MEMORABILIA

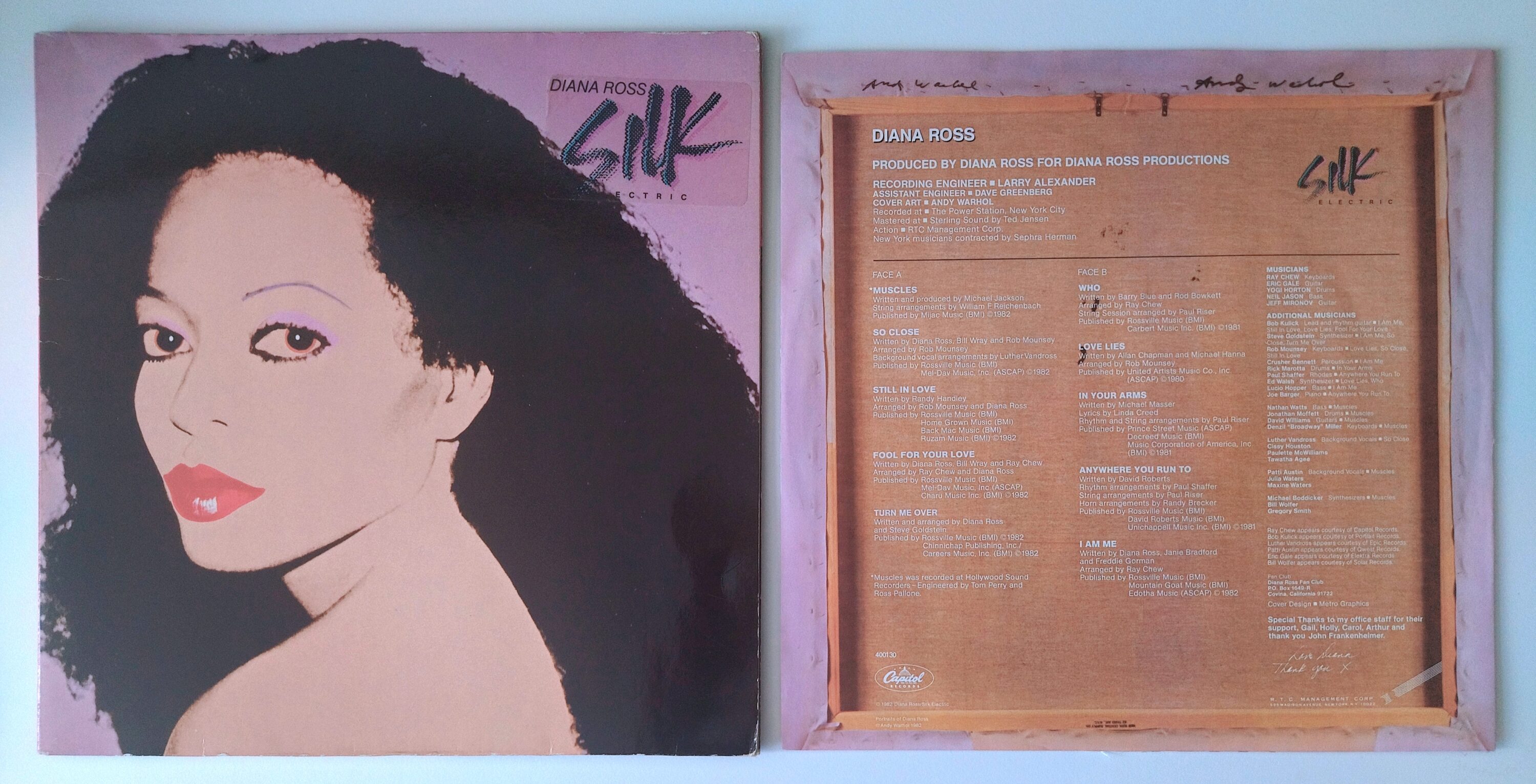

Last March I bought the 7-inch single of Muscles by Diana Ross for one euro at a Brussels flea market. The splendent Warhol sleeve stood out amidst the hundreds of singles piled carelessly into a dusty plastic box on the pavement. There is no text or title on this sleeve, but the artist – and the distinctive way its portrayed – are instantly recognisable. Ross’ face looks as though it is illuminated by a flashbulb that reflects in her glossy cherry-red lipstick. This image is a detail of a larger portrait that Warhol was commissioned to produce for Silk Electric, the 1982 album from which Muscles is taken [1] . The gatefold sleeve of this LP is sumptuous, opening out to reveal Ross in front of coral, fuchsia, magenta and rose backdrops, wearing different shades of lipstick. The inner sleeve containing the LP consists of a photo of the back of the canvas on the back of the portrait, which has been signed twice by Warhol; a self-reflexive touch.

There is a copy of the Muscles 7-inch held in the MoMA collection that is almost identical to the one I acquired at the flea market. [2] The divergent lives of these objects – one circulating as disposable flotsam and the other archived in controlled conditions (object number 854.2013.329) exemplifies the uniqueness of Warhol’s oeuvre and how it is incomparable with that of any other twentieth century artist; unanchored to a finite number of artworks. Warhol’s opus is a cultural phenomenon in which traditional distinctions between unique and mass-produced objects are obfuscated. Warhol’s ability to create stylistically innovative images that flowed through the conduits of mass culture was integral to his expansionist strategy of constantly seeking out and creating new markets. If he was a mirror to his age then Warhol certainly reflected the intense neoliberalism and financialisation of the late 1970s while presaging the entrepreneur as a creative maverick that flourishes in our contemporary digital age more than ever.

By the time Ross released Muscles her status as gay icon was firmly established; a mantle cemented by the release of her 1980 hit I’m Coming Out. Written and produced by Michael Jackson – who also sings backing vocals on the track, Muscles is one of many sensual hits from this era which although not written exclusively for a gay male listenership certainly proved particularly popular amongst that cohort.[3] The object of desire in Muscles is a hypermasculine beefcake; Ross sings; I don’t care if he’s young or old, just make him beautiful. I just want some strong man to hold on to, I want muscles. All over his body. In the video Ross is entangled by a phalanx of bodybuilders; each wears only tight briefs and flexes his biceps for the camera. Both the song and video exemplify what Susan Sontag describes as “camp which knows itself to be camp [4]” and there is an aestheticised and mannered quality to the whole production.

Sontag’s 1964 essay Notes on Camp (from which that previous quote was taken) can be read as an illuminating counterpart to Warhol’s entire oeuvre. For much of what Sontag details as defining a ‘camp sensibility’ corresponds neatly with the aesthetic Warhol cultivated and the subjects he was drawn to. Warhol’s “love of the unnatural: of artifice and exaggeration[5]” is undoubtedly one of the factors that led him to attempting to create a robot likeness of himself. This episode took place in 1982 (the same year Muscles came out) and was the outcome of a conversation between Warhol and AVG Technologies; a company known for designing interactive product displays and special effects for theme parks and movies. The plan was that the robot (known as the A2W2) would be the centrepiece of a multimedia road show titled Andy Warhol’s Overexposed: A No-Man Show that would be co-produced by Warhol and tour venues across the U.S. This roadshow never came to fruition but the fact that it was conceived highlights the extent of the Warhol corporation’s appetite to constantly expand into new commercial territories.

The existence of A2W2 was touched upon in some of the recent media coverage surrounding the release of the epically long Netflix docuseries The Andy Warhol Diaries in which artificial intelligence is used to recreate the voice of the artist. Each installment opens with the statement: “Andy’s voice in this series is recreated using an AI program with The Andy Warhol Foundation’s permission.” Following this introduction, each chapter follows a similar format, whereby AI Andy reads excerpts from the diary that ‘real’ Andy dictated to writer and confidante Pat Hackett. The combination of unrequited longing, quotidian minutiae and often genuinely profound insights are interpolated with talking heads sharing subjective reflections or historical analysis. The Netflix series is one of two major TV miniseries to have been released this year. While The Andy Warhol Diaries shed light on Warhol’s personal life and love affairs the BBC produced Warhol’s America sought to situate the American artist’s work within the history of Western Art. This three hour long documentary (in three parts) framed Warhol as a history painter who in his Death and Disaster paintings chronicled significant events of the US in the postwar era, such as the assassination of JFK and the Race Riots.

While a fascination with Warhol is constant it intensifies in perennial waves. This current revival of interest and nostalgia – is manifest in part by these aforementioned documentaries – is comparable to that of the mid-to-late 90s, which was fuelled by several depictions of Warhol in cinema. 1996 saw the release of I Shot Andy Warhol, directed by Mary Harron and Basquiat, directed by Julian Schnabel, in which David Bowie played Warhol. I saw these films soon after they were released and both offered alluring insights into a variety of cultural phenomena that were alien to me at the time. Such glimpses undoubtedly shaped my creative development. Even more formative was the experience of visiting the major Warhol retrospective that took place at IMMA Dublin in 1997, the title of which was After the Party. My exposure to Warhol’s weltanschauung was a revelation, both in terms of my intellectual growth and my nascent sense of self. Like any 15 year old, I was actively assembling fragments from the surrounding cultural landscape as a means of constituting my own identity. I was drawn then – as I am now – to Warhol’s cosmos and the inherent queerness of his vision.

I was introduced to – and became a fan of – the Velvet Underground the year before visiting After the Party at IMMA. On my bedroom wall I had a poster I’d bought at the Virgin Megastore; a scaled-up version of the banana Warhol designed for their debut 1967 album. Buying music in the late 90s was comparatively expensive and the absence of anything like Wikipedia meant that the full details of a recording artist’s back catalogue wasn’t readily accessible. The process of finding music – both new and old – was imbued with a sense of discovery. Several of my friends and I owned The Best of Lou Reed & The Velvet Underground; a CD compilation that came out in the mid 90s with ersatz Warhol art on the cover. Their music appealed to me as a teenager because it chimed with the errant existence I was trying to pursue at the time. In the decades that have passed since then the significance of their music has only deepened for me. Now it is inlaid with memories of loved ones and parts of myself that don’t exist anymore.

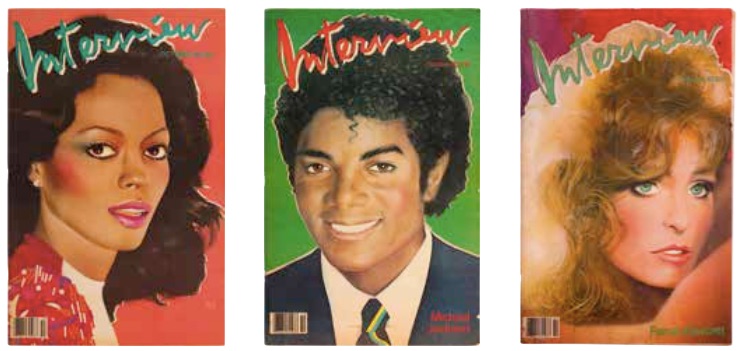

In 2021, I started collecting copies of Interview Magazine, purchasing them from The issues that interest me most are those dating from the mid 1970s to the mid 1980s, which sell for anywhere between 15 and 150 euros. Each is an encapsulation of the pop cultural vista of the month in which it was published; a potpourri of celebrity gossip, interviews, reviews and advertisements. The dazzling covers synonymous with the magazine in this phase are the work of artist Richard Bernstein. Warhol – who co-founded the magazine – invited Bernstein to work at Interview in 1972 and he remained there for the next 17 years, designing almost every cover image in that period.

Many of those who Bernstein glamourised for the cover of Interview also sat for portraits by Warhol around the same time. In the final decades of the last century the status of printed magazines remained undiminished and the reach and popularity of Interview served as a promotional tool that helped Warhol secure further commissions from prospective sitters.

By the mid 1970s Warhol was essentially a society artist, attracting patronage from a diverse clientele that included sports stars, scions and socialites. As Isabelle Graw notes in her book High Price, “the fame in Warhol’s portraits work is something money can buy. Every industrialist’s wife who commissioned a portrait from him in the 1970s found herself transformed into a star.”[6]

The signature style Bernstein employed in the creation of his Interview covers is comparable to – but distinct from – Warhol’s portraits. In Warhol’s method, a polaroid of the sitter forms the basis of the final screenprint. The elimination of detail and tonality creates a high contrast bleached-out image in which only contours of the sitter’s face remain. If colour is present at all it is added to accentuate lips and eyes or else in non-naturalistic flourishes or collaged blocks. In contrast, Bernstein enhances the visage of his subject by adding airbrush, pastel and pencil to the original photo. While some faces radiate the sheen of eternal youth others glow like those of supernatural, otherworldly creatures. The latter is exemplified in the December 1985 issue featuring a wildly stylised depiction of Madonna in psychedelic hues on the cover.

My current eBay dérive highlights how multifarious those featured on the cover of Interview were in this time period. Is there any other magazine to have featured both Divine and Nancy Reagan on the cover? Amongst the hundreds of issues on eBay at this moment are two dating from 1982 that stick out; the February issue featuring Farrah Fawcett and the October issue Michael Jackson. Fawcett and Jackson died within hours of each other, on the same day in 2009, 27 years after their deific faces appeared on these covers. I happened to be in New York on that day – the 25th of June – and was visiting the studio of artist Peter Halley when the death of Jackson was publicly announced. The result of this confluence of circumstances is that I have come to associate the deaths of both celebrities with Halley’s Day-Glo prisons and circuit boards.

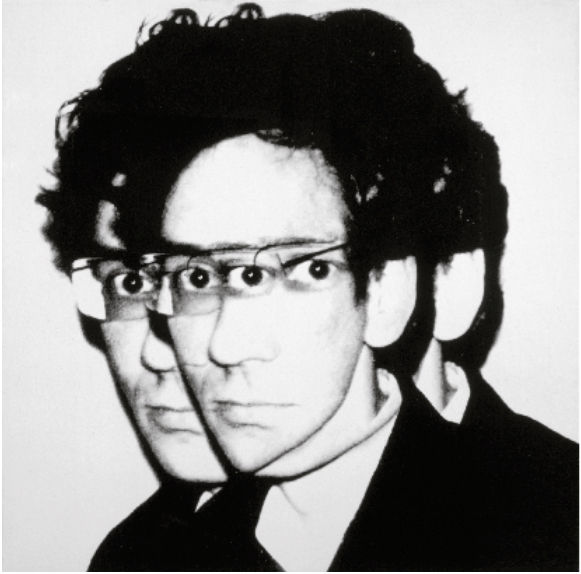

Halley was one of several artists I travelled to New York to meet that summer. I interviewed him via telephone the previous year for an essay I was writing and our conversation had deepened my interest in his work. I wanted to visit his studio, learn more about his paintings and his essays on the “geometricisation of modern life.”[7] I was eager to learn more about Index, the magazine he founded in 1994 as an emulation of Interview. Halley is the only person I’ve ever met who Warhol made a portrait of. The black and white silkscreen hangs in the studio and is unlike any the other Warhol portraits that I’ve seen; his face is duplicated twice with an overlap in the middle, giving him a spectral appearance and the uncanny impression that he has two sets of eyes.

Fawcett’s death was announced the morning of the day I visited Halley. Every newsstand I passed on my way to Chelsea was covered in papers with that epochal red bathing suit photo on the cover. When I arrived at the cavernous studio, we sat at a table from where I could see – far off on the other side – two assistants. One arranged tubs of fluorescent paint while the other used a roller to apply hot pink acrylic to a canvas. Towards the end of our meeting, as the conversation drew to a close, I mentioned Fawcett’s death, to which Halley responded that Jackson’s death had been announced shortly before my arrival. Despite being waves of noise and heat poured through the open windows. Barely perceptible beneath the din was the bassline from Billie Jean, playing on a car stereo somewhere far below.

- The Polaroid taken by Warhol that was used as the basis for this screenprint was taken in 1981 at the time Ross was on the cover of Interview magazine. The Polaroid sold at a Phillips Art Auction in 2013 for $10,625.

- The main difference being the different serial numbers and the fact that my copy was printed in Holland while the MoMA copy was printed in the US.

- Other notable examples of this genre include Need-A-Man Blues by Donna Summer, I Need a Man by Grace Jones, and Searchin’ (I Gotta find a Man) by Hazel Dean.

- Susan Sontag, Notes on Camp in Against Interpretation and Other Essays (New York: Anchor Books, 1990 [1966]), pp. 275–292.

- Ibid

- Isabelle Graw, High Price: Art Between the Marke and Celebrity Culture, trans. Nicholas Grindell (Berlin and New York; Sternberg Press, 2009), p. 170.

- Peter Halley, “Crisis in Geometry”, Arts Magazine, New York, vol. 58, no. 10 (June 1984).