I’m Your Transformer

Gina X Performance \ Nice Mover + Voyeur [TWI 1249 / CD]

Les Disques du Crépuscule presents a new double disc remaster of two seminal albums by German synth wave pioneers Gina X Performance, whose groundbreaking singles Nice Mover, No G.D.M. and Kaddish remain enduring electroclash staples after four decades of club supremacy.

Formed in Cologne in 1978, the core of Gina X Performance composed vocalist Gina Kikoine and producer/keyboard/vocoder wizard Zeus B. Held. ‘I had in mind science fiction-inspired tracks,’ explains Zeus. ‘Really cold sounding music, with no blues-et chords or melodies, no guitar and nothing rocky.’

Originally issued on German imprint Crystal 1979, icy, noirish debut album Nice Mover spawned two radical Eurodisco hits, with gender-bending single No G.D.M. becoming a firm favourite at the legendary Blitz Club in London’s Soho. At the same time Zeus B. Held also became an in-demand producer, working with John Foxx, Fashion, Rockets and Dead or Alive.

The third GXP long player, Voyeur, from 1981, followed a brief spell on EMI and saw the duo return to their experimental, avant-gardist roots, the material by turns seductive, provocative and confrontational. Since then countless electronic artists have acknowledged or betrayed the influence of Gina X Performance, including Depeche Mode, Propaganda, Ladytron and Peaches.

Remastered in 2021 by Zeus B. Held and Lars Lafayette Fassbender, the 2xCD set is housed in a 6 panel digipack sleeve with new artwork and a 12 page booklet featuring archive images and essays by Pádraic E. Moore and Princess Julia. The 8 bonus tracks on the CD format include remixes by DJ Hell, Headman, Red Axes, Psychonauts and Zeus B. Held.

I’M YOUR TRANSFORMER

Gina X Performance formed in 1978 with the aim of making sophisticated, decadent music in the spirit of movements such as Dada and Fluxus. The talents of front person Gina Kikoine and varying accompanying line-up were marshalled into a cohesive composite by musician-producer Zeus B. Held. Emulating disco’s ecstatic exuberance, GXP’s music has occasionally echoed the provocations of punk, though their sound is more seductive than confrontational. Held’s innovative use of then novel instruments (e.g. Sennheiser Vocoder and ARP Sequencer) created a dramatic backdrop for Kikoine, whose literary lyrics are sung and spoken in guttural English and German. Their sound defies definition and cannot be neatly fitted into any one genre but a suitable description might be Dionysian synth-noir.

Cologne in the late 1970s was a hive of cosmopolitan activity, vivified by an experimental film scene and a coterie affiliated with Stockhausen’s Studio for Electronic Music. But it was particularly renowned as a hotbed of visual art, with exhibitions by international artists taking place frequently at public institutions and commercial galleries. Glimpses into this cultural landscape are woven into Kikoine’s lyrics via references to artists whose contribution she deems particularly pertinent. In “Video Voyeur”, the pioneering multimedia artist Nam June Paik is celebrated. A major exhibition by Paik took place at the Kolnischer Kunstverein in 1976 that included ‘Zen for TV’, one of his most seminal pieces, the title of which Kikoine refers to specifically. But the artist who had the most significant impact on Kikoine was undoubtedly Andy Warhol, who is alluded to directly in “Tropical Comic Strip” via the confected image of a “Campbell’s Soup Swimming Pool”. Warhol’s iconography fascinated Kikoine; his silk-screened portrait of leather-clad Marlon Brando; the polaroids of drag queens and trans women. Perhaps even more important was the disinterested, vacant public persona that Warhol contrived. When in 1963 he stated “I want to be a machine” he was referring to his use of mechanical reproduction in printmaking. Yet this statement presaged the character Warhol constructed, which resounded with a myriad of recording artists in the late ‘70s and early ‘80s who -like Kikoine- affected a detached, automaton-like delivery.

GXP’s output is multifaceted and may be experienced viscerally, via the body, (preferably through a powerful sound system in a subterranean club) but also on a cerebral level. Kikoine’s intertextual lyrics contain a profusion of evocative images and complex word play that is only revealed upon repeated listening. The line “I’m your Transformer” that opens “Nice Mover” evokes the double meaning at play in the title of Lou Reed’s 1972 album. The transformer in both instances refers to an electrical device that transfers energy and an individual whose identity is subject to change; who is both Marlene and Gino. Gender fluidity is a motif that runs throughout Nice Mover, with Kikoine’s desire to “be a swinging boy” slightly predating Bowie’s ironic “Boys Keep Swinging” on Lodger. The idealised male who is the subject of this song wants to resemble James Dean, a star whose allure is amplified by his own sexual ambiguity and premature death.

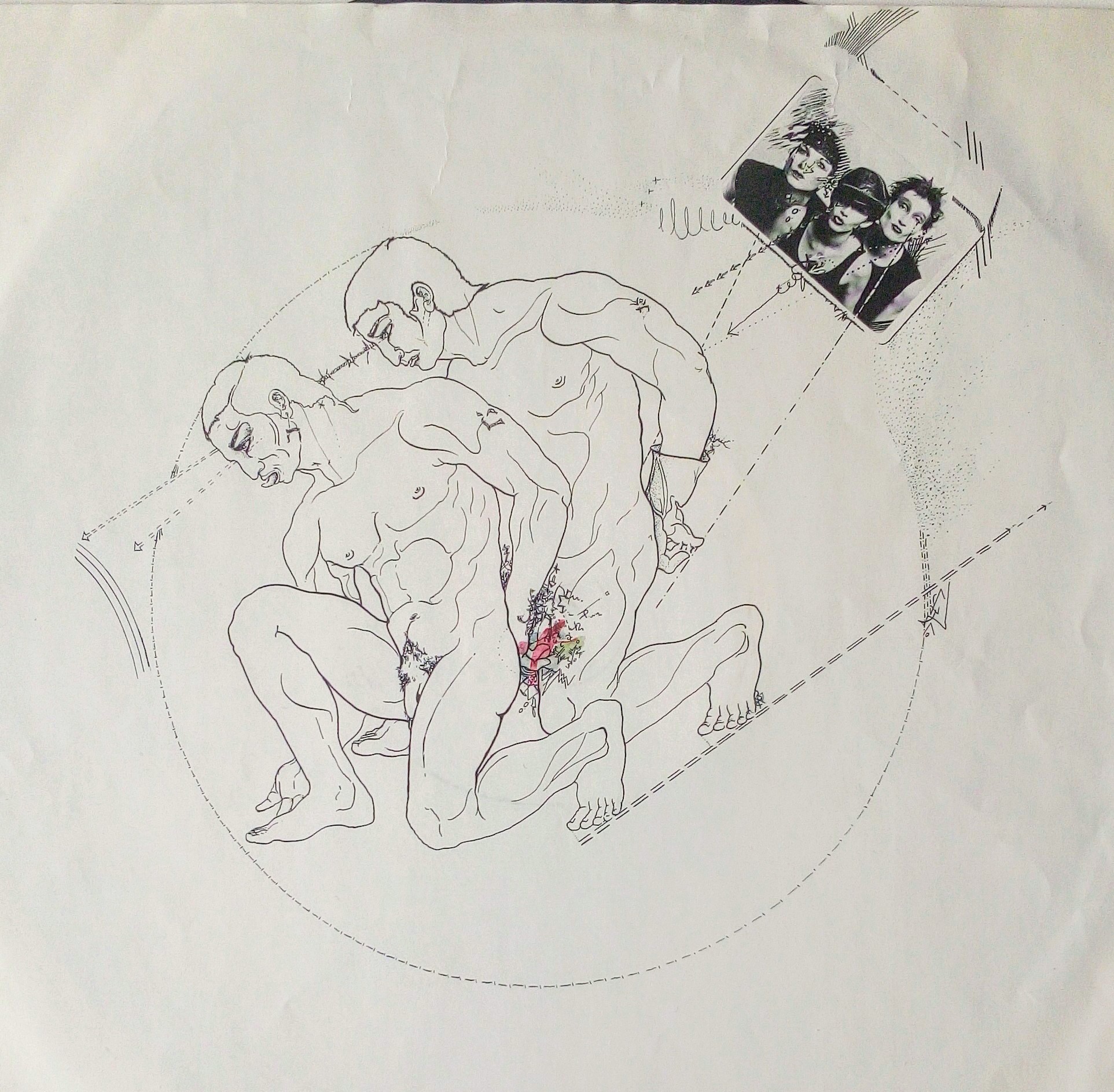

If the dominant motif of Nice Mover is a metamorphosis from female to male, then homoerotic desire is a chief theme of Voyeur. This is demonstrated most explicitly in “Hom Intern” : an imagistic exploration of the semiotics of handkerchief colour codes. The term Homintern is a play on the term Comintern (Communist International) and was coined in the mid-twentieth century to refer to a supposed conspiracy of deviant ‘homosexual elites’ allegedly controlling the world of culture, what might also be described as the gay mafia. Allusions to non-heterosexual desire are frequent in the realm of GXP but Hom Intern exemplifies Kikoine’s penchant for alluding to outré sexual trysts. This must be one of the only tracks in the history of recorded music to feature such flagrant references to fisting? Elsewhere on Voyeur acts of a more extreme nature are described. In “Hypnose” sensual pulsating rhythms carry Kikoine’s explicative descriptions of a BDSM session that climaxes with a circumcision. MAF Räderscheidt’s elegant line drawing on the sleeve ostensibly depicts ‘Greek Love’ but could also be some form of ritualised surgery, as suggested by the presence of a rubber glove.

Perspicacious GXP fans will note that one of the sculptural figures in the aforementioned album art wears an earring made from the Hebrew word Chai, meaning life. This a visual link to “Kaddish” undoubtedly one of the most rapturous and transcendent tracks in the GXP opus. Detailing Jewish mourning rituals, the distorted voice of Kikoine imperiously outlines observances of the funeral service; the covering of mirrors and the bereaved sitting upon low stools. Each GXP album is a web of arcana and Kaddish typifies their proclivity for esoteric subjects. This tendency towards relatively obscure material contributes to the mystique surrounding GXP. As does the fact that even in this age of internet saturation, very little information relating to the band is available. This elusiveness ensures the group remains shrouded in enigma, a source of infinite speculation.

GXP’s appeal is enduring and each decade brings a fresh swell of new interest. The first significant wave of enthusiasm and reevaluation occurred in the early to mid ‘00s; a period in which many recording artists were producing music that was heavily influenced by early ‘80s electronica. At that same moment there was a widespread rediscovery and recuperation of music that had been overlooked when it was originally released. LTM’s reissuing of the four GXP albums in 2004 contributed greatly to a resurrection of their music. Similarly, the inclusion of tracks such as No GDM and Kaddish on several compilations released at the time (such as that associated with London’s Nag Nag Nag club) contributed to these tracks becoming anthems for then burgeoning subcultures. More recently Kikoine and Held were awarded the 2020 Holger Czukay Prize for Pop Music from the City of Cologne for outstanding contributions to the city’s musical history.

There are a constellation of reasons why GXP’s legacy continues to attract legions of cultish fans. Empowering is the idea promulgated repeatedly in Kikoine’s lyrics that one’s identity is a work-in-progress; something perpetually evolving that can be altered at will. This is of course the central tenet of No GDM, which is dedicated to Quentin Crisp, the self-proclaimed stately homo. Crisp could be considered an heir apparent to Oscar Wilde, whose philosophies are an important touchstone in GXP’s queer canon. Ultimately, the music of GXP is a call to arms for all those who, for whatever reason, are “feeling different to the rest of the herd”. Expanding on the ideals of Wilde, Kikoine asserts that artifice, dandyism and decadence should not be viewed merely as aesthetic principles but embraced wholeheartedly as vital strategies for living.