Cloon

Cloon is a sparsely populated townland in Wicklow, on Ireland’s East Coast. No signposts demarcate this hilly territory which is transected by the L1011, a meandering byroad connecting Enniskerry to Glencree. In a field high up on the side of a valley, where the invisible county border with Dublin lies, one can see – with considerable effort – a cluster of almost imperceptible depressions and mounds.These undulations are all that remains of The Cloon Project; a complex of earthworks conceived in the late 1970s by artist Brian King (1942–2017).

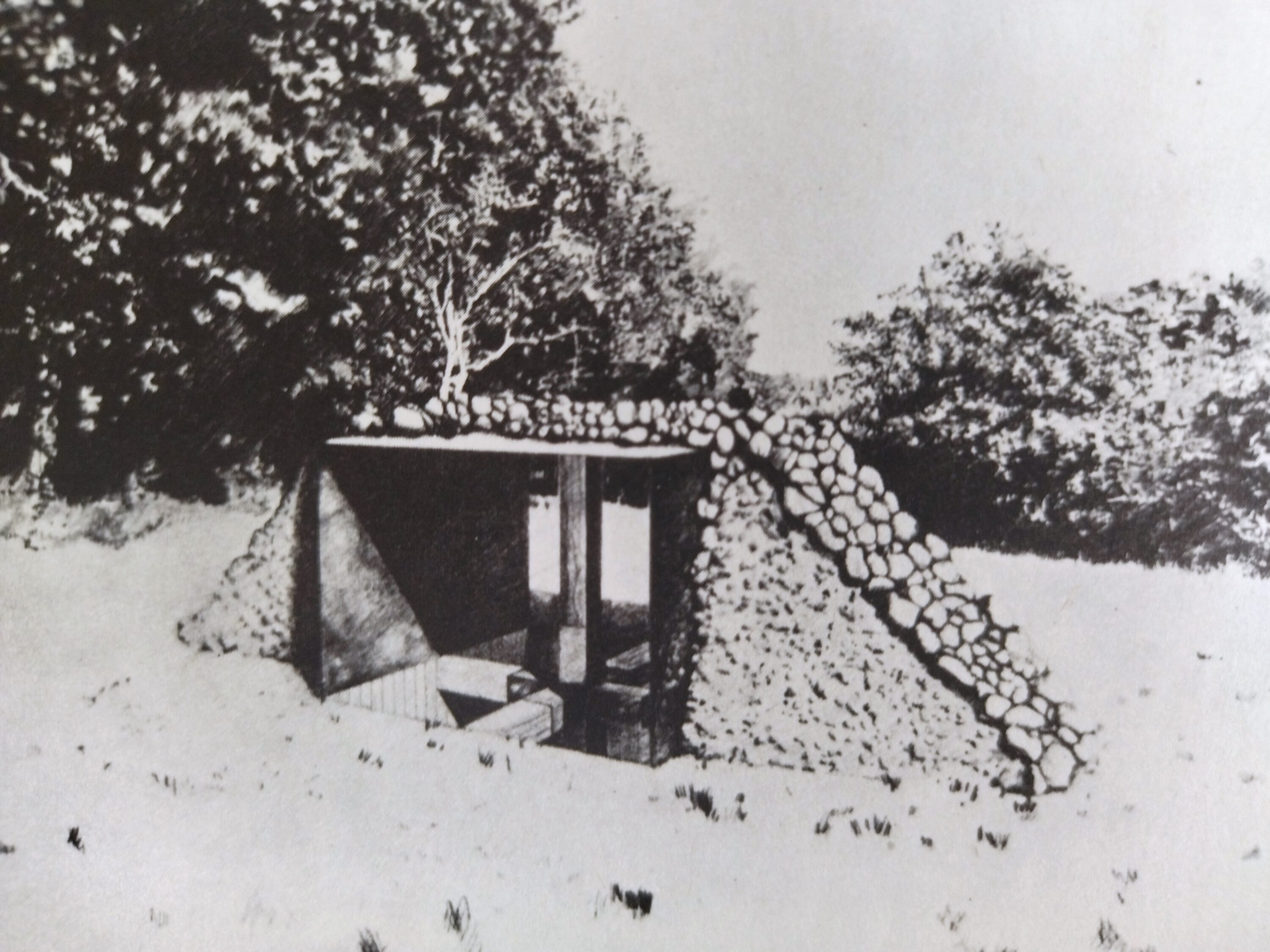

The only extant photo-documentation of Cloon is contained in a 24-page publication that accompanied a solo show of King’s that took place at Dublin’s Project Arts Centre in 1980. Seeing this publication in 2008 is what first drew my attention to Cloon and eventually led me to initiate contact with King. I found the visual qualities of the images in the publication fascinating. While the black and white drawings portray the ideal of how King imagined his interventions would look and function, the photos of the unearthing process evoke an archaeological site or grave exhumation. In an attempt to gain a deeper understanding of King’s work I visited him several times at his home in a south Dublin suburb.We discussed the sculptural language he cultivated in the late ’70s and our shared interest in the megalithic sites of Ireland.

As I learned more about Cloon – and how the project had unravelled – my fascination deepened. During a visit in the autumn of 2009, King explained the extent to which Cloon was ill- fated and had been aborted before it could be completed. Despite high ambitions and clarity of concept, the realities of working with – and in– the Wicklow terrain proved more challenging than predicted.

Cloon is a common place name in Ireland. Its etymology derives from the Irish cluain, meaning meadow or pasture. Some dictionaries give the definition as a ‘dry boundaried area’ which is ironic, since the main problem besetting King’s plan was relentless flooding. Weeks of labour were undone in a few hours of heavy rain, as the deep trenches filled with water and everything turned to mud. Other factors also hindered the project: funds, willpower and capable workers diminished as the winter drew in. By the end of 1980 it had become evident that realising the project would be far more expensive and technically complex than had originally been anticipated. With considerable reluctance – and Sisyphean efforts– it was accepted that the project was no longer tenable. After all the salvageable materials had been extracted, the site was abandoned and, in a few months, the elemental forces had restored it to its former state. By the following spring, grass had begun sprouting from the refilled craters.

On my final visit to King’s home, he showed me a work he had made thirty years previously. It combined stencilled text with black and white images of sea stones he had photographed on nearby Shankill beach. He smoked silver Silk Cut cigarettes throughout the conversation and a Roomba circled blindly around the adjoining room, occasionally bumping into furniture.

It felt like an apposite time to reflect on failure, hubris, and physical disintegration; a febrile atmosphere hung over Ireland, as the magnitude of the fallout from the Great Recession became apparent and the nation moved into a state of suspended ruination. Edifices like the Anglo- Irish Bank HQ and the Elysian Tower (1) stood unfinished or unoccupied and the term ‘ghost estate’ entered common parlance. At the time, there was considerable controversy surrounding the construction of the M3 motorway near the Hill of Tara and the resulting destruction of sites of major archaeological and mythological significance.A not-insignificant number of protesters argued that ‘the curse of Tara’ was at the root of economic meltdown and the related tribulations.

It is worth noting that even if Cloon had been completed as had been planned it would look much as it does today, indistinguishable from the surrounding landscape. For each part of the intervention was conceived to collapse on itself and disappear over time. In a drawing for one work entitled ‘Six Foot Deep’, a deep cavity is sealed by a sheet of steel upon which a mound of gravel and loose stones is then piled. In theory, the sheet would abrade and eventually give way and the cavity would once again be filled. This and the other elements of the project were conceived to be gauges of entropy, evocative of Robert Smithson’s 1970 ‘Partially Buried Woodshed’. ‘Six Foot Deep’ is also redolent of ‘Perimeters/ Pavilions/Decoys’ by Mary Miss; two images of which feature prominently on the second page of Rosalind Krauss’‘Sculpture in the Expanded Field’ which was published in October Magazine in 1979. But other influences also permeated, particularly Irish prehistoric stone structures and more broadly, a preoccupation with death, burial, and bodily internment.

King’s foray into land art was influenced by the cultural context of the late 1970s but it was also shaped by personal circumstances.The project betrays a yearning to go ‘back to nature’ and engage in physical processes of sublimation with the earth; a desire to extricate oneself from the claustrophobia of Dublin and the routines of teaching art (2).

A significant event prompting a shift in King’s work was the unexpected demolition of his studio and the resultant loss of its contents. One bank holiday weekend in 1978 several old stable buildings off Dublin’s Baggot St were covertly razed to make way for an office block. Upon arriving at the site of his former studio, he was met with a pile of rubble in which could be seen large fragments of sculptures. The artist was given no forewarning and lost fifteen years’ worth of documentation, drawings, and a substantial amount of equipment. In the decade leading up to this, King had become known for making modular geometric forms in wood and steel, one of which (dating from 1975) can still be seen on the campus of National University of Ireland in Galway (3). Although traumatic, the catastrophic loss of the studio and its contents was also a liberation, creating a tabula rasa that prompted new beginnings.

The emergence of land art was driven by a desire to place art in dialogue with nature and history (4). Achieving this entailed moving beyond the confines of museums or galleries, then considered moribund and inherently stultifying environments. And yet paradoxically, it was through artworks displayed in such venues and via images in publications that most people became aware of land art.This is certainly the case with Cloon which, although unfinished, was the subject of a family of artworks that ended up in public and private collections. One particularly elaborate piece combines photos, maps and solar charts mapping out the movement of the sun in relation to the earthworks (5). King also produced Cloon a series of elegant pencil drawings; idealistic renderings of how the completed project would appear.The contrast between what is represented in these compositions on paper and what physically occurred is loaded. For here one sees the difference “between the idea and the reality; between the conception and the creation (6)” that all of us grapple with.

In Joel Fisher’s 1987 essay ‘Judgement and Purpose’ he discusses how artworks that are deemed to be failures often end up being more revealing and illuminating than if they had succeeded as originally intended. His words resonate with King’s unrealised venture; particularly the lines “sometimes the failures of big ideas are more impressive than the success of the small ones (7)” and “where failure occurs there is a frontier. It marks the edge of the acceptable or possible, a boundary fraught with possibilities (8)”

Cloon was a singular event in the history of Irish art; an attempt to cultivate a vernacular of land art that chimed with sacred ancient sites.The fact that it was ill-fated does not detract from the importance of the endeavour. It is the disintegration of this undertaking – and its resultant incompleteness – that makes it so tantalising. For this is also a story of nature winning; of an artist’s elusive vision being prematurely entombed in mud. That the ruins of Cloon are imbued with disappointment and dashed expectation only adds further to the mythos of those hard-to-find remnants, buried somewhere up there in the Wicklow hills.

- An IrishTimes article that year described the latter building as a“Mary Celeste”adrift after the recession

- King was head of sculpture at NCAD from 1979 to 2004

- In 1969 King represented Ireland at the Paris Biennale and won an award with one such sculpture

- Lucy Lippard’s 1983 book Overlay expands upon this

- This work is held in the collection of the Irish Museum of Modern Art

- Roughly quoted from T.S. Eliot’s The Hollow Men

- Le Feuvre, L .(ed). (2010) Failure: Documents of Contemporary Art ‘Joel Fisher: Judgement and Purpose’.Whitechapel Gallery and The MIT Press. Page 118

- ibid