Inner Content / Outer Shape: The Work of Aleana Egan

In autumn of 2009, Aleana Egan and I collaborated on a solo show of her work at Dublin’s Temple Bar Gallery. The project felt particularly significant for us both; it was her first solo exhibition in Ireland, having been out of the country for several years and one of my early forays as an independent curator. The exhibition had a stark skeletal feel in comparison to the work she has produced in more recent years. All the pieces were made whilst Egan was living in Berlin, and they were unified by a palette that evoked a Berlin winter: whites, blacks, leaden greys. Looking back on that exhibition, entitled Sunday Night, one can see in embryonic form many of the characteristics that are now so pronounced in Egan’s work. In the years that have passed since then, Egan and I have established a close friendship punctuated by occasional collaborations. These endeavours are informed by a shared sensibility shaped in no small way by the experience of growing-up and being schooled in Dún Laoghaire, the coastal suburb of Dublin. Over the years we have discussed her work on countless occasions; via studio visits or trips to view artworks installed in various locations. In this time, I’ve come to recognise that an intuitive investigation of materials is the essential impetus for Egan’s work. This is coupled with a compulsion to devise a formal vocabulary that evokes, what Clive Bell described in his book Art (1914) as ‘aesthetic emotion’.

When I first became properly acquainted with Egan’s work in 2004, she was particularly interested in the writings of psychoanalyst D.W. Winnicott. In his work, human beings ‘find themselves’ only in relation to others, and independence is gained through acknowledgement of dependence upon others. Another precondition of health according to Winnicott is the capacity to surprise oneself.

At the centre of each person, is an incommunicado element, and this is sacred and most worthy of preservation.

-D.W. Winnicott, Communicating and Not Communicating, 1963

More recently, Egan has looked to the psychoanalytical and aesthetic theories of Marion Milner (1900–1998). In particular, Milner’s diary-form books, whose genesis was working with what she called her ‘own material’. This was a process that began with Milner identifying experiences she felt were significant and designating them as ‘bead memories’. These ‘beads’ then became a focus for prolonged reflection and over time Milner would attach to them material she felt resonated with the original emotional impulse in some way. This material usually consisted of excerpts of literature gleaned from diverse sources, such as mythology, religion and fiction. This process simultaneously facilitated forms of self-analysis and literary experimentation, the latter of which fed into the production of an intertextual composite. According to Milner, this process enabled her to obtain a deeper understanding of what she described as the “mysterious and astonishing fact of simply being alive”. Both Milner and Winnicott were interested in giving a picture of nurturing ways for us to be sociable – a life of exchange through inter- personal relationships.

Thus, it was that I began a task which has absorbed my efforts for many years: trying to manage my life, not according to tradition, or authority, or rational theory, but by experiment.

-Marion Milner (Joanna Field), A Life of One’s Own, 1934

In recent years, Egan has implemented analogous methods in the develop- ment of sculptural entities. The initial mode opératoire employed, is that of a bricoleur: literary fragments – but also images, forms and colours – are accumulated in the form of notes, drawings and photos. These accumulations are then refined, manipulated, translated – and often completely altered – via manual techniques in the studio. The resulting composites are essentially armatures onto which webs of personal memories, intensely felt emotions and half-formed feelings are then embedded. The preliminary process outlined above can be seen in the works Egan produces on paper – in particular the collages combining drawings and photos. The approach is also exemplified in a postcard Egan was commissioned to design for a project celebrating the centenary of Iris Murdoch’s birth. This postcard brings together the three main strands of Egan’s practice (sculpture, drawing and photography) and demonstrates how there is frequently a drift between them, to the extent that they are occasionally combined and subjected to processes of translation.

Let us consider each of the elements of this postcard: an image of one of Egan’s wall-mounted sculptures; drawings of arabesques in blue ink and a photo of an urban vista, which I have been informed is Athens. The arabesques demonstrate Egan’s preoccupation with outline and underscore how drawing is a crucial starting point for much of her work. The photo also highlights Egan’s penchant for diaristically documenting her environment and her enduring interest in architecture, in particular facades. This fascination with architectural exteriors has remained consistent – forms gleaned from a facade, lines taken from the wrought iron work of a balcony or the peculiar shape of a window are photographed or drawn. Balconies in particular are a subject of aesthetic interest for Egan, and she has photographed them in numerous locations over the years. She remarks that in addition to “being architectural forms, balconies are also invitations to imagine the inhabitants of the building in question.” Egan’s proclivity for imagining the characters that might inhabit particular dwellings is long-standing and can be seen in numerous works, such as a collage from 2008 entitled Interactions. Yet it is not only architectural exteriors that fascinate, Egan looks also to other outward-facing structures and surfaces – the silhouettes/shapes of items of clothing also frequently provide a focus.

That Egan would be involved in a project celebrating Iris Murdoch is apposite. For the writing of the Irish/British author has long been a touchstone for Egan, as demonstrated by her use of phrases sourced from Murdoch’s books as titles for her works. It is instructive to look at some of the other literary figures Egan has drawn upon over the years: Elizabeth Bowen, Jane Bowles, Mary Butts, Marguerite Duras, Jean Rhys and Virginia Woolf. While these are a diverse and stylistically different set of writers, they share a number of commonalities, perhaps most obviously a consideration of how literature can be used to reflect and indeed form female subjectivity. For Egan the act of reading is an inherently generative process. The fragments of sentences, the essence of a particular character, images conjured by a narrative or even the structure of a phrase or pairing of words can provide a catalyst. An engagement with literature and the speculative space this allows access to permits an exploration inward – a meditation upon one’s own emotional state. Perhaps allowing what Marguerite Duras describes asa ‘deciphering [of] what is already there’.

As mentioned, Egan’s methodology frequently entails a repeated and obsessive investigation of a particular motif or shape, whereby it is drawn or manually formed so that it becomes imbued with a constellation of personal associations. In drawings and sculptures alike, this process results in a vocabulary that possesses figurative aspects while remaining firmly in the non-representational realm. Knots of emotion-laden memories and unresolved larval impulses are summoned from the unconscious and used as ‘raw materials’ that are implanted into a chosen medium. This is essentially a form of sublimation, whereby a subjective set of references are translated into a particular material, rendered in symbolic forms that occasionally resonate with art historical precedents. What informs or shapes a given work usually remains oblique. This points to primacy of process – manual actions are charged with a spontaneous jouissance. In addition to the process of aggregation, manual manipulation and material experimentation are funda- mental strategies in Egan’s studio practice.

In the formation of artworks, Egan frequently draws upon emotions elicited by lived-experiences or personal relationships. A photo used for the invitation of a recent solo exhibition at Konrad Fischer featuring a decaying Isuzu Trooper at a scenic location was taken on the grounds of her father’s house in the Dublin mountains. This is one of many photos Egan has taken at this location and recalls a series entitled Green Car (taken almost 15 years earlier) that depicts her father posed beside a green Citroën 2cv.

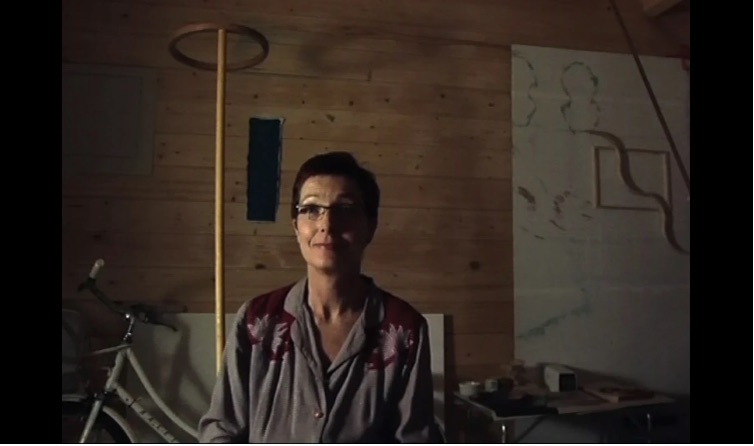

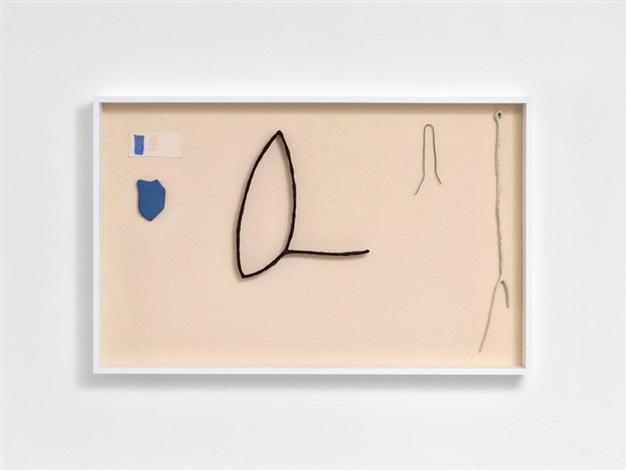

In Helen, a video from 2008, Egan films her mother sitting in a carefully orchestrated interior that includes a number of sculptural objects, reading excerpts from The Red and the Green (1965) by Iris Murdoch aloud to the camera. Stills from this video evoke the paintings made in the 1890s by Edouard Vuillard depicting his mother quietly reading in domestic interiors. These visual affinities are no coincidence, for the work of Vuillard – and that of his compeer Pierre Bonnard – have been an important influence upon Egan for several years. At the end of the 19th century, Bonnard and Vuillard came to be known as proponents of ‘Intimism’, a subgenre of Post-Impressionism focusing predominantly upon psychologically charged paintings of friends or family members in interiors. While the Intimism of Vuillard and Bonnard is essentially figurative, it is distinguished by the inclusion of pictorial elements that constitute a form of nascent abstraction. This is most evident in the patterned, textured treatment of fabrics, wallpapers and other interior furnishings. Rather than aiming for accurate representation, Intimists used shape and colour to convey atmosphere and emotional intensity. In a more recent work by Egan entitled bead (the avenue) from 2019, an appreciation of Vuillard is particularly apparent. One of the elements in this work, a leaf-shaped form made from plaster and painted a deep blue, is a direct interpretation of a shape found in a Vuillard print from 1899 entitled The Avenue.

Although primarily used to refer to the historically specific group of aforementioned artists and their near contemporaries, the term Intimism can also be applied to contemporary artists, who produce works of an introspective, reflective nature, concerned with the intensity of emotional exchanges. Previous writing has emphasised comparisons between Egan’s work and that of post-minimal artists with which there certainly are resonances. However, considering Egan’s emphasis on ‘emotional content’, human relations and subjectivity she might equally be described as an Intimist. Considering her work in this way, we might better recognise within it the structures of feeling and emotional states that Egan is seeking to convey. In early 2020, I visited Egan’s solo exhibition at Konrad Fischer Galerie in Dusseldorf. Although I’d visited the gallery twice previously, this was the first time I’d been there during the day, when the surrounding buildings were clearly visible from the upper floors of the gallery. Looking out from the rooms where Egan’s works were displayed, one could see the apartment block that stands opposite the gallery with its rows of balconies. On each balcony could be seen stuff of daily domestic life arranged in ways that subtly revealed details about the habits and personalities of the inhabitants: washing lines upon which clothes were hung out to dry, folded-up chairs, crates of empty beer bottles. Viewing these quotidian details in the light of Egan’s work felt apposite, for she has always been drawn to the ways people display their idiosyncrasies in unselfconscious, outward ways. Indeed, Egan’s works can be viewed as ‘sculptural responses’ to the minutiae that makes up life. These idiosyncratic ‘responses’ emerge out of a need to negotiate and interpret what it means to live in the world.