Notes on Psi

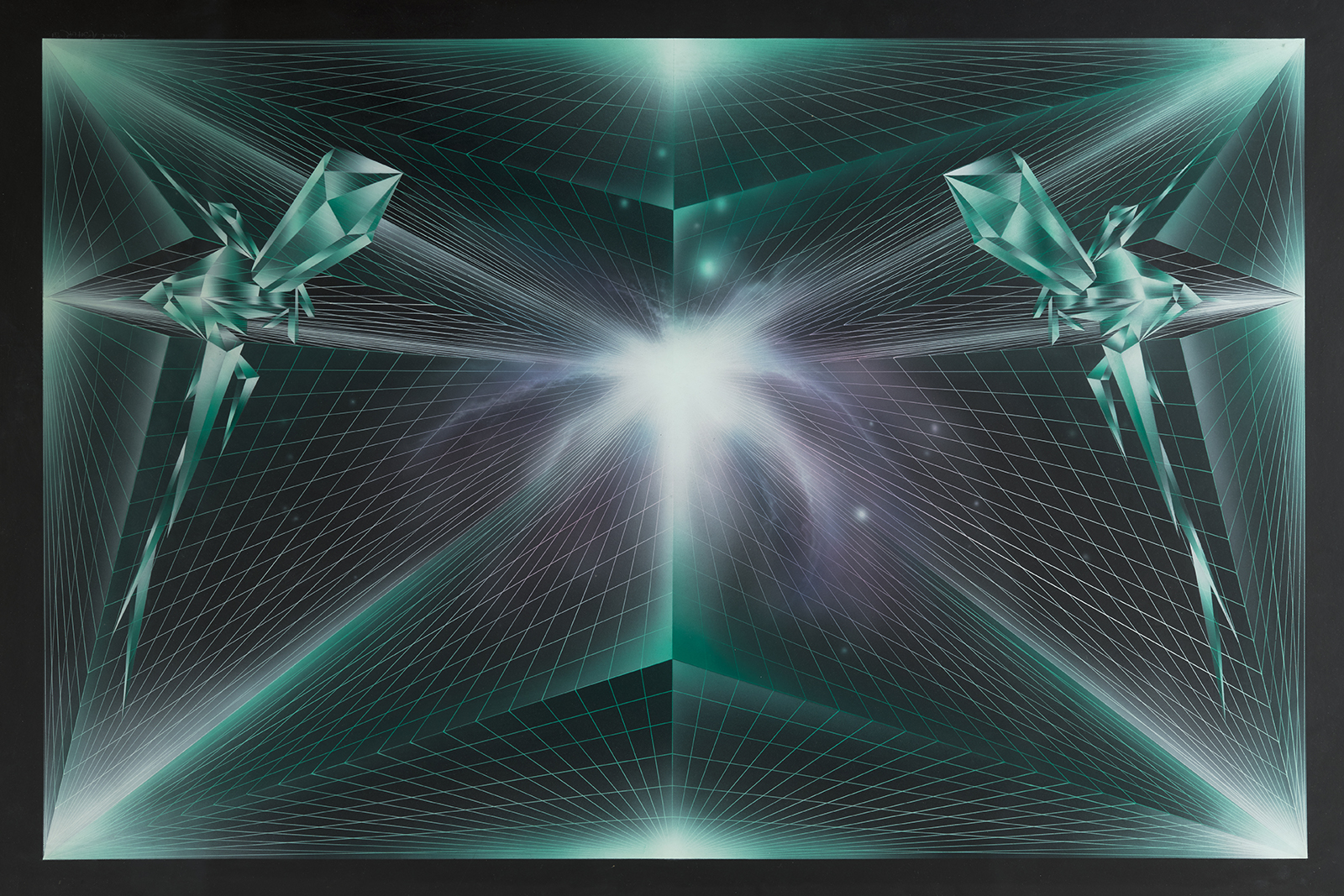

This project originated from a conversation between Navine G. Khan-Dossos, Sofia Stevi and myself in Maastricht, in December 2014. Our shared interests in Psi phenomenon and parapsychology led us to develop a group exhibition primarily concerned with the transfer of thoughts from one person’s mind to another. The seven invited collaborators – Brian Dillon, Gary Lachman, Quinn Latimer, Paula Meehan, Sophia Al Maria, Marco Pasi, and Mark Pilkington – were asked to provide in writing an idea or image that possessed some personal significance. These texts were then interpreted by artist Navine G. Khan-Dossos and translated into gouache paintings upon the gallery walls of Fokidos, Athens. In most cases the contributed writings originate from dreams or liminal states of mind. In other cases the text is more akin to a body of images that preoccupies the contributor; in one instance the image or ‘scene’ is one the contributor was striving to summon in his mind but seemed paradoxically unable to do so. In some, the material is presented in a raw and ambiguous form, or else it is more finished and composed. The act of producing the wall paintings took place after Khan-Dossos had spent several months considering these writings, envisaging them in her mind and imagining if and how they might relate to each other. It is perhaps at this stage in the process that she assumed a role comparable to that of the medium; a conduit through which the thoughts of another – that would usually never be given any physical form – are made visible. Through this ‘channelling’ process some of the sensibilities and stylistic idiosyncrasies of the artist are inevitably imposed upon the artwork, but the resultant painting is ultimately a work authored by several individuals. Artworks that emerge from this process might be seen as a synthesis of two personalities; what might be termed a ‘third mind’(1).

This dynamic between author ship and production is central; the project aims to devise a situation in which subjectivity could be shared and transformed into a transpersonal work of art. In going beyond the individual creator and focusing instead upon the polyphonous potential of the group, this project is an investigation into the collective dimension of consciousness and creativity. What might be termed the ‘creative process’ never occurs in solitude but inherently entails complex communications between artist, artwork and viewer. The title of this project (comprised of this publication and the accompanying series of wall paintings) refers to the term ‘Psi’, coined by the parapsychologist B.P. Wiesner in 1942 to describe the spectrum of phenomenon contested by orthodox science – including clairvoyance, clairaudience, telepathy, precognition and psychokinesis (2) . The source of this term is the 23rd letter of the Greek alphabet and the first letter of the Greek word ψυχή (psyche), which refers to the human mind or spirit, but also to the psychological structure of an individual. The spectrum of Psi phenomenon seems relevant when considering the unique way visual art can communicate and disperse knowledge and ideas via unwritten and unspoken methods. One of the central aims of this collaborative project is to emphasise the idea that subjective intuition activated through engagement with works of art is a vital and valuable part of a person’s consciousness and may ultimately contribute to a situation in which consciousness can be shared between people. The period in the 1940s, when the term Psi emerged, marks the end of an age in which the spectrum of phenomena proposed by parapsychologists in the late 19th and early 20th centuries was still considered worthy of serious consideration (3) . Today, there exists much scepticism towards the possibility that occurrences involving psychic activity even take place. Universities that were once supportive of parapsychological research are now no longer willing to affiliate themselves with such fields of investigation (4) . Conventional science and psychology, refuse to accept that parapsychology is a ‘proper’ science, dismissing the entire field as pseudoscientific (5). One of the reasons parapsychology – and Psi phenomena – is so often dismissed is because modern science, with its physicalistic orientation, is itself at a loss to provide definitive explanations as to how the human brain is capable of giving rise to conscious experience. Regardless of the accuracy of the theories proposed by parapsychologists, they nevertheless offer useful models for thinking more openly around how cognition and perception function.

In his Phantasms of The Living (1886), Frederic W.H. Myers describes a region of the unconscious that he terms the ‘subliminal self’ and proposes the existence of a ‘metetherial’ world. According to Myers (who co-authored the text with Edmund Gurney), this world was comprised of a depository of images formed from electromagnetic ether that could potentially be accessed by attuned individuals. Myers proposed that the human mind could temporarily reach this web of images or projections which would most likely be perceived as a ghostly apparition. Ideas like this were widespread in the late 19th century and were elaborated upon by parapsychologists in the 20th century such as J.B. Rhine. More recently, John Palmer suggested that certain patterns of brain activity can give rise to integrated ‘packets’ of psychic content called ‘Psiads’(6) . Once formed, these Psiads exert psychokinetic effects on the brain before ‘drifting’ free and coalescing with other host brains. Like a virus, these Psiads go on to produce activity or mental content similar to that originally occurring in the ‘mother brain’. What unifies such parapsychological ideas examined above is the notion that the brain and nervous system operate as a filter, selecting and organising content from extensive subliminal domains for inclusion in the limited field of everyday awareness. The suggestion is that if this filtering is disrupted, previously occluded material or ‘content’ can emerge.

In the late 19th and early 20th century individuals affiliated with science and psychology were not the only ones engaging in research into Psi phenomena. Numerous spiritual leaders claimed to receive material from discarnate spirits that became the basis for important teachings, leading to the emergence of several esoteric systems. This is exemplified in the material allegedly communicated to Helena P. Blavatsky via the Mahatmas, or Ascended Masters that eventually formed the basis of The Secret Doctrine (1888), Blavatsky’s masterwork on the origin and evolution of the universe and humanity, and the most important book of the Theosophical movement. Several years later, in 1904, The Book of the Law was ‘received’ by Aleister Crowley, said to have been transmitted via the spirit Aiwass. From this, the esoteric movement known as Thelema developed – just one of many belief systems that emerged throughout the 20th century founded upon supposed communication with spirit entities. In the late 19th and 20th century instances of Psi interaction also led directly to the emergence of significant works of art. Several artists closely affiliated with the emergence of literary modernism were informed by invisible presences. For six years, Irish poet W.B. Yeats was engaged in channelling sessions with his wife Georgie that resulted in substantial quantities of automatic writing. In these sessions Yeats would pose questions to his wife – who was apparently in a trance-like state – which would be answered by several spirit entities. As the body of material increased over the years, Yeats began to see in it the basis of a complex, esoteric philosophical system. Eventually Yeats would formalise this channelled material into his treatise A Vision, first published in 1925. There are also numerous instances in the history of visual art in which communication with spirit entities has influenced the work of artists. One of the most prolific artists to have produced work via the channelling process is Hilma af Klint, who is now recognised as a pioneer of pure abstraction. Allegedly af Klint began regular conversations with the spirit that would become her long term collaborator in the 1890s during participation in spiritualist séances with four female friends. This group referred to themselves as ‘The Five’ and were the recipients of messages from spiritual entities calling themselves Gregor, Clemens and Amaliel. Through Amaliel, af Klint was introduced to a universal language of symbolism that was to form the foundation for her abstract painting. In the beginning, the spirits apparently directed af Klint’s hand in the work. Later in her career, af Klint familiarised herself thoroughly with the work of Blavatsky and claimed that although a spirit guide remained by her side, his instructions were mediated in words and appeared as images to her inner eye that she then interpreted on canvas.

In the interwar period the Surrealists – who were persistent in their efforts to explore the more arcane aspects of human consciousness – attempted new ways to unlock creative potential. One of these was through the dream and the other was the séance. M.E. Warlick has outlined how, from 1922 to 1923, several Surrealists conducted séances not necessarily to commune with spirits but to enable them to access what André Breton defined in his Manifeste du surréalisme (1924) as ‘pure psychic automatism’. In the initial phases of the Surrealist movement, ‘pure psychic automatism’ was essential in allowing its members to access what they termed the ‘true functioning of thought’ (7) . To begin with, ‘pure psychic automatism’ was applied as a written technique but it soon extended to the production of graphic or pictorial automatism, a gestural equivalent followed later by techniques based on frottage, and decalcomania. This evolution into predominantly visual techniques gave way to practices that were more concerned with the surrender of control via methods of chance that connected to physical process (8) . Although initially fruitful these experiments did not completely liberate the Surrealists from the aesthetic rules that they sought to escape from, instead developing into a formal methodology more concerned with stylistic effect. In their early years the work of the Surrealists was characterised by a desire to give the dream or liminal state of mind priority, in the hope that the resultant material might be somehow informative or capable of exposing that which would otherwise remain concealed. A similar motive lies at the centre of this project, as does a desire to examine the thresholds of transfer between one mind and another.

The work of artist Susan Hiller has informed much thinking around this project and many of her own experiments act as precedents. Hiller’s Draw Together (1972) was conceived specifically as a kind of ESP experiment following her reading of Upton Sinclair’s book Mental Radio (1930), emerging as an experiment into the possibilities of thought transfer. Hiller invited 100 artists from around the world to take part in this project. It featured Hiller gazing at images cut from magazines for extended periods of time; she then attempted to send out these images to individuals in different parts of the world at different times. These individuals would then execute drawings that, in some cases, were said to bear some connection to the ‘original’ image. This project is thought to have led to the work Sisters of Menon (1972–79), which was created entirely through automatic writing. Hiller, however, was not alone in working with such methods. In the early 1970s a number of artists, particularly those working in the realms of performance or Fluxus events, including Marina Abramović, Joseph Beuys and Carolee Schneemann, produced works in which some form of Psi activity was key to their meaning.

While the methods of the séance are to some extent referenced in this project, the main intention is not so much to channel spirit entities but to create a scenario in which traditional modes of authorship are altered and explicitly expanded – where a group mind becomes possible. The notable difference between this project and others outlined above is that, while the basis of the exhibition centres around a process of channelling, the mediator – Khan-Dossos– is very much part of this human world, and the messages she is translating themselves come from living beings.

In addition to the transpersonal nature of the project, the process of giving form to what might otherwise be dismissed from more rational modes of thought is crucial. The manner in which the material – originating in the minds of the contributors – is treated and ‘processed’ gives substance to evanescent information. The act of writing this material down was an important stage, but the translation process carried out by Khan-Dossos gives the material a new symbolic potency. The material leaves the realm of language – a medium which is limited in its capacity to communicate – and becomes an image. The verbal made visual. This process could be seen as an iteration of the possibility that ‘thoughts are things’ comparable with physical actions and commensurable therefore with physiological law. In concentrating upon liminal states of mind and the way in which invisible exchanges occur between individuals, this project undermines the idea that the physical world is all that exists and that ‘oneself is nothing more than one’s physical body’ (9) . It could be argued that the reason the existence of Psi, and other forms of anomalous phenomenon become more contentious as time progresses is symptomatic of a tendency toward techno-rationalisation, which has intensified over the course of the past century. The increasing incredulity towards phenomenon that seemed entirely plausible a century ago can be viewed as evidence that we are being coerced ever further into self-restriction, into narrower perceptions of ourselves and our potential. However, visual art offers a space of experiment, where phenomenon that is to some extent inexplicable – in that it cannot be explained according to the codes of rationality – can be examined and rethought. Traditionally, human ‘progress’ has to date denied what might be termed instinctive or imaginative perception, so that intellectual perception is permitted to dominate. And yet the most profound and important things can be felt and experienced, even whilst they shirk from comprehensive human expression. Visual art’s vitality rests in its capacity to create and communicate knowledge and ideas via methods which are often unwritten and unspoken. It speaks to a sphere of the psyche that unconsciously exerts an enormous influence upon our lives. Visual art thus stakes the claim to a site of pure mind/matter interaction.

(1) The Third Mind is the title of a book by William S. Burroughs and Brion Gysin published in 1977 (The book was first published in French. The English edition the following year). In it they considered how the collaborative process can result in the emergence of a new author: ‘It is not the history of a literary collaboration but rather the complete fusion in a praxis of two subjectivities, two subjectivities that metamorphose into a third; it is from this collusion that a new author emerges, an absent third person, invisible and beyond grasp, decoding the silence. The book is therefore the negation of the omnipresent and all- powerful author – the geometrist who clings to his inspiration as coming from divine inspiration, a mission, or the dictates of language.’ (New York, 1978. p.12 )

(2) J.B. Rhine, ‘The Present Position of Experimental Research into Telepathy and Related Phenomena’, Proceedings of the Society for Psychical Research, 47, part 166, 1948, pp. 1–19.

(3) In 1957 the Parapsychological Association was formed and became affiliated with the American Association for the Advancement of Science in 1969.

(4) Although there are some exceptions (such as Edinburgh University) many of the laboraties established for the investigation of parapsychology in the past such as those at Duke and Stanford University have disbanded.

(5) This is epitomised in the work of individuals such as Ray Hyman who has been referred to as the leading critic of academic parapsychology.

(6) Douglas M. Stokes, The Conscious Mind and the Material World: On Psi, the Soul and the Self, Jefferson, North Carolina, 2007, p. 103.

(7) The first Surrealist manifesto, written by Breton in 1924, states: SURREALISM, noun, masc., Pure psychic automatism by which it is intended to express, either verbally or in writing, the true function of thought. Thought dictated in the absence of all control exerted by reason, and outside all aesthetic or moral preoccupations. Manifestoes of Surrealism, Michigan, 1969.

(8) This is the bridge that connects Surrealism to painters working in the US in the post-war period (known as the Abstract Expressionists), such as Jackson Pollock.

(9) Stokes, p. 3.