I Am So Multiple In Nights

Jungian scholars often describe cellars and basements as symbolising the unperceived scope of the psyche. Both the unconscious and the cellar are dark, subterranean zones where uncanny or alien entities may be encountered. Entering, and encountering these entities is what allows us to face the concealed or dark parts of the psyche: what is often referred to as the “shadow self”. For some psychologists, the dreamer’s navigation of the cave symbolises a desire to regress into the “womb of the earth mother”. This idea is problematised by feminist writer Luce Irigaray, who argues that, rather than escaping the cave (à la Plato’s allegory), we should re-engage with it. For Irigaray, escape means self erasure – a willful forgetting of origins.

In mythologies from all over the world, caves are spaces where life and death, creation and destruction, are simultaneously present. Zeus was born in a cave, while life is also terminated in them, as exemplified by the cavern deities mentioned in the Egyptian Book of the Dead. These chthonic zones are seen as beyond the realm of mortals: gateways to an underworld where communication can be made with supernatural beings. Because of this, subterranean spaces were often used as sites for initiation rites, worship, and divine revelation. The darkness of such spaces, and the fact that they were both physically and metaphorically underground, meant they existed on the fringes of the law. Various cults carried out transgressive Dionysian rituals in subterranean caves: using chanting, music, and substances to summon higher beings and access parts of their consciousness that they could not usually reach.

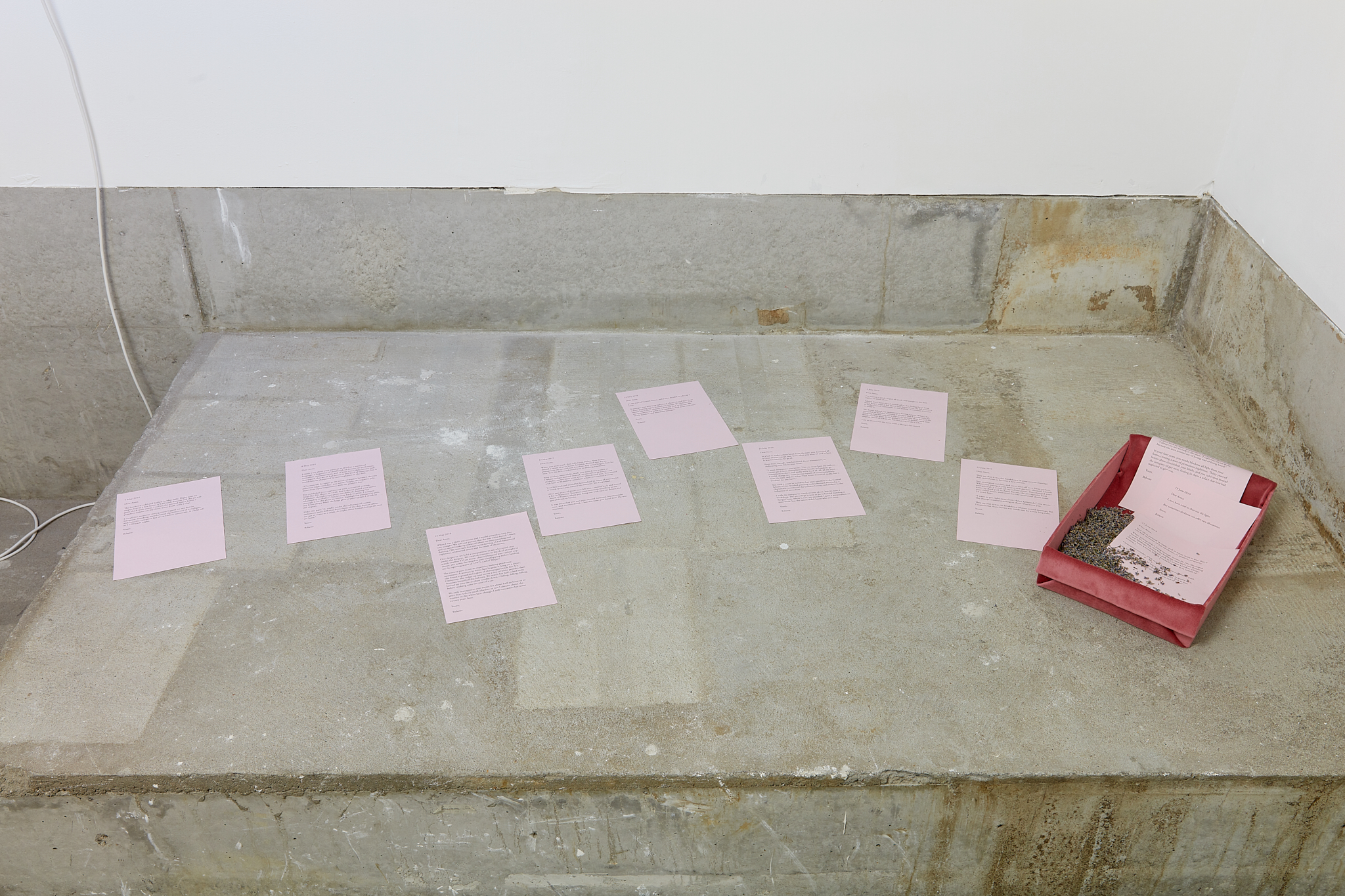

A festive, ritualistic and at-times chaotic quality links these earlier pagan rites with the Young Leo dance parties held in the exhibition’s basement venue over the last year. These nocturnal events, founded by artists who work in or around the building, showed how the most basic of technologies and electronic music can transform a subterranean crypt into a site of convivial togetherness. Over the course of these nights, the basement became an immersive environment for intense experience, calling to mind American anarchist author Hakim Bey’s concept of the ‘TAZ’ (temporary autonomous zone), which describes a short-lived, precarious and liminal zone, in which peak experiences and altered consciousness are realised without any hierarchy. To some extent, this site-responsive exhibition acts as a monument to these gatherings, which, much like the exhibition itself, were founded on a desire for collectively-authored joy .

The exhibition’s title is a translation of words by Emmy Hennings (1885-1948), one of the few women affiliated with the Dada movement, and co-founder of Zürich’s Cabaret Voltaire – undoubtedly the most important nightclub in the history of art. In the case of this exhibition, the title also refers to the idea of the self as a continually evolving and expanding entity, recalling Jung’s belief that the many contains the unity of the one, without losing the possibilities of the many. As he understood it, the self is essentially comprised of multiple facets, some of which were necessarily concealed but permitted to manifest during particularly revelatory or visionary experiences.

The exhibition’s allusions to archetypal symbolism and invocation of rituals underscores a desire to declare visual art’s continued vitality in our increasingly techno-rational society. The sort of utopianism that flourished in the last century, concentrated in sites like the short-lived Cabaret Voltaire, may never flourish again. Nevertheless, the sphere of potential that visual art carves out remains a space in which idealistic intentions and romantic aspirations can still frequently be found: a temporary autonomous zone where we collectively climb back into the cave, and find our multiple selves.

-Pádraic E. Moore