Poems I Will Never Release

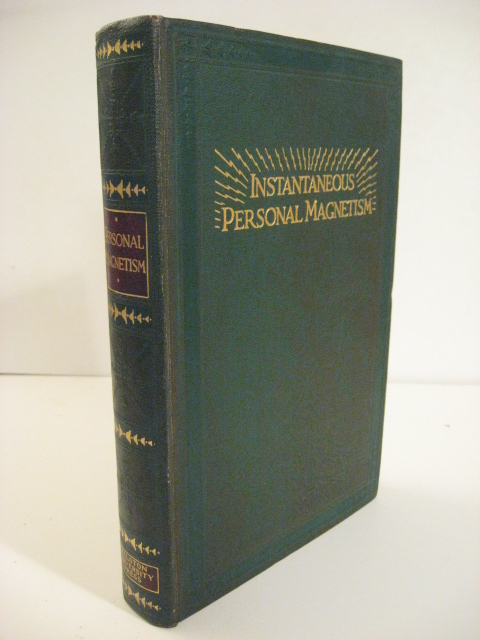

In 2016, at an edition of Riga’s Survival Kit arts festival whose theme was the ongoing ‘esoteric turn’ in contemporary art, I saw Chiara Fumai give a workshop on making magic sigils. She demonstrated to a rapt audience how they could write down their desires and then remove several letters to create a talismanic symbol. A charismatic performer, the Italian artist captivated the audience with her conviction that one could effect change in one’s life by generating these pictograms. The event was enlivened by Fumai’s irreverent humour and tendency towards satire. These are aspects of this artist, and her practice, that are now overlooked and have been eclipsed to some extent by her untimely death, in her late thirties, in 2017.

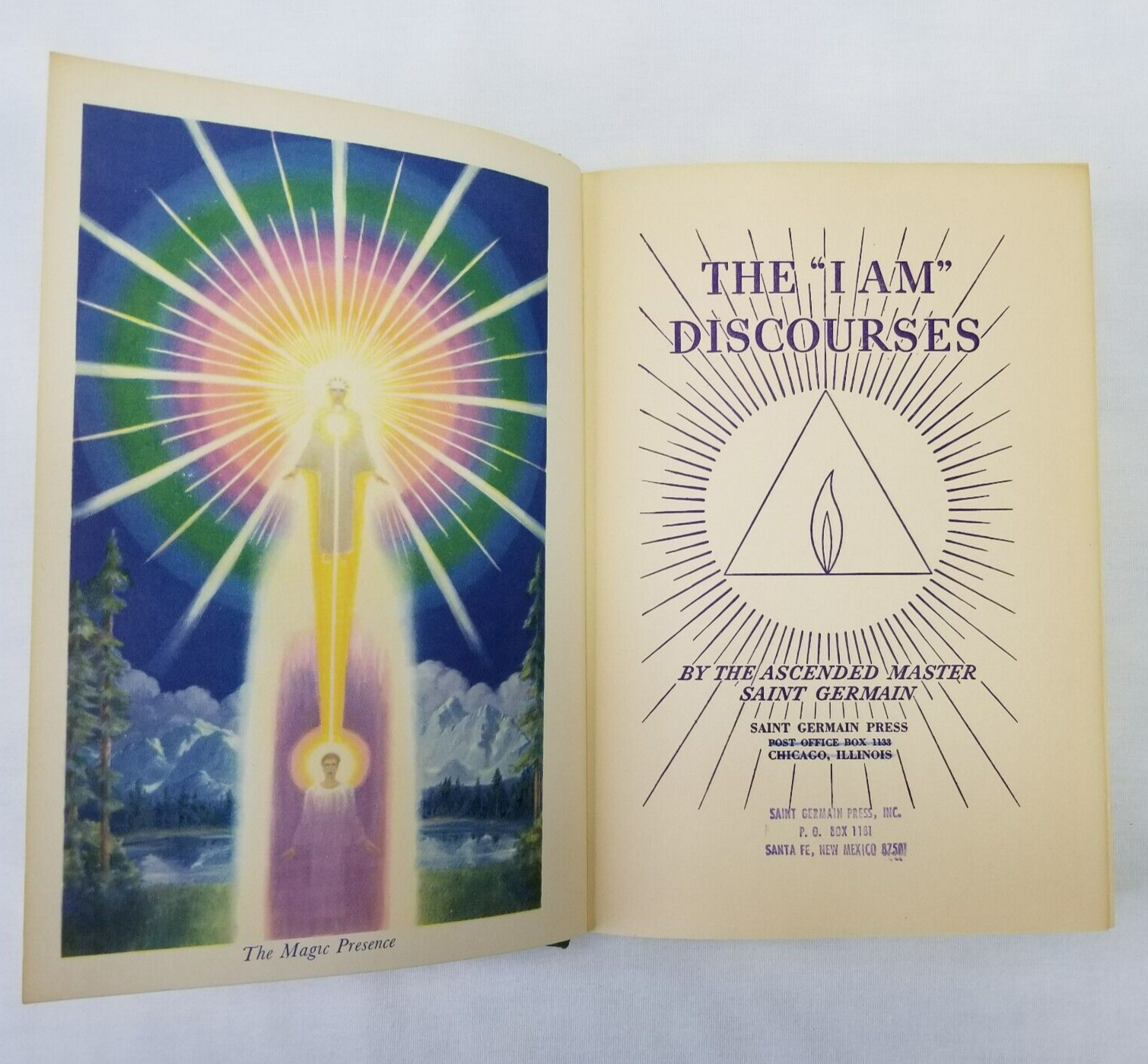

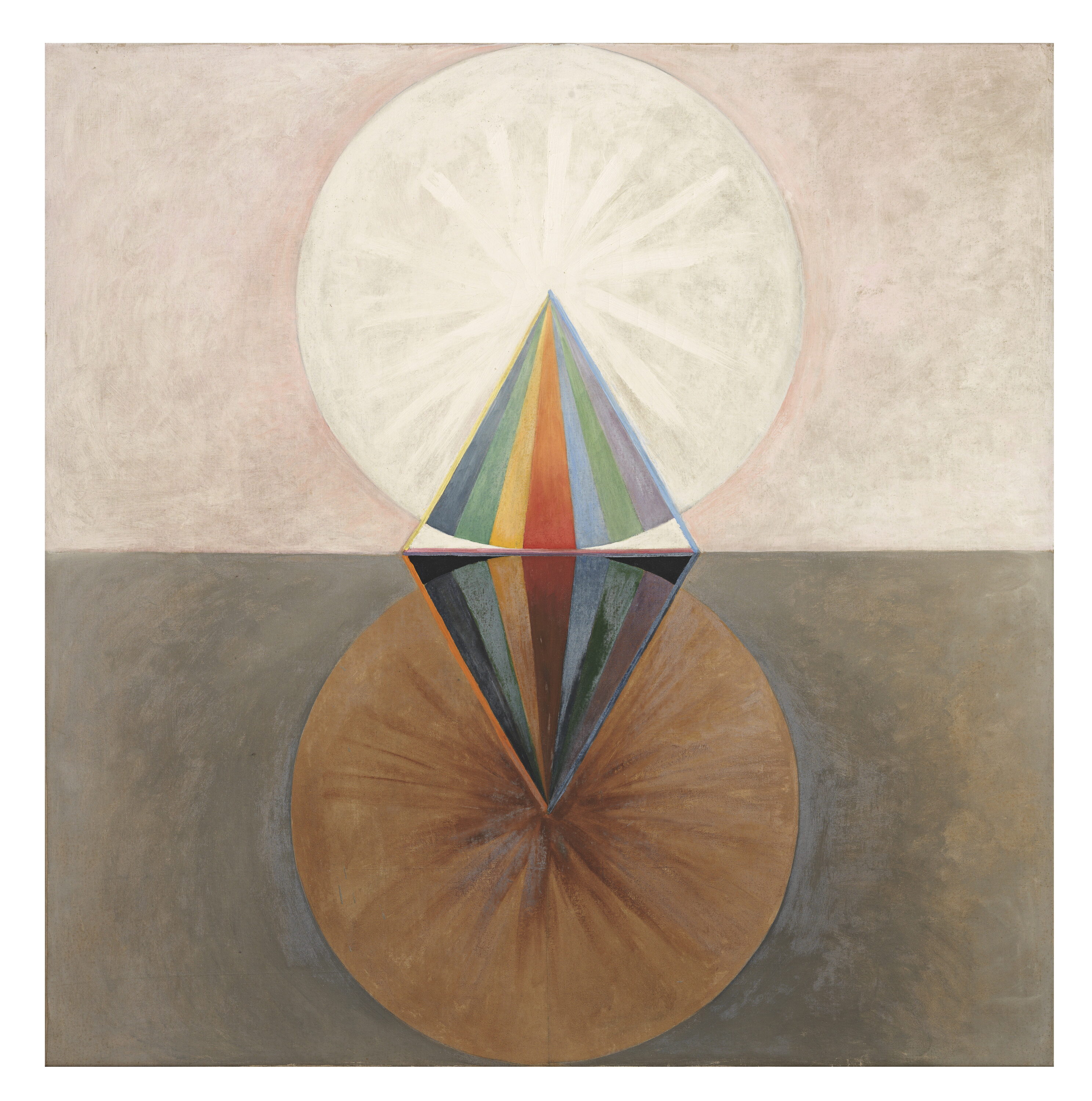

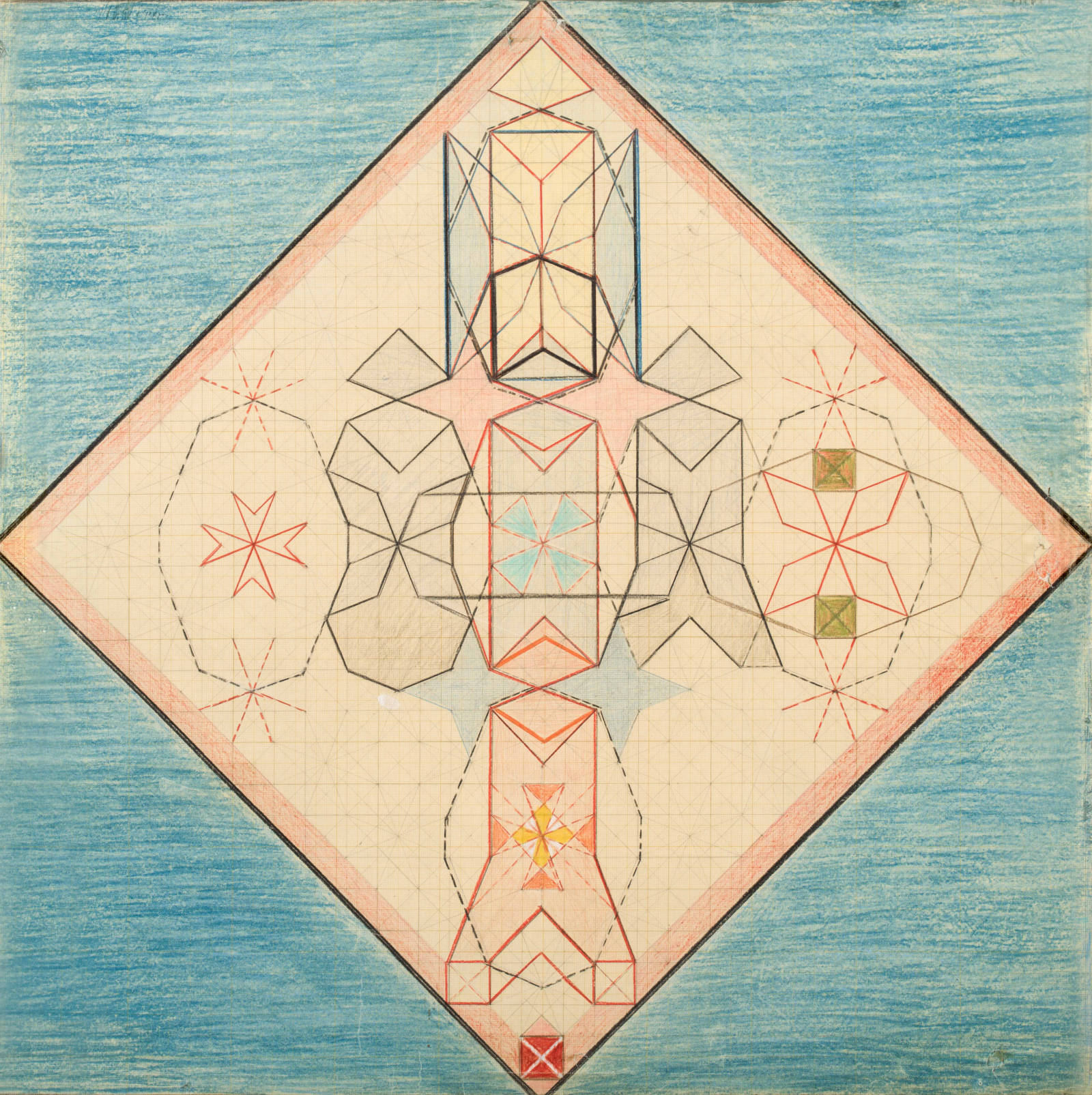

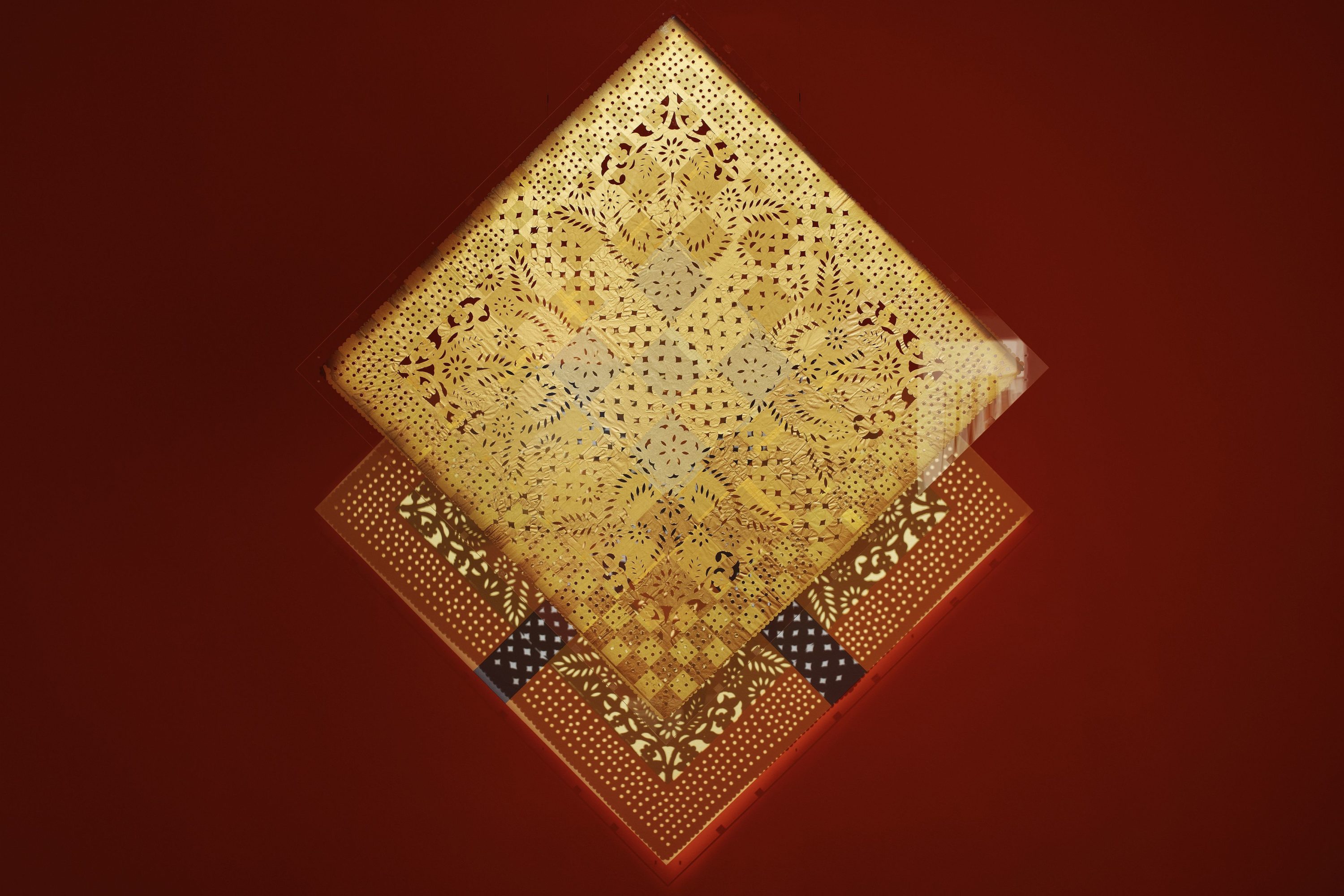

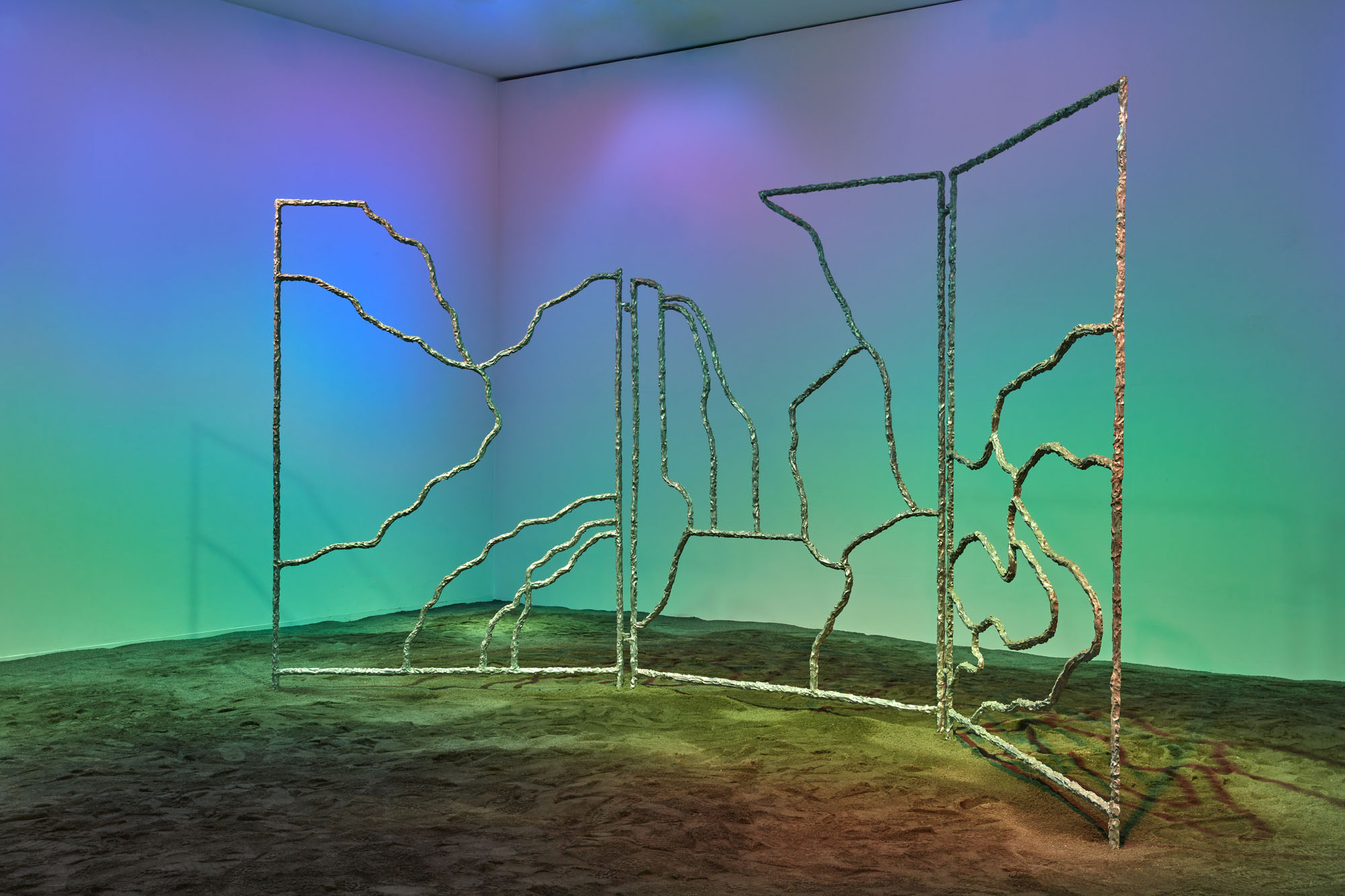

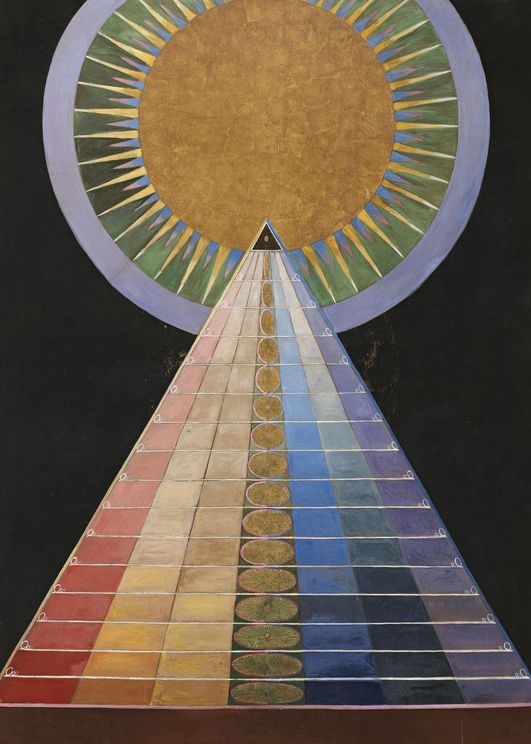

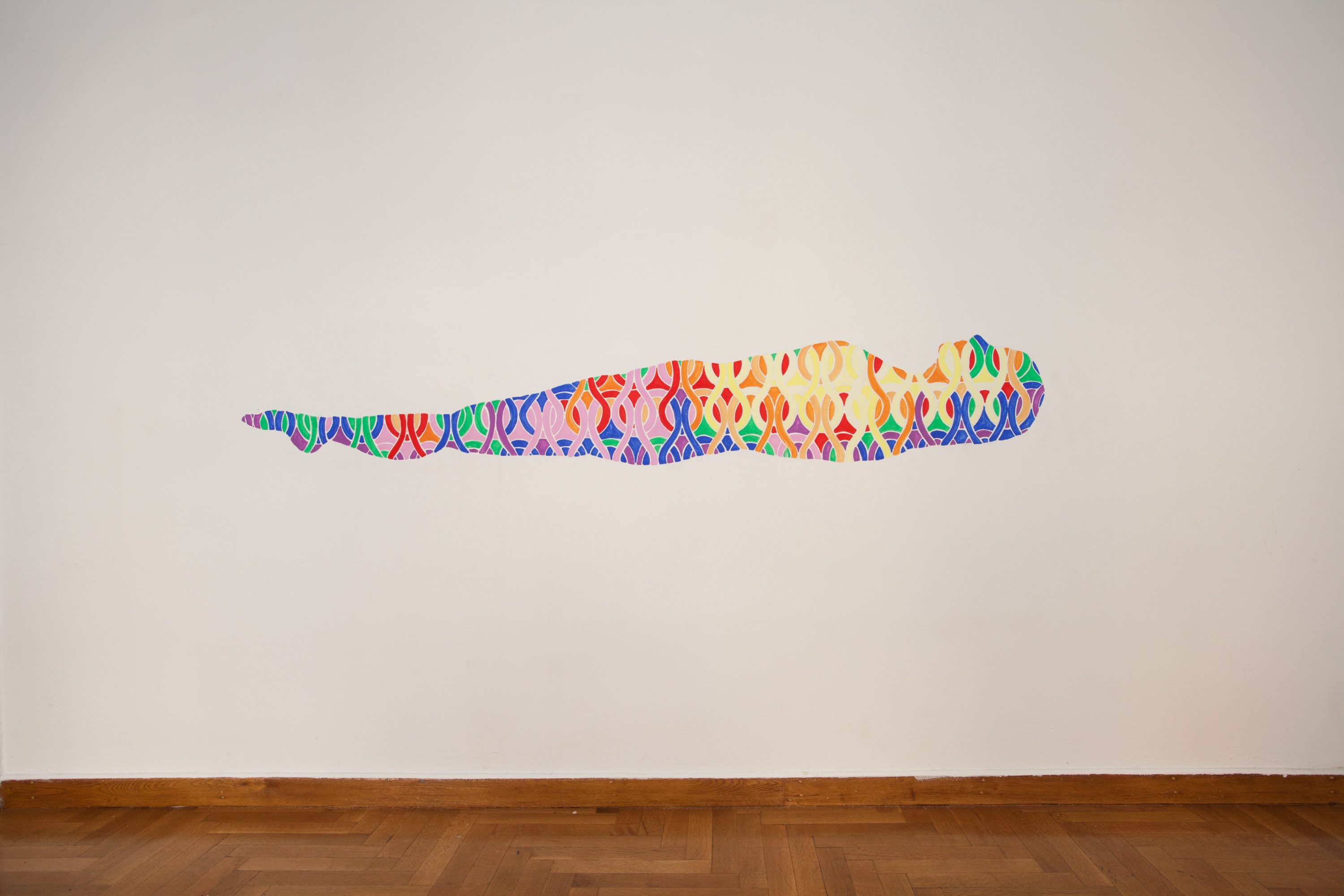

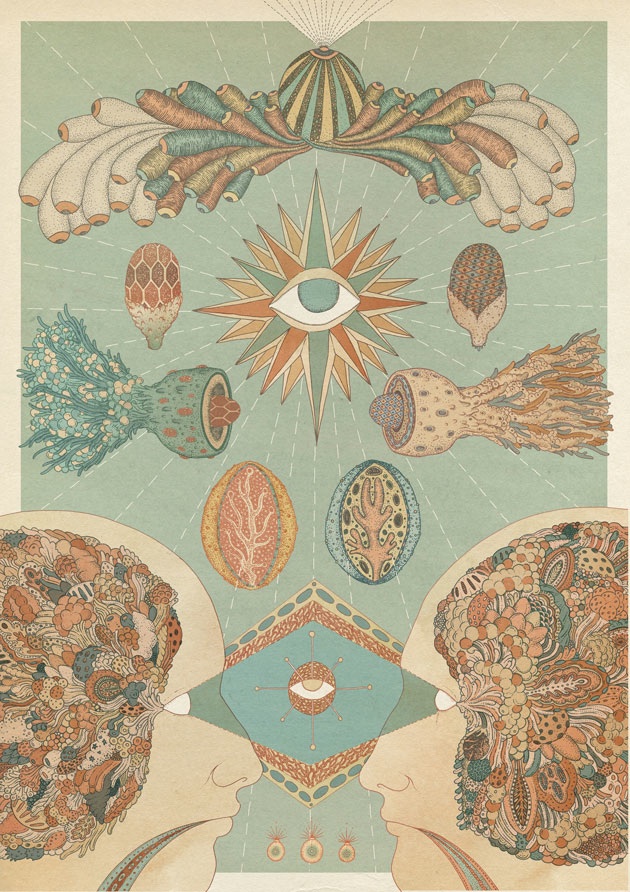

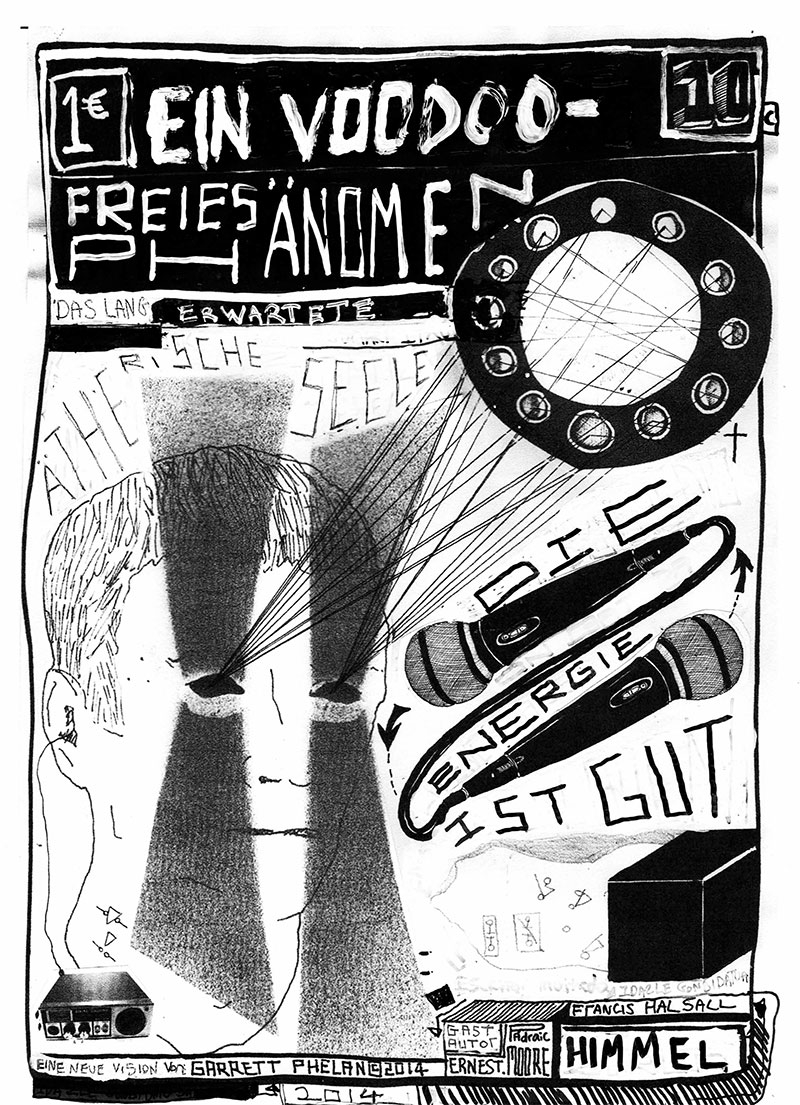

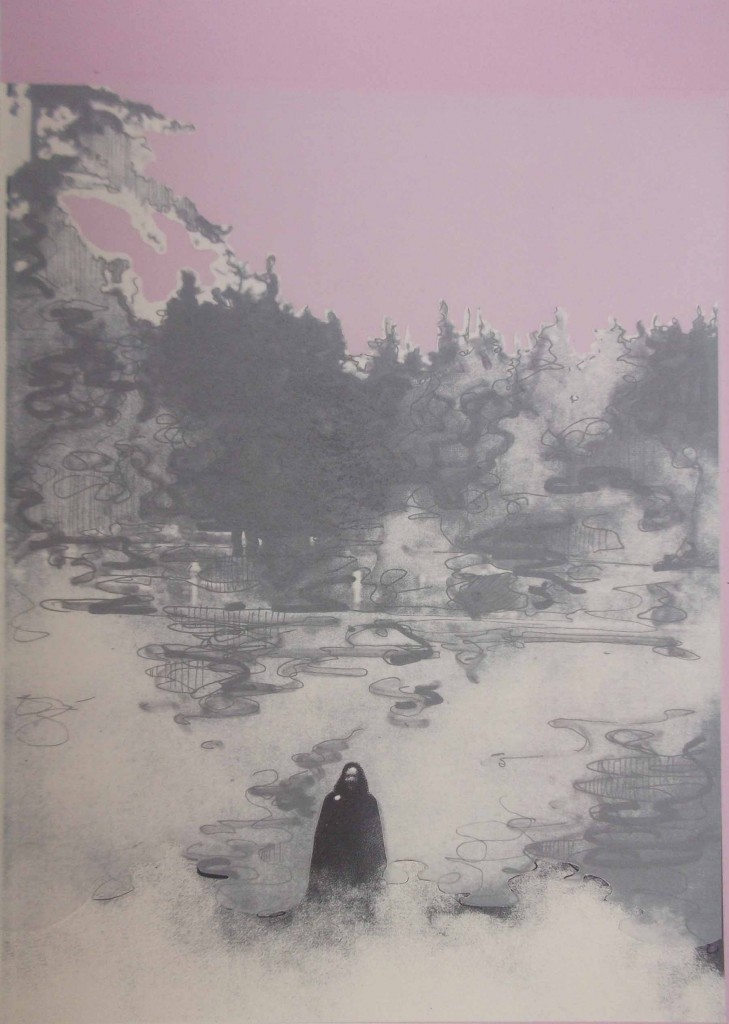

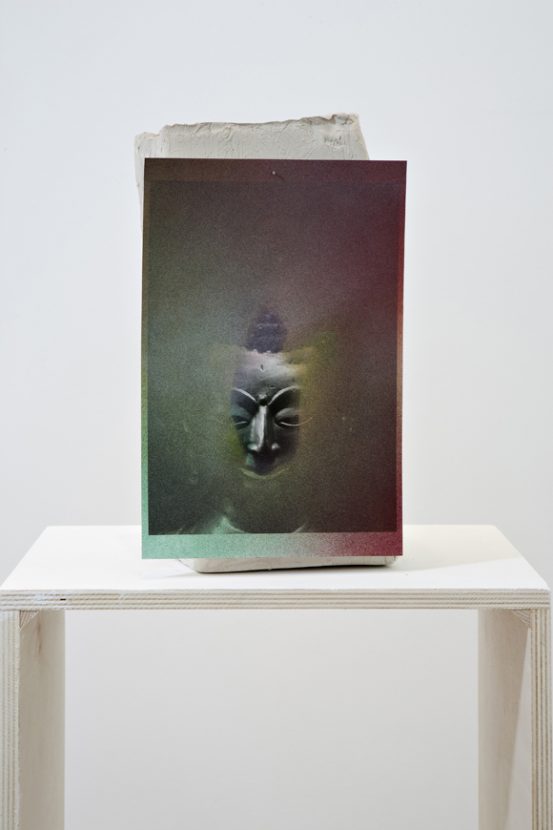

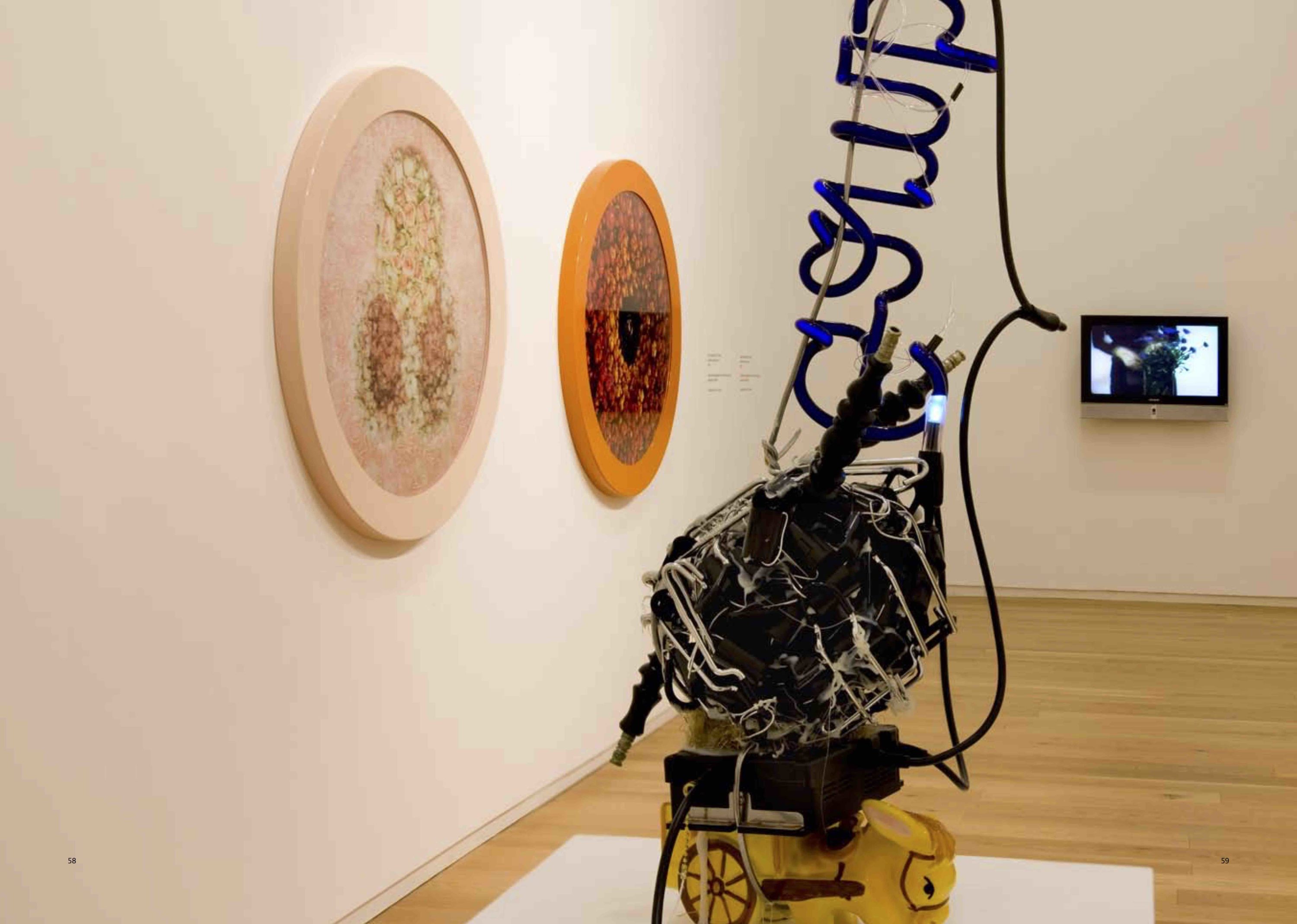

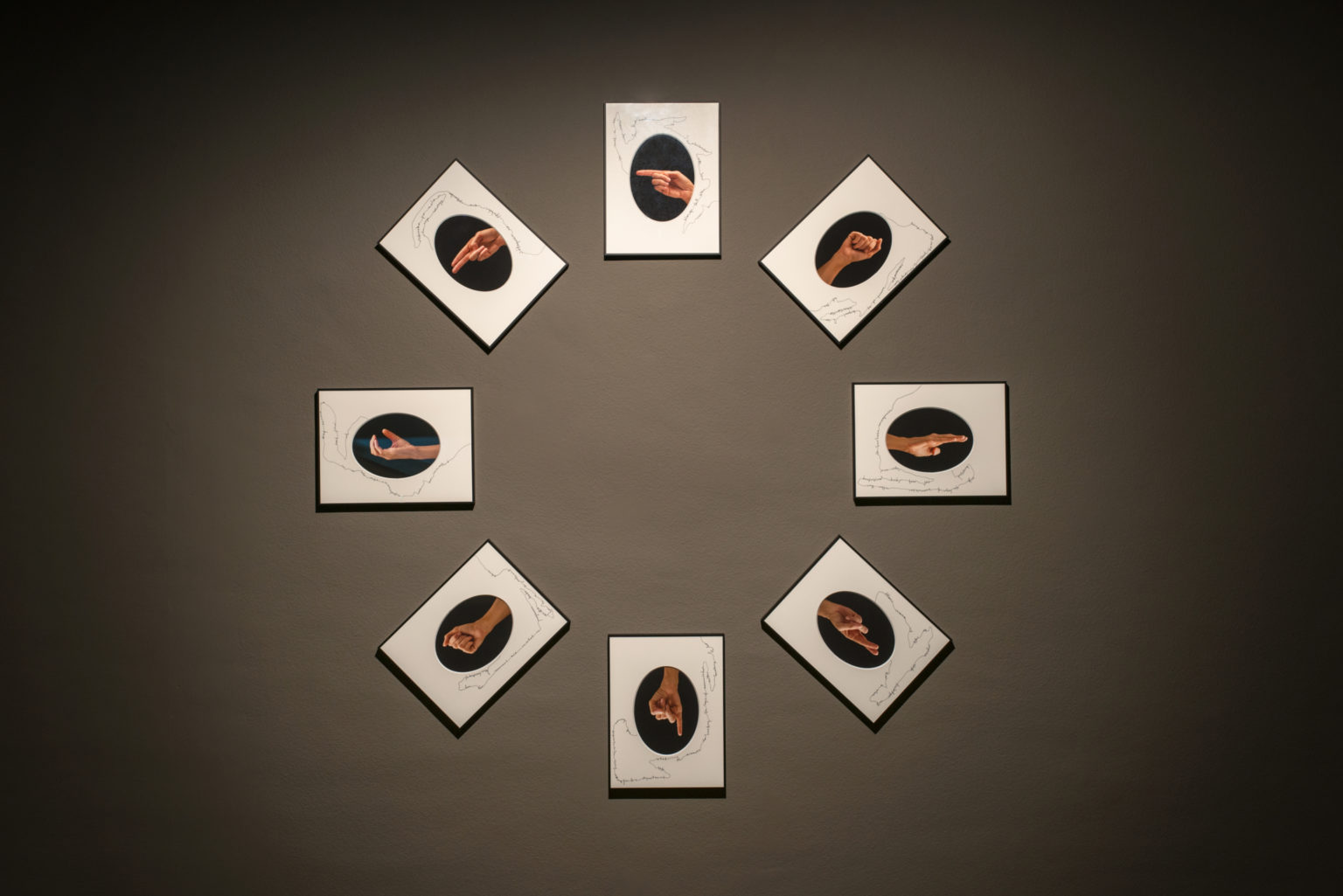

Fumai was essentially a bricoleur, one who sampled elements from a multitude of disparate doctrines. Her magpie methodology is particularly conspicuous in this Brussels chapter of her travelling retrospective, which features works dating from 2007 to 2017. Take, for example, the sprawling mural This Last Line Cannot Be Translated (2017), which adorns the walls of the largest of La Loge’s gallery spaces and could be described as syncretic. Fusing fragments of gnostic and kabbalistic symbolism with intentionally impenetrable magickal formulae of Fumai’s own making, it epitomises her attitude: referencing strands of occult wisdom to antagonise the intellectual, cultural and religious institutions that govern contemporary society. All these symbols, meanwhile, are surrounded by a jagged line that looks like automatic writing but is interrupted by spray painted symbols. Like several pieces in this exhibition, the mural is a reconstruction that has been authored by The Church of Chiara Fumai, the custodial organisation founded in 2018 to promote and preserve her formidable legacy.

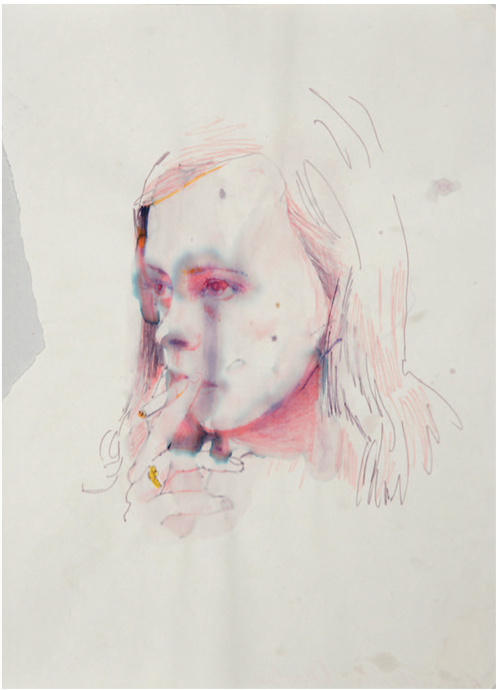

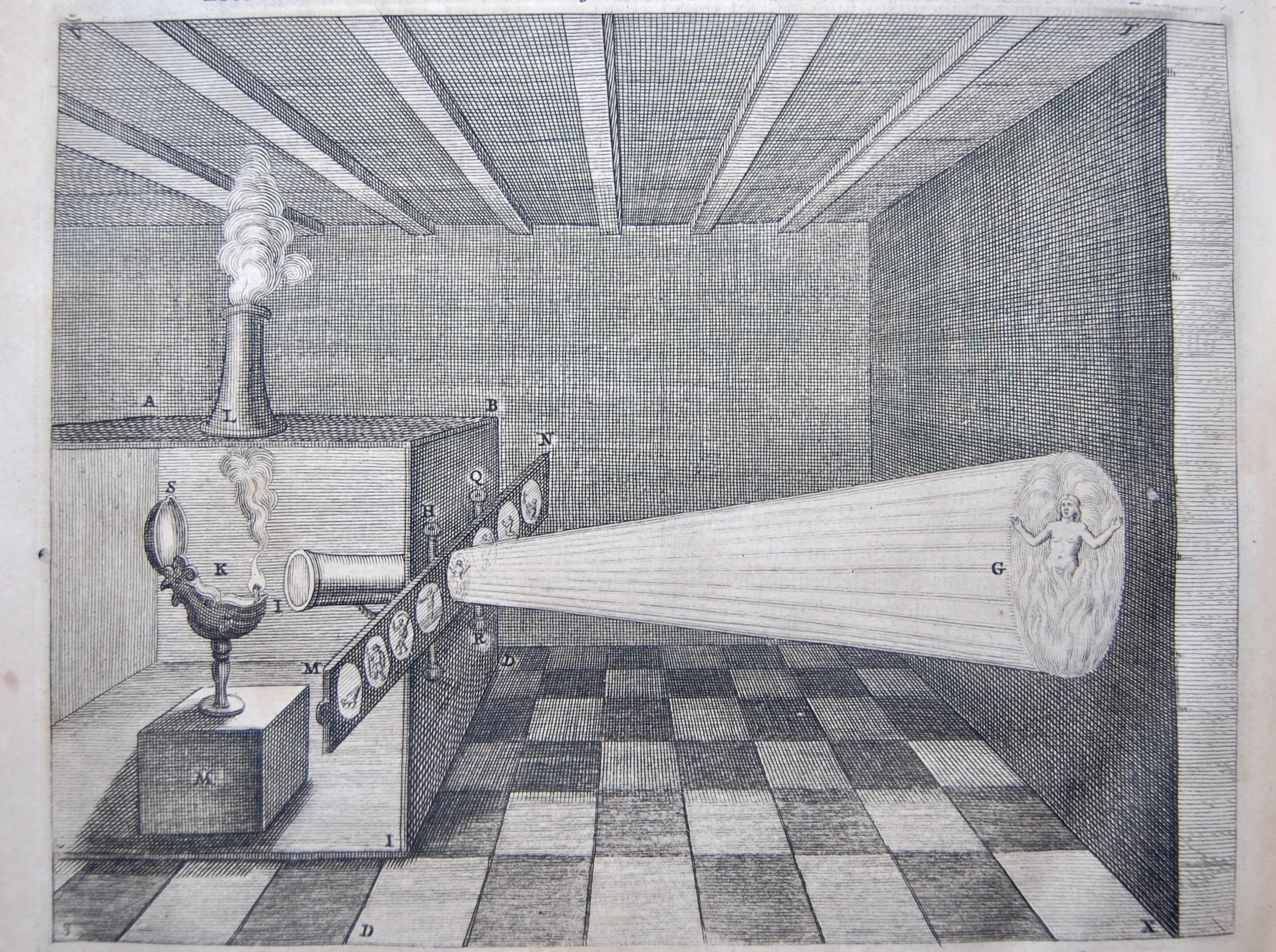

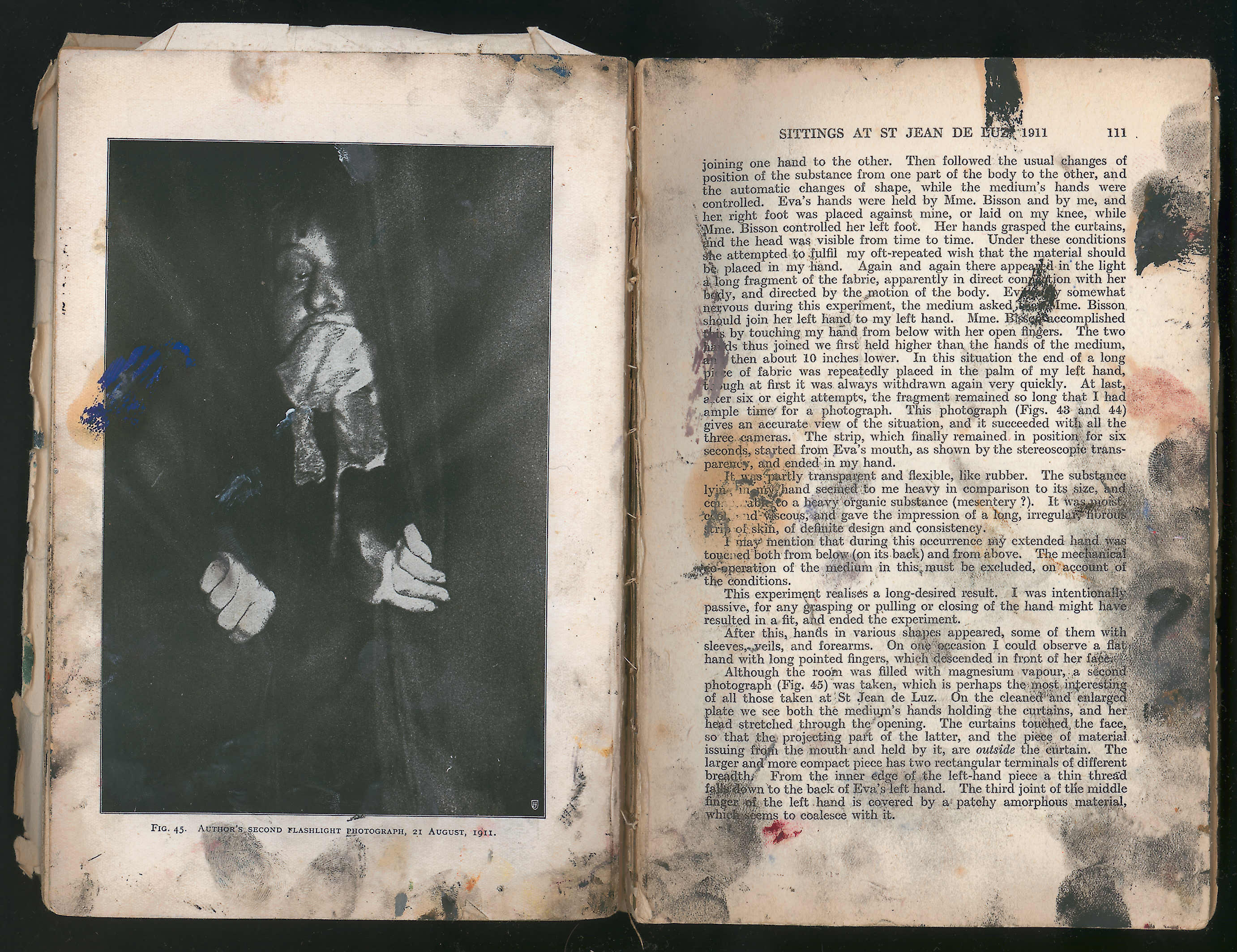

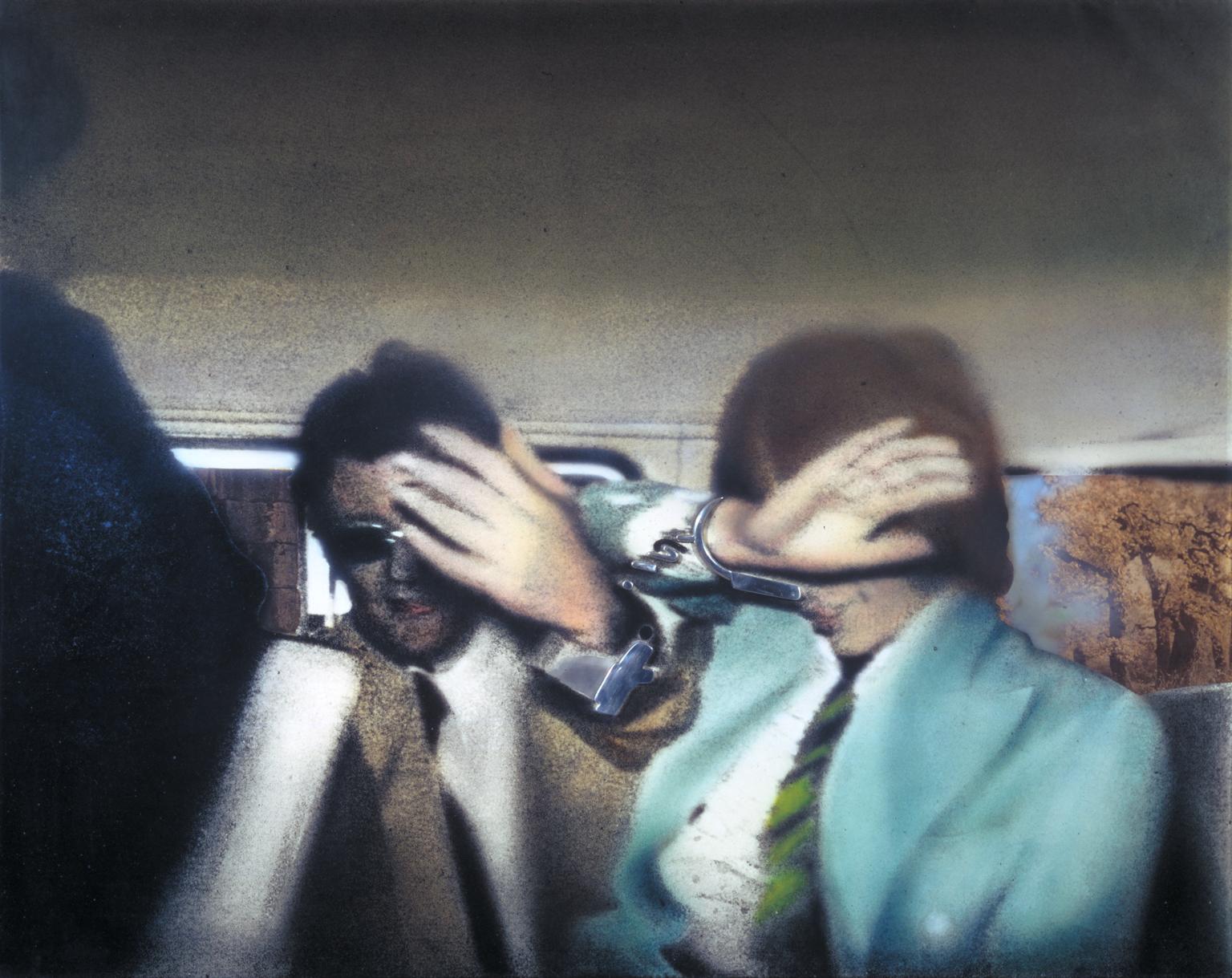

Fumai used her voice to great effect in her work, frequently dictating manifestos and statements to camera. Now her speech echoes throughout these galleries: from the basement one hears fragments of Valerie Solanas’s ‘scum Manifesto’ (1967), while the phrase, “Is there a spirit there? does it wish to communicate?” echoes from the upper floors. This idea of mediumship is a recurring trope; Italian medium Eusapia Palladino is invoked in a number of works, and indeed Fumai’s entire oeuvre could be read as an exercise in channelling. She made herself a vessel for voices she felt we all needed to hear, a transmitter motivated by a desire to foment change. In emulating the practices of spirit mediums, Fumai sought to create a scenario in which traditional modes of author- ship were altered and expanded. Her engagement with esotericism was motivated by a desire to transcend and resolve inequalities and injustices that beset our current condition. Accordingly, she drew not only from these occult traditions but also from the histories of radical feminism and Marxism; figures such as Ulrike Meinhof and Carla Lonzi are summoned directly via incantatory quotations.

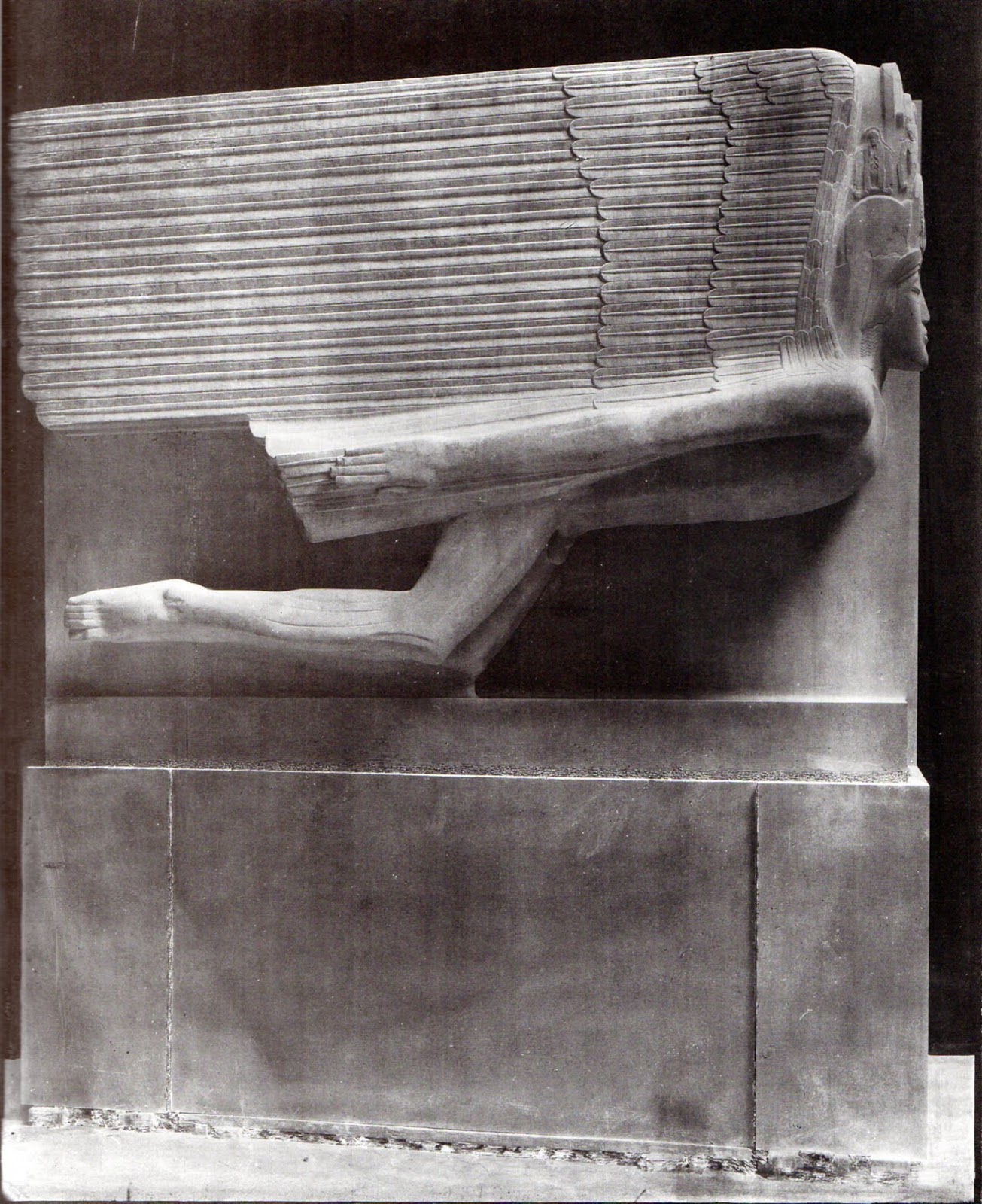

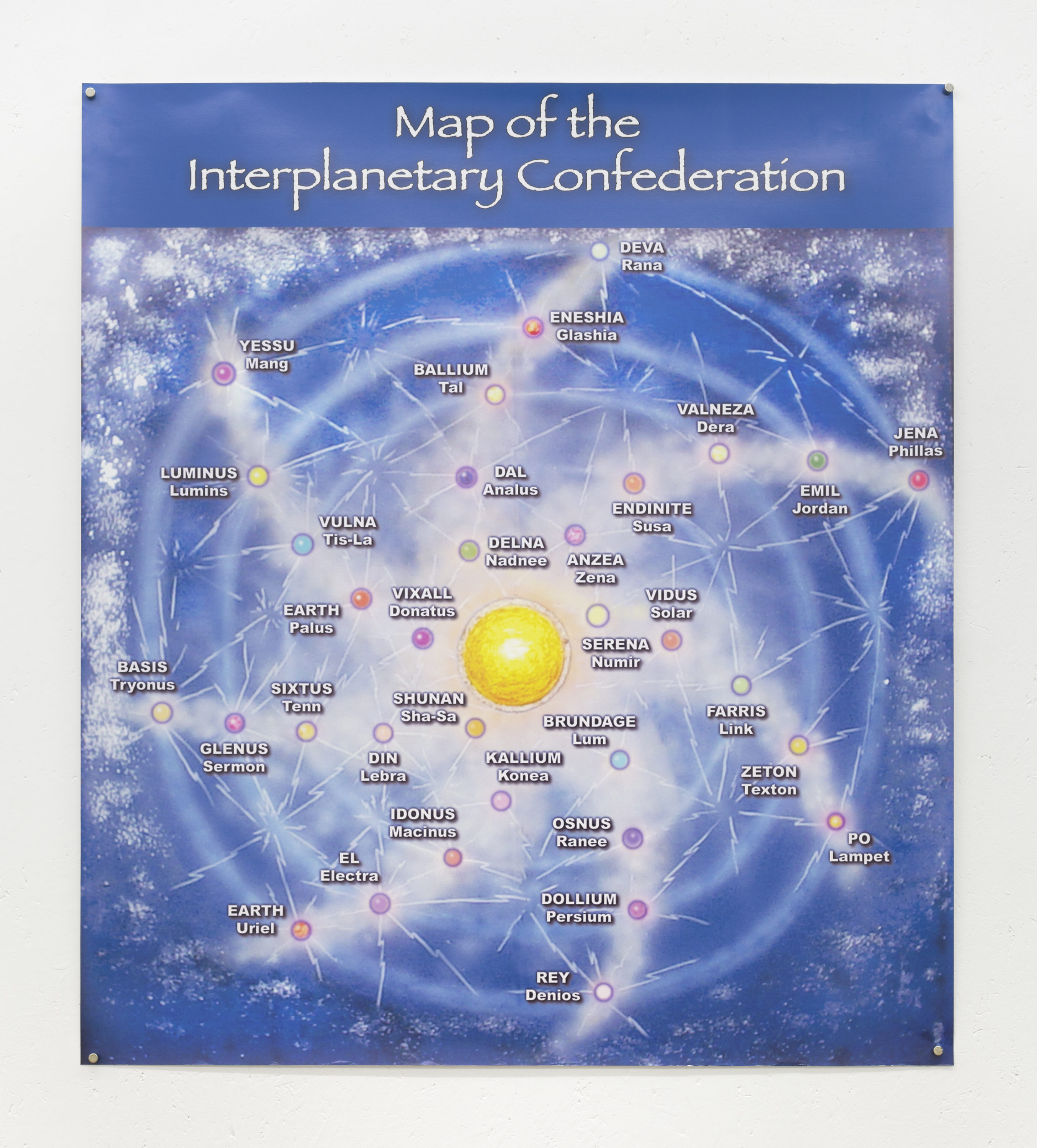

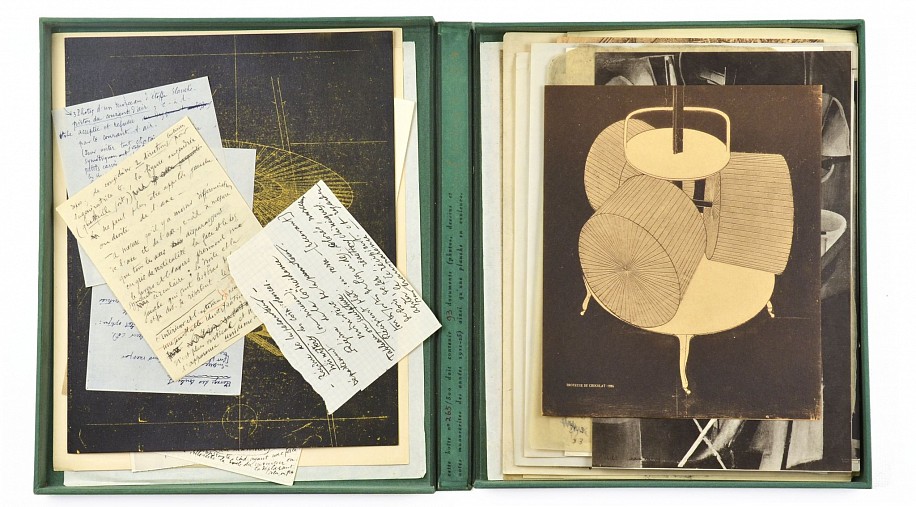

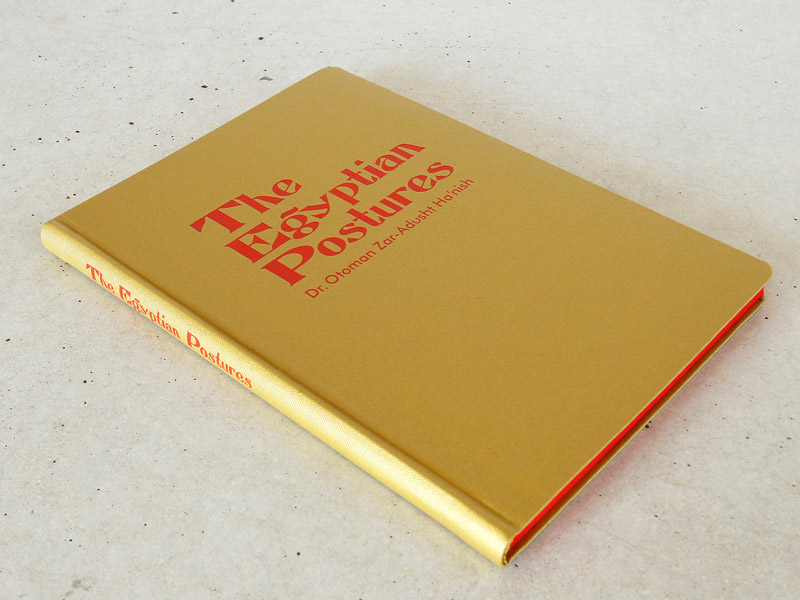

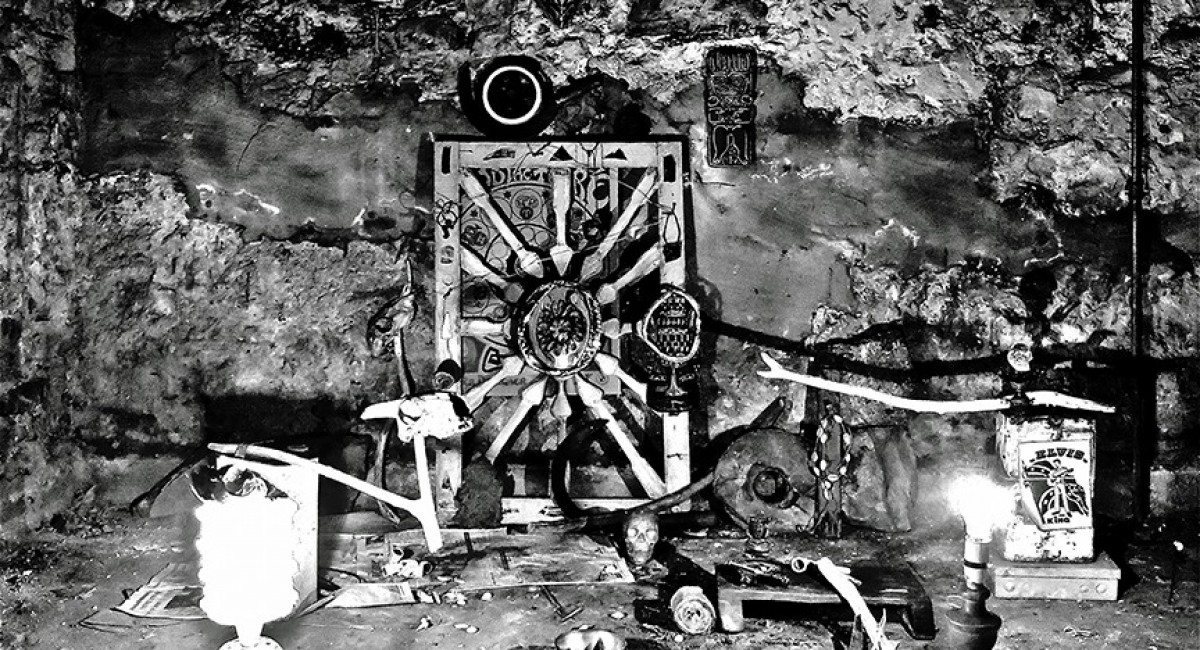

In coupling these diverse sources, Fumai created a dense but potent body of work that celebrates the legacies of women who have come to represent feminist empowerment. Using the conduits of cultural production, she resurrected, reworked and recirculated these legacies. La Loge – a former masonic temple dating from the 1930s – is obviously an apposite location for this exhibition. The interior is embellished with occult symbols, some of them echoed in Fumai’s own work. Real and fictional initiatory orders feature prominently in her oeuvre, as demonstrated in There Is Something You Should Know (2010–11), a mise-en-scène of liturgical equipment installed on the empty dais of the temple where ceremonies once took place. These props were used by Fumai in initiatory actions relating to an imaginary sect she conceived as an homage to filmmaker Jack Smith called sis (Scuola Iniziatica Smithiana); the piece feels especially poignant in that, until recently, it was not a discrete artwork but rather a selection of objects sporadically activated through performative rituals. Fumai’s death has altered the status of this collection, and now endows them with the aura of relics. In the case of a prematurely departed artist, hagiography becomes inseparable from material legacy, and it is impossible to interpret artistic legacy without recourse to biographical detail. Now all Fumai’s art is suspended at a twilight juncture, brimming with promise yet perpetually locked in a terminally unresolved state.