency known as new materialism combined with the awareness of climate change have led to a renaissance of art that explicitly addresses climate change. Today, a preoccupation of many artists is how human life is embedded in relationships with various forms of non-human life. Much of the art in the aforementioned vein positions art as a vehicle for research.

Participating in cultural activities in the face of any crisis is inherently complicated. Artists who respond directly to the situation and weave into their work in an attempt to ‘raise awareness’ frequently end up making didactic art that feels futile. Meanwhile, those who don’t engage with the subject at all might be accused of self-indulgence or detached decadence. One of the successes of this exhibition is the fact that it touches upon environmental collapse without recourse to reductive or tokenistic statements. The key to this is the artist’s ability to execute scenes and images that resonate on universal, psychological levels; applicable to the urgencies of the present moment but timeless and wholly Gaffney’s own.

[1] Interview with the artist , Summer 2024

[2] Ibid.

[3] Ibid.

[4] This is also seen in A Numbness in the Mouth (2016). A notable similarity is the image of individuals being submerged in fluid.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Ibid.