Northland

‘We felt meditative, and fit for nothing but placid staring. The day was ending in a serenity of still and exquisite brilliance. The water shone pacifically; the sky, without a speck, was a benign immensity of unstained light… And at last, in its curved and imperceptible fall, the sun sank low and from glowing white changed to a dull red without rays and without heat, as if about to go out suddenly, stricken to death by that very gloom.’

-Heart of Darkness, Joseph Conrad

In a description of Northland, Noel McKenna notes how at ease and ‘at home’ he felt in that region at the top of the North Island of New Zealand, where ‘differences between the past and the present are difficult to distinguish’.(1) That the artist is enamoured by the region constituting the subject of these paintings is clearly manifest in several of the works in this exhibition. Ostensibly, the vignettes appear to be a travelogue detailing discoveries made on the journey through Northland. Yet a tension present in a number of these works underscores that these paintings are more than the upshot of the artist’s affection for a rural region that ‘looks as though little has altered in decades’.2 McKenna’s investigations convey the specifics and local details of Northland, yet the paintings also function autonomously, detached from the subject matter which unifies them as a body of works, and equally from representation itself.

‘Northland is not inaccessible, but not easy to get to and the roads are not autobahns and some areas are reached by vehicular ferries which go once an hour in peak hour and only carry about 6 cars.’(2) The paintings, whose deceptively naïve rendering initially masks their socio-anthropological qualities, describe a sparsely populated hinterland and reiterate how physical distance and isolation delay the pace of progress, so that that which has become outmoded and relegated to the realms of memory in towns and cities is here preserved from obsolescence a little longer. No references are made by McKenna to the influx of European settlers that began in the eighteenth century or to the subsequent disputes and land wars which followed, yet the quotidian details of these paintings inevitably urges one towards this unfinished history. Of twenty paintings, almost half depict or include places of sectarian worship (Catholic Church Northland; Anglican Church, Northland; Catholic Church, Rawene; etc.), the legacy of those ardent missionaries whose role was central to the early colonisation and regulation of New Zealand, and suggestive of the importance religion once had – and continues to have – in sustaining kinship and constructing a sense of identity amongst a laity.

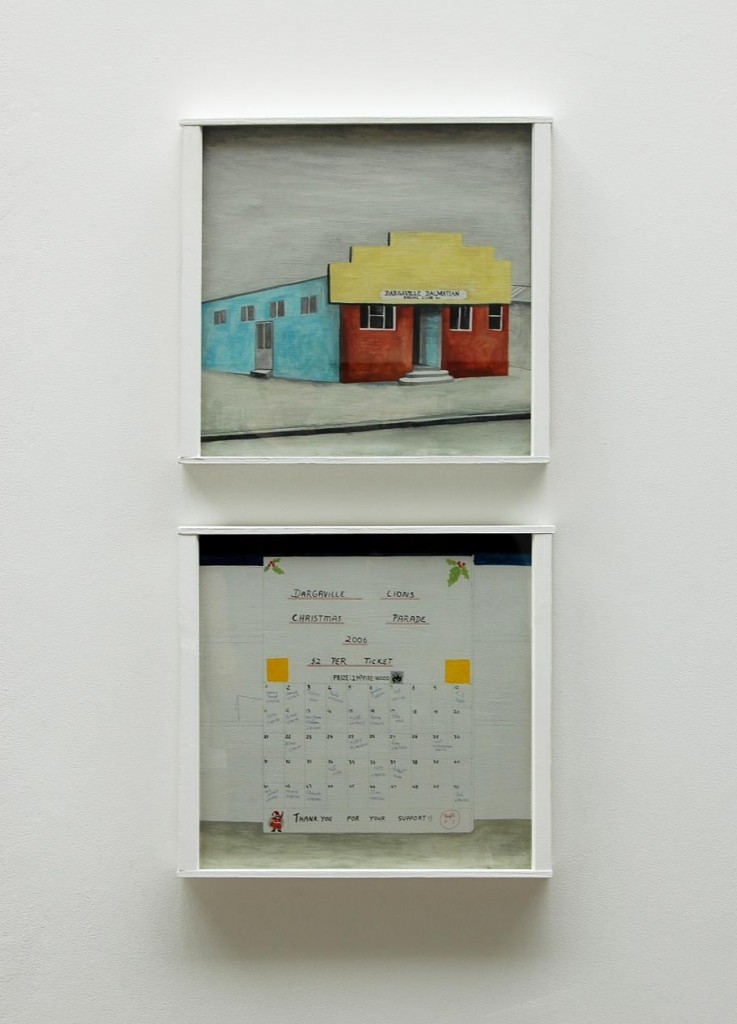

The subtle concealment of historic information within seemingly unexceptional detail is discernible in works such as Dargaville Dalmatian Social Club Inc., an austere painting, which, in addition to drawing attention to the aforementioned complicated and universal necessity for a community to identify and affiliate with their ancestors, alludes to New Zealand’s less well-known settlers – in this case from Dalmatia (a coastal region on Europe’s Adriatic Sea, now part of modern-day Croatia), who, in the final decades of the nineteenth century, contributed to the hybridisation of these relatively diminutive islands in the wilderness of the ocean, settling alongside predominantly Irish, Scottish, Welsh and English populations and erecting wooden churches in vernacular styles as bastions of faith and dignity. Similarly, references to the contentious history of Northland and indeed New Zealand as a whole may be seen in the ‘grammatical’ landscapes distinguishing these paintings, which are never wild or unkempt but are instead defined by an ordered, tamed and almost formal aesthetic. This might be viewed as a reference to the control and restriction invariably imposed upon an indigenous and potentially viable landscape and people in order to confirm ownership and exploit whatever resource might be available to its full advantage.Though few figures are to be seen in this body of work (I have counted only three in total), evidence of the human hunger for control and proclivities toward the dividing, partitioning and apportioning of land via boundaries and incursions are emphasised in these paintings (Sorry Garden Growing; Buildings, Horeke) in which fences, roads, and territorial divisions are ubiquitous.

Though an almost realist character distinguishes these paintings, the assumption that the artist’s intention was to produce mimetic impressions is disrupted by the self-reflexive strategies that McKenna implements. These obstruct straightforward viewings of the work, making ambiguous the degree to which the artist has remained true to seemingly concrete ‘subject matter’. For, though Northland constitutes an anchor point of departure, the works themselves possess a stark, airless and static quality, painted almost awkwardly so as to negate the assumption that reproduction is the intention, and bringing to the fore the idea that these images may be viewed without reference to the duty of representation. Something is askew. While rooted in the specifics of their locality these faded – as though sun-bleached – sylvan scenes could be almost anywhere and function successfully without being bound to the history or landscape. When viewing them, one cannot avoid the suspicion that the scenery has been modified and manipulated to suit the artist’s requirements. It flickers between the mimetic and the symbolic, while also alluding to local specifics. And yet there emerges too the possibility that these landcapes are vehicles for

This ambiguity – something McKenna seems to be fascinated with (3) – is undoubtedly one of the most interesting aspects of these paintings. The manner in which McKenna conflates components that possess poetic and symbolic properties is apparent in the typically melancholy Child’s Grave, Dargaville. The scene – anchored in experience, perhaps – is (not unusually) devoid of characters, creating a tone of desolation while beckoning the viewer to intrude. The juxtaposition of the rocking chair atop the gravestone with the tree stump, the crossroads in the pathway and the four fragile-looking trees silhouetted against the sky (echoing the four gravestones in the image), interrupts any assumption that this image is documentational. It appears precise but also contrived – as things do in one’s dreams or memories – where the visual memory becomes infiltrated and altered by emotion and imagination.

As previously noted, there is in these works a tension between the tendency toward reportage, motivated by a desire to relay that which is observed and experienced, and a metaphysical and stylised approach that seeks to create psychologically suggestive landscapes. Beyond this is the idea that the artist is, in fact, also interrogating, in a knowing and extremely expert way, the medium in which he is working – and, indeed, the nature of representation itself.These fluid and unsteady images hover on the edge of abstraction, and what seems solid and definite becomes less so when subjected to prolonged analysis. Painted on uniformly sized canvases, McKenna’s paintings evoke those of Fairfield Porter (1907–1975), who remained loyal to figurative painting throughout his career by devising a unique idiom in which the mimetic was constantly disrupted by formal and stylistic gestures that highlighted the flatness of the image and ultimately the artifice of painting.The paintings that constitute this show are also distinguished by this schizoid hybridity, in that they oscillate in and out of being representational.A further complexity arises when one realises the extent of the repetitious process, suggesting a conceptual ambition. Certain atmospheres and tones recur throughout the twenty paintings as frequently as distinctive motifs and compositions – planes of flat colour often divided by the presence of a horizon line. McKenna seems determined to draw the attention of the viewer to the manner in which each image has been created and constructed from nothing to something. This exposure of the structure of the image is most evident in those paintings where McKenna’s pencil lines are highly visible upon the gesso.

This psychological recoding of the real is at once a transformation and an abstraction, and it would seem that, ultimately, the longer one views these works, the more the images dissolve into an assemblage of interconnecting planes, so that the character of this body of works relates less to its recognisability or specificity than to the qualities inherent in its form. Indeed, there is often a sense in these paintings that the true priority of the artist is to investigate the qualities inherent in the purely formal world, in which everything may be reduced to shapes, textured surfaces and light fractured into forms, locked within McKenna’s distinctive frames.

Something about McKenna’s journey to Northland evokes those made by the cultivated avant-gardists who, in the last years of the nineteenth century, ventured out from the sophisticated urban milieux they inhabited into rural environments and settlements that had not fully escaped the onslaught of technological progress or an emerging tourist industry, but had yet remained somewhat immune to an increasingly chaotic pace, owing to their geographical isolation. While most of the artists went in search of ‘backward’ provincial communities, the artworks emerging from such sojourns were rarely precise depictions of the people and the landscapes, but often technically sophisticated images conceived with a certain nostalgia for a bucolic, idyllic life.The result of this was often a fascinating construct that combined the artist’s own unique sensibility with adapted images of actual locations. Similarly, it would seem that in some ways the rural region to which McKenna journeyed served only as a means to an end for the artist, resulting in work that is, ultimately, a profound and problematic conflation: paintings that resist neat categorisation and sit stubbornly on the fence, conflating memories and images of the real world with those of an interior landscape and interrogating the meaning and the visual fabric of both.

(1) Extracted from a short essay on Northland by the artist.

(2) Ibid.

(3) Ibid.