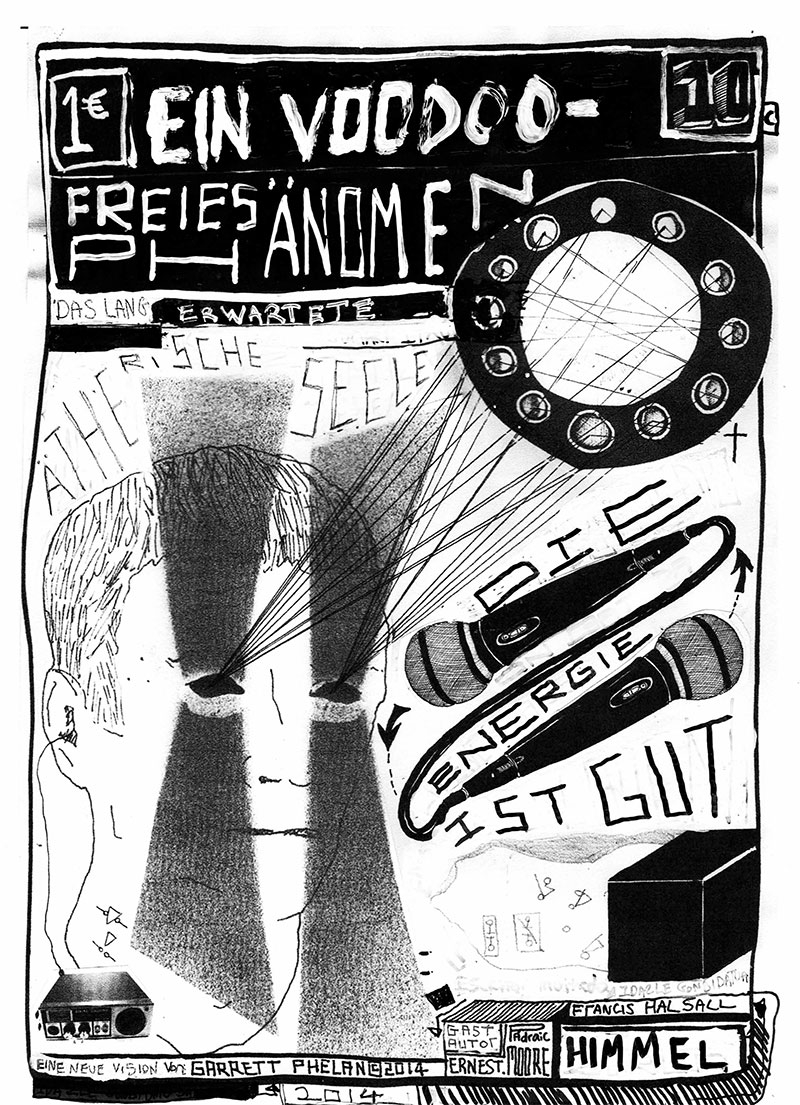

Preachers, Puppets, Pigs

I first saw A Sod State when it was screened at a cinema in Amsterdam in the autumn of 2022. Apart from myself and a handful of others, the audience that night was comprised predominantly of Dutch millennials. Inevitably, not everyone in attendance grasped every reference in the film, many of which refer specifically to facets of internecine conflicts in Ireland. Yet, this didn’t matter, for one of the strengths of A Sod State is that an in-depth understanding of all the complex issues it grapples with is not a prerequisite for engaging with it.

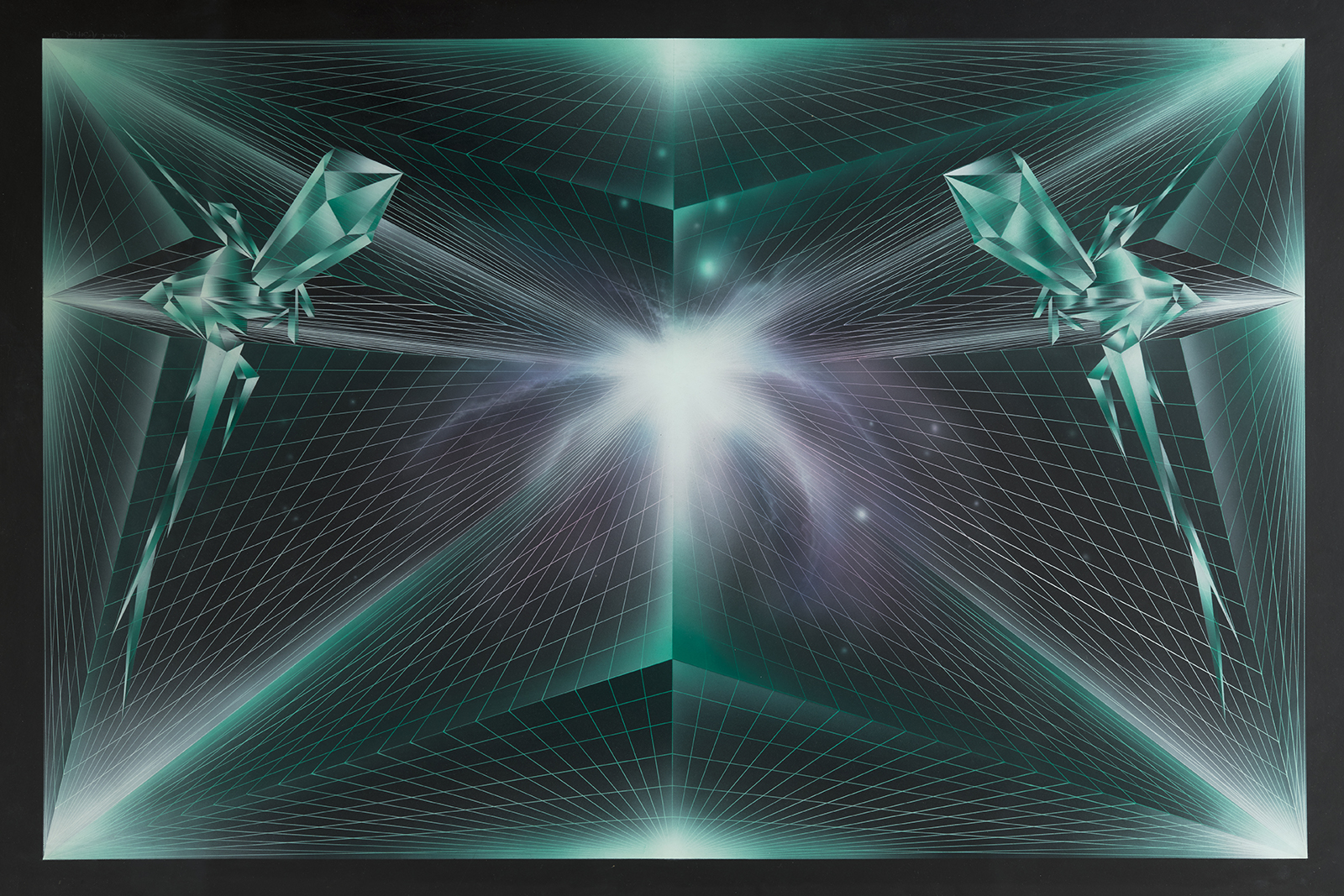

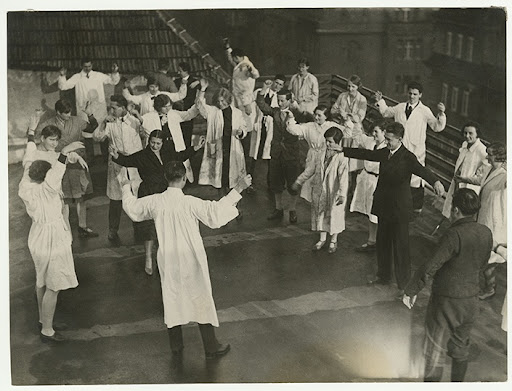

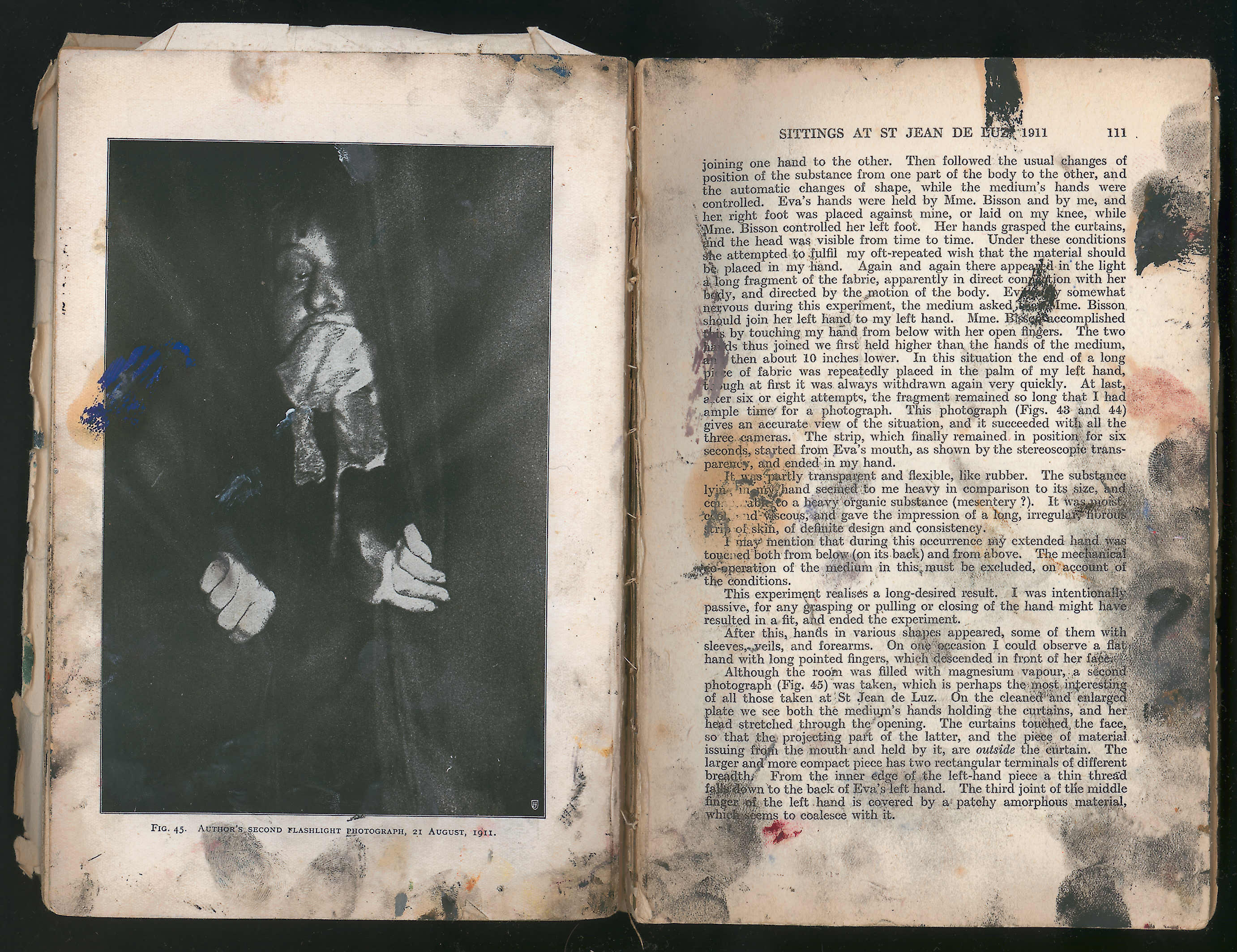

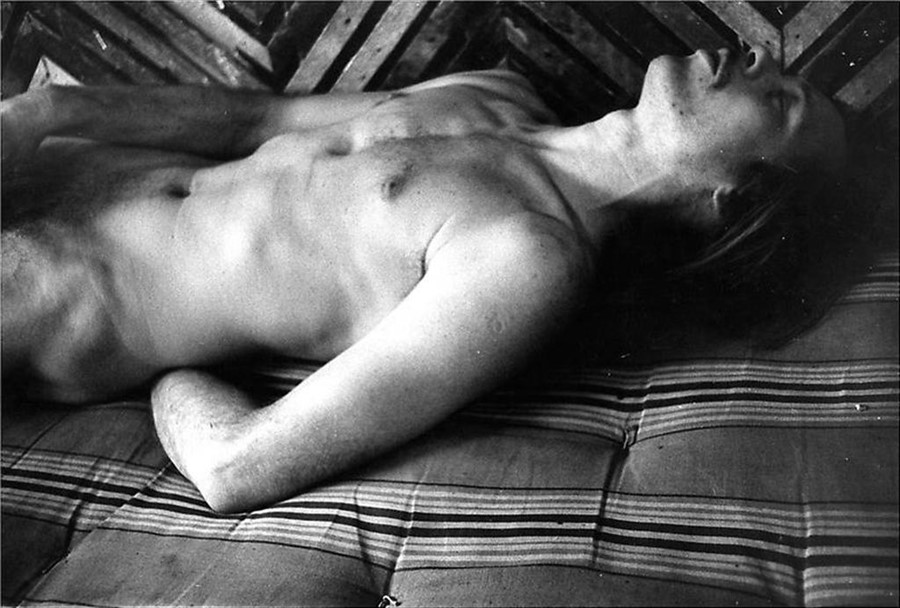

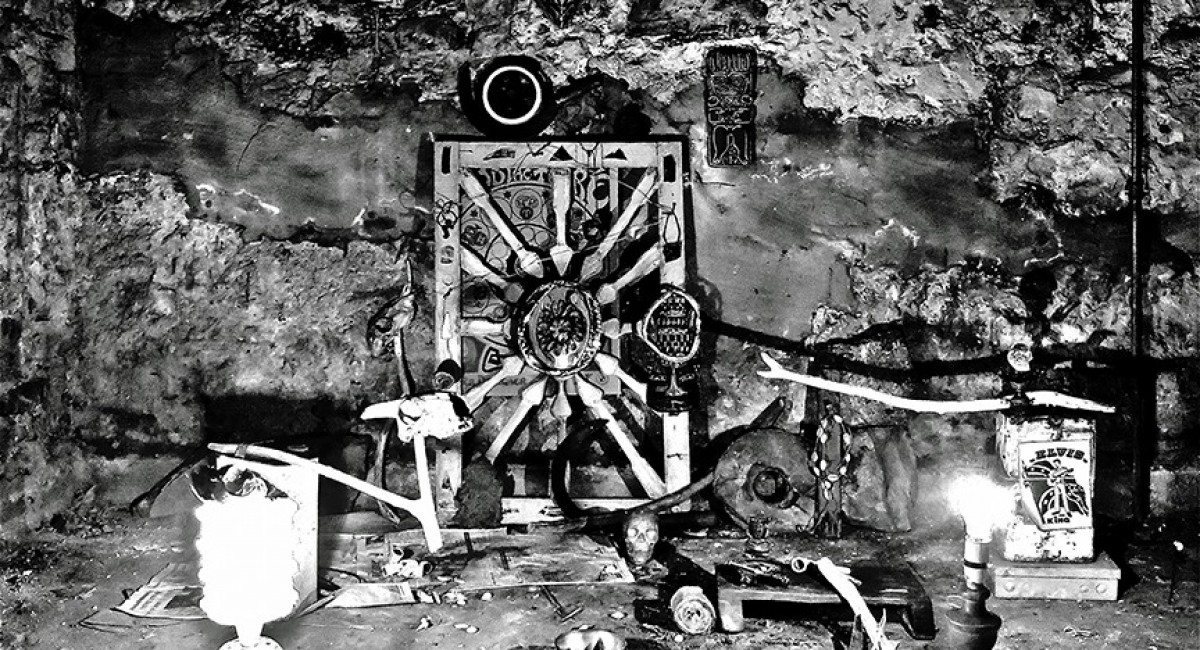

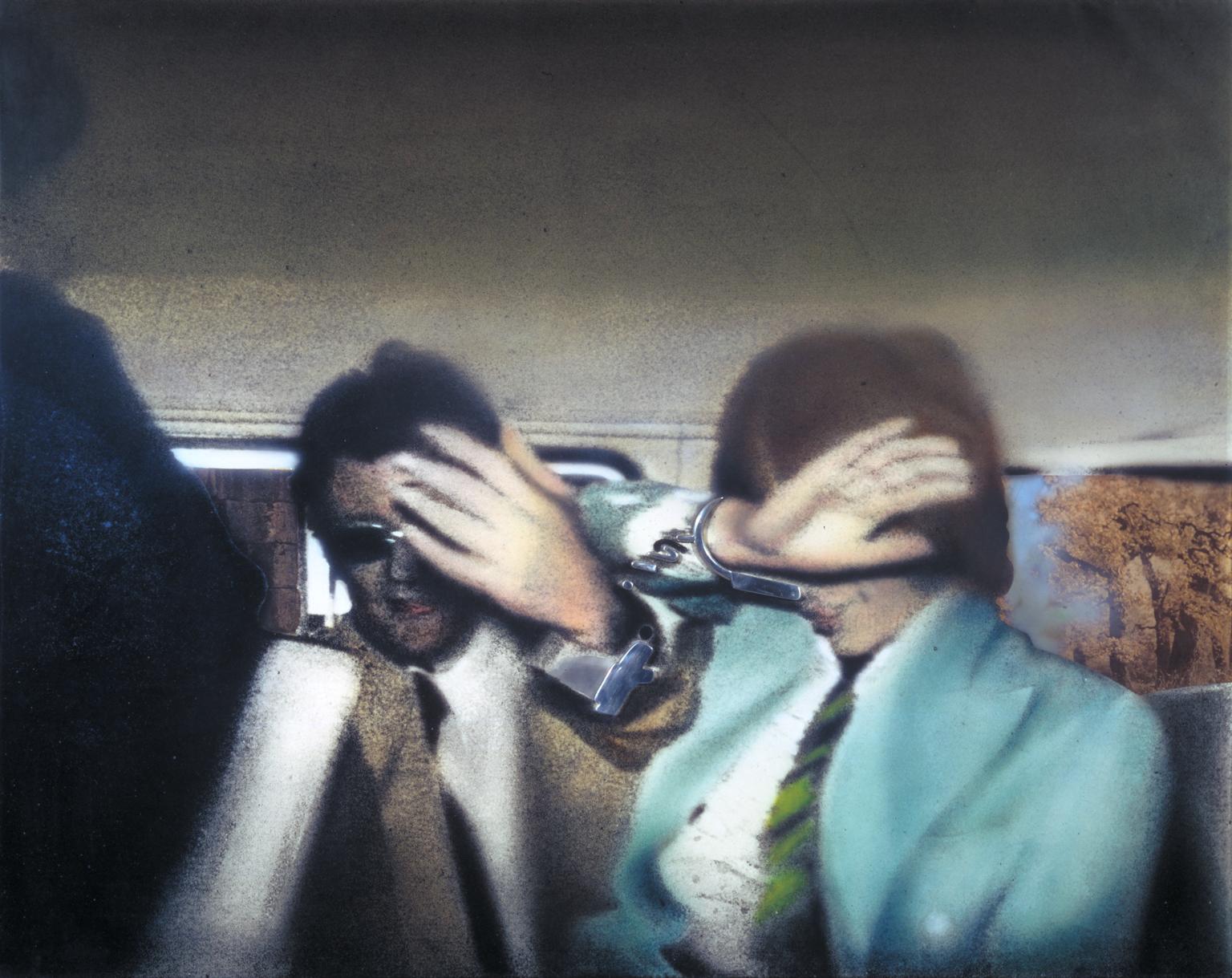

At its core this film is essentially an exploration of universal subjects: religious conflict, state power, the psychological consequences of war, the inheritance of hatred. A tone of unhinged menace pervades A Sod State that resonates with our post-plague era. Ryan makes us watch things that that lurk on the dark side of human consciousness: crucifixions, pig-faced beings, and bodies wrapped in plastic. We see cursed images from the very recent past: Gardaí participating in the Jerusalema dance challenge, a queasy merging of authority and entertainment, propaganda embraced by euphoric screen spectators.

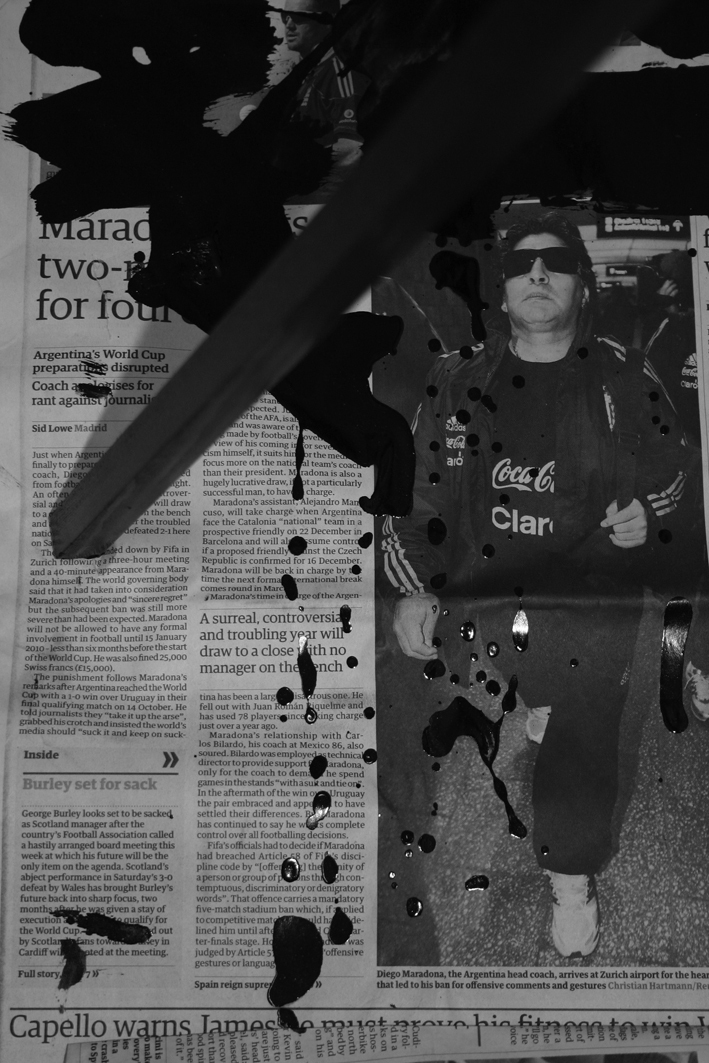

A Sod State continues to be appreciated by a wide audience but there’s no doubt that viewing the film in Ireland elicits a more acute set of responses. The context in which any artwork is encountered influences how it is perceived and understood. A Sod State possesses an added potency here, evoking, as it does, local incidents and issues. The film came together during the resumption of turbulence in Northern Ireland. The first screenings took place the same day that jail sentences were handed out to those involved in the shooting of the journalist Lyra McKee during rioting in Derry in 2019. The forced tugging of Northern Ireland out of the European Union (despite the fact that most people residing there had voted to remain) had numerous unintended, unforeseen consequences. A Sod State includes footage of loyalist youths throwing projectiles at members of the Police Service of Northern Ireland (PSNI), ostensibly protesting at the possibility of a border being delineated in the Irish Sea.

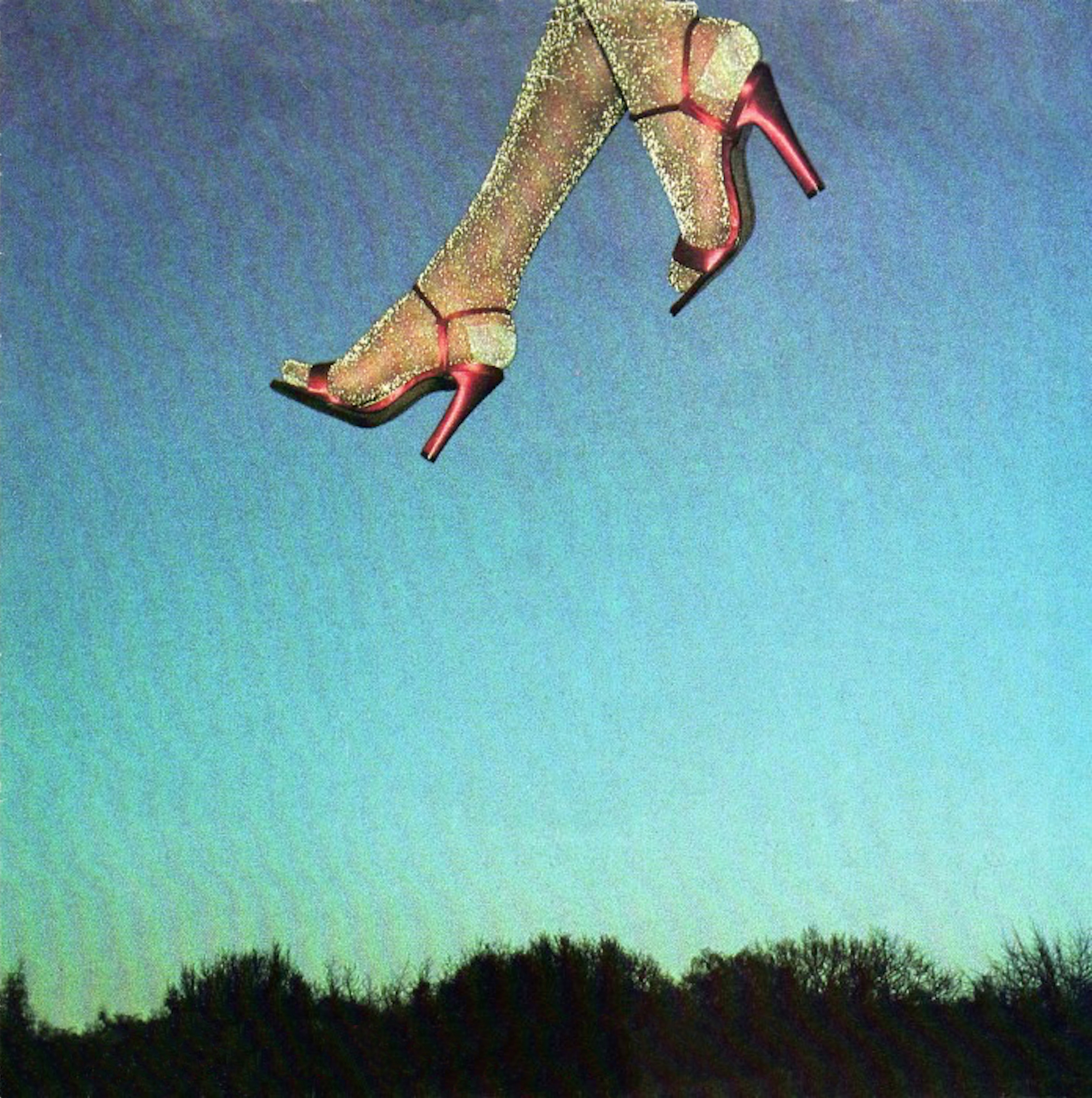

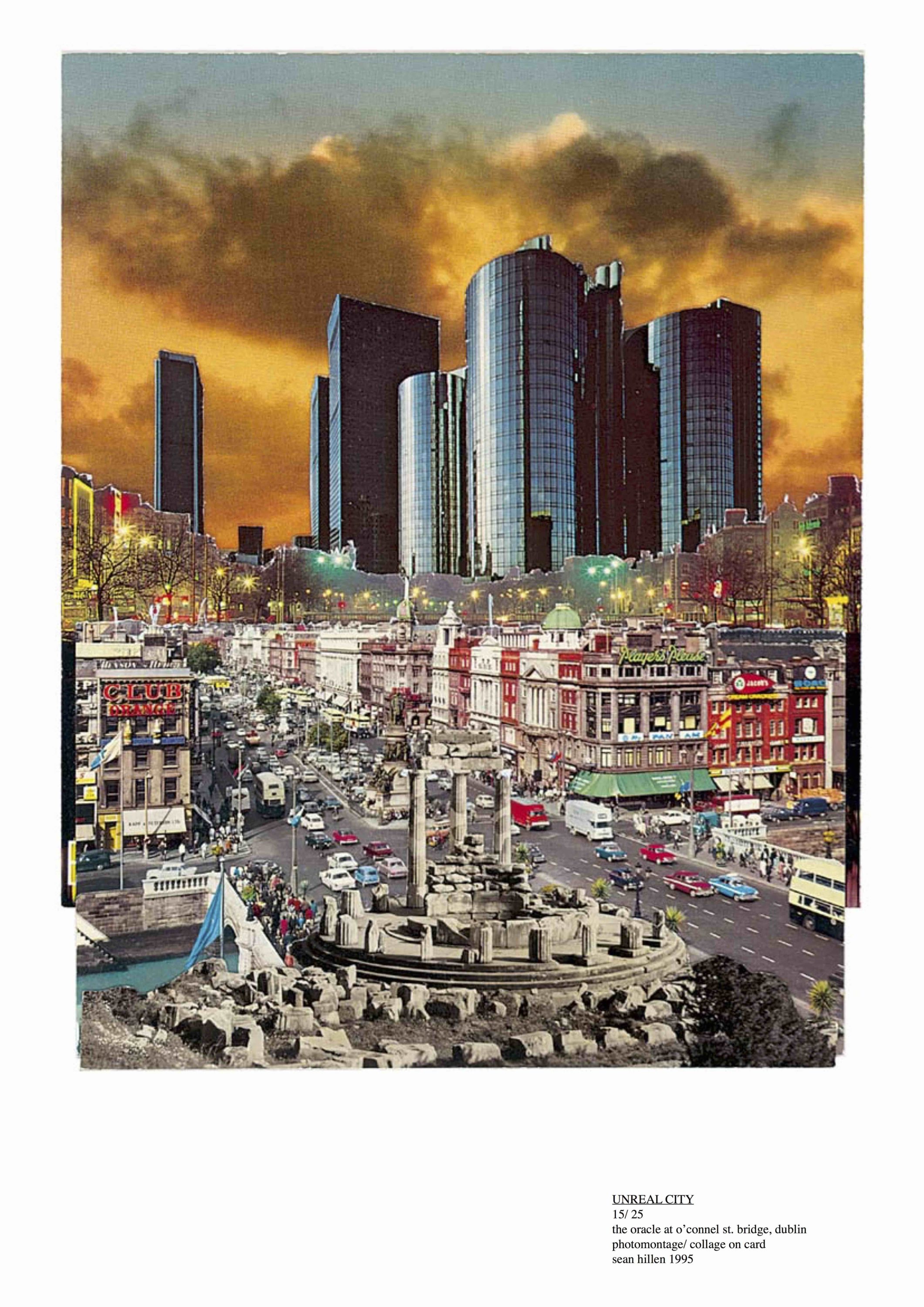

The first presentation of A Sod State in Dublin in April 2024, opened just weeks before the 50th anniversary of the Dublin and Monaghan bombings, in which thirty three civilians and an unborn full-term child were murdered by the Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF). (1) The warehouse space where the installation was exhibited is less than fifteen minutes from three of the locations where car bombs exploded on the 17th of May, 1974. Hundreds of witnesses – many of whom were gravely injured – recall body parts littering the pavement of Talbot and Parnell Street. On the other side of Dublin, near the National Gallery another car bomb exploded, killing a 21-year-old woman. Several photos show her body on the pavement next to the wreckage of burnt out cars; her platform boots protruding from a blanket. (2) A mute but palpable violence infuses this and other images taken in Dublin that day. (3) The images of broken people, cars, and buildings emanate a frozen horror. These images evoke the line from J.G. Ballard’s 2003 novel Millennium People that the “terrorist bomb not only kills its victims” but also “forces a violent rift through time and space, and ruptures the logic that held the world together”. (4)

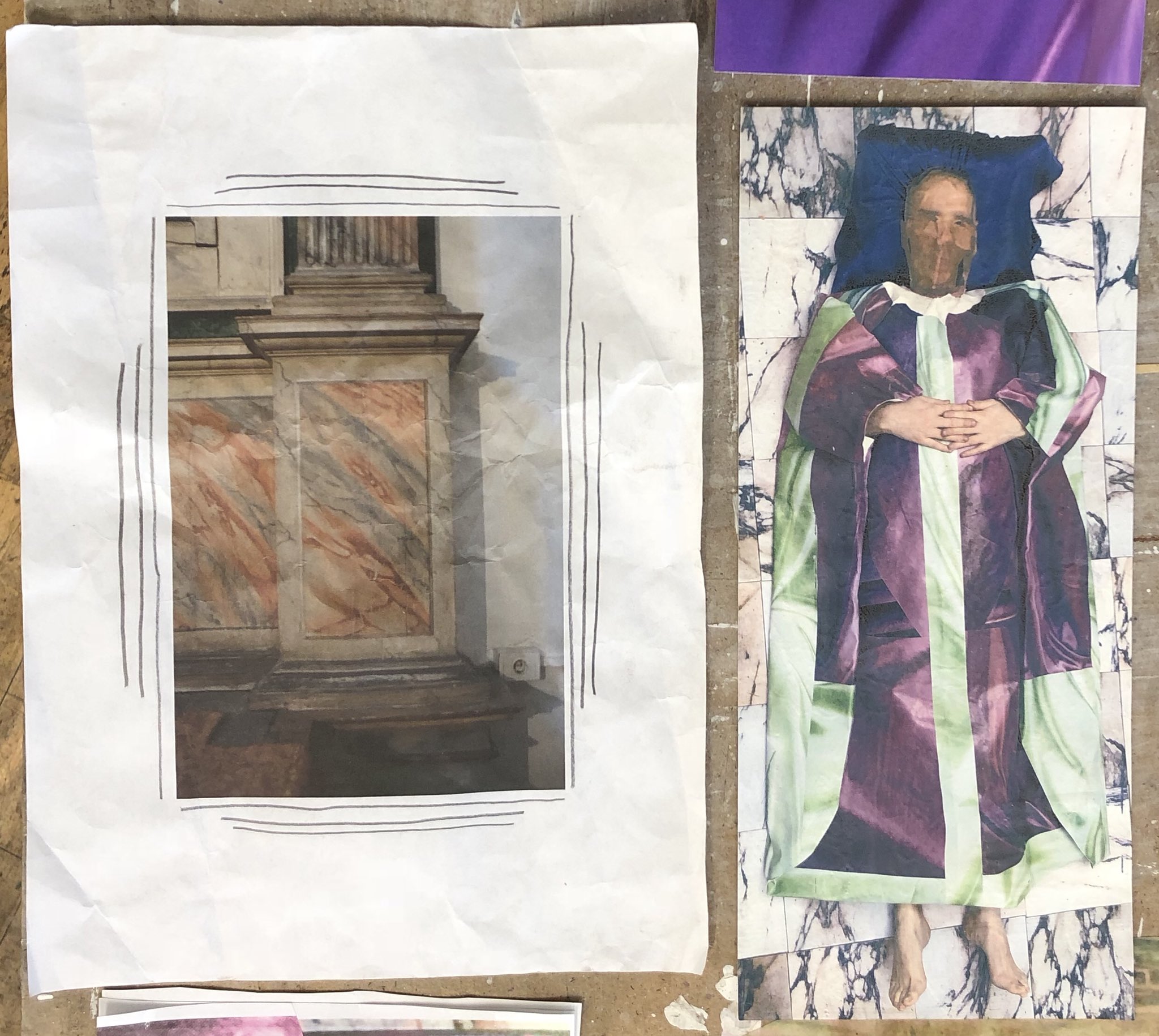

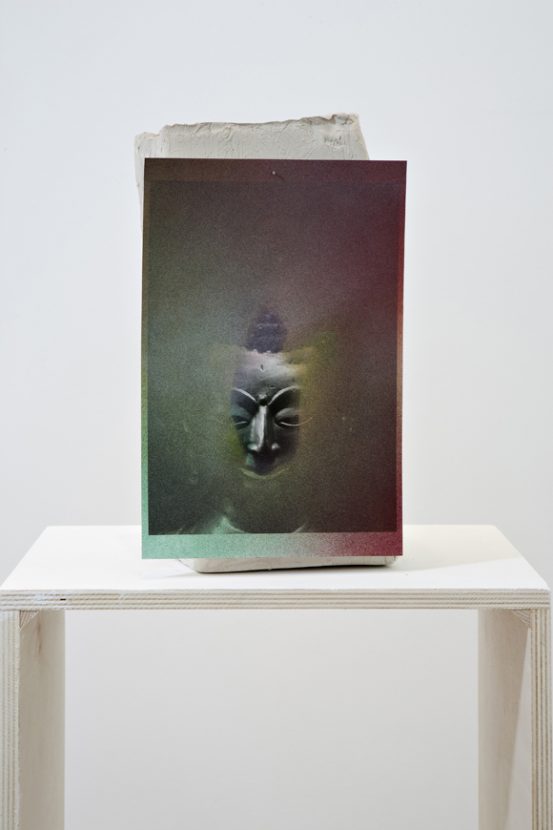

Ryan’s film is a study of visual vocabularies that define recent Irish history, in particular the aesthetics of sectarianism. One image prominently featured is that of the infamous UVF mural depicting two armed paramilitaries in balaclavas alongside the motto “Prepared for Peace, Ready for War”. At another moment in A Sod State we see Jacques-Louis David 1785 painting Oath of the Horatii. Ryan has essentially created a lineage of images that are at once art and agitprop. David’s painting is cast as a progenitor of the anonymously painted UVF mural; both artworks heroicising brotherhood, self-sacrifice and, ultimately, death.

The film opens with footage of Ian Paisley from the summer of 1966. A consistently bellicose presence throughout decades of bloodshed in Ireland, Paisley fused inflammatory political rhetoric with religious zealotry, as illustrated in his 1970s campaign to “save Ulster from sodomy”.

The year this footage was filmed Paisley was awarded an honorary Doctorate of Divinity from a Bible College in South Carolina where he also received training in deportment and public speaking. Ryan’s treatment of this material serves to highlight how affected and theatrical Paisley’s evangelism was. The preachers he encountered during his time in the American South influenced Paisley’s bombastic style. But in forging his own mode of TV charisma Paisley was also undoubtedly influenced by the rock stars of the period; he became Ulster loyalists’ answer to the Swinging Sixties.

If Paisley is one of the central entities of A Sod State, then another is the older Irish male with a slight Limerick accent whose voice and face punctuates the film. This is the artist’s father; a frequent collaborator who has contributed significantly to several bodies of work over the past fifteen years. (5) Ryan’s aim in interviewing his father was to tap into and transmit the trauma he experienced as a citizen of Ireland during the mid-70s to the late ‘80s. Many people living in the Republic during this period actively blocked out the magnitude of what was occurring in close proximity. It was as though they entered a state of disassociation, en masse. Ryan’s father was clearly impacted by the Troubles; his personal accounts of the conflict run throughout the film. He speaks of the scars of his “mental afflictions” and how there was no way of detaching from the psychic fallout of terror; how “it was a situation on TV all the time; it was a television war”. A Sod State draws heavily from found TV footage, reflecting on the fact that the great majority of people in the Republic experienced the realities of what was occurring elsewhere on the island via the TV screen. (6)

Aside from Paisley and the father, the other entity we meet here is the puppet. Its opening line, “we live together in trying times”, is followed by the truism that “whatever side you’re on, you only know half the story”. Like dolls, mannequins and automatons, puppets are infused with an inherent uncanniness. This stems not only from their apparent sentience, but also the uncertainty as to what or who animates them and the question as to who is speaking through them. The puppet in this film is a mouthpiece for multiple persona. In its monologue, it states how it is, amongst other things, a “Red Army Faction, a feminist, a priest, a politician” capable of travelling through time and occupying different historical episodes. This entity is not unlike the protagonist of the Rolling Stones song that features so prominently in the film who: “stuck around St. Petersburg”; “rode a tank” and “held a general’s rank and shouted out: Who killed the Kennedys?”

Sympathy for the Devil is just one of several popular pieces of music that are key ingredients in this film.(7) It is coupled with Some Say the Devil is Dead, which was popularised in the ‘90s by the Wolfe Tones, but originates much earlier and features references to the Book of Revelation.(8) Rebel music balladeers, the Wolfe Tones have courted controversy frequently over the decades. In 2023, former Taoiseach Bertie Ahern made a public statement that young people should educate themselves on the ‘ferocious trauma’ of the Troubles after crowds chanted “Ooh, Ah, Up the RA” during a Wolfe Tones performance at a major music festival.(9) Twenty years ago, the Wolfe Tones were at the centre of another cause célèbre, when Aer Lingus were forced to remove republican songs from their trans-Atlantic in-flight entertainment. This was in response to Ulster Unionist Assembly member Roy Beggs Jnr’s complaint to the airline of what he branded the “blatant promotion of militant, armed republicanism” on a flight from Dublin to Boston.(10)

In a 2013 interview in An Phoblacht, whilst discussing his work Fragmens and the 1981 Hunger Strike, (11) Irish artist Shane Cullen stated how in the early 1980s “everybody in Ireland went through a trauma (…). It wasn’t until about ten years later that I felt skilled enough as an artist to be able to address such an important event. It took that long for me to feel I could deliver a work that could do it justice and address it properly, in a very public way. I wanted people to recall that time”. (12) A Sod State contributes further to the canon of what has come to be known as Troubles Art. But Ryan, who was only eleven years of age when the Good Friday Agreement was signed in 1998, revels in raw material pertaining to the Troubles in a way that was perhaps not possible for those who experienced the atrocities first-hand. His work bears none of the forensic, clinical detachment of his predecessors. Instead it is all about about sensation and addresses these ideas via fragments of pop culture.

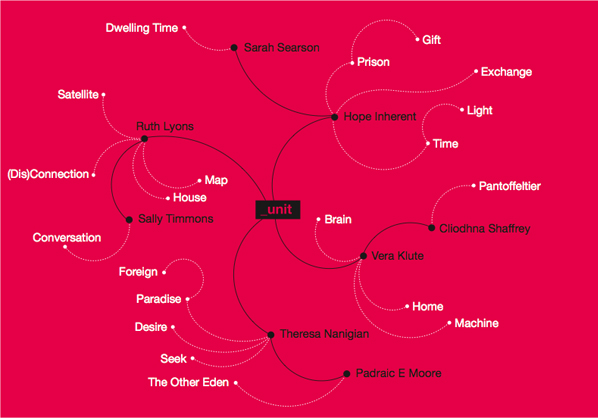

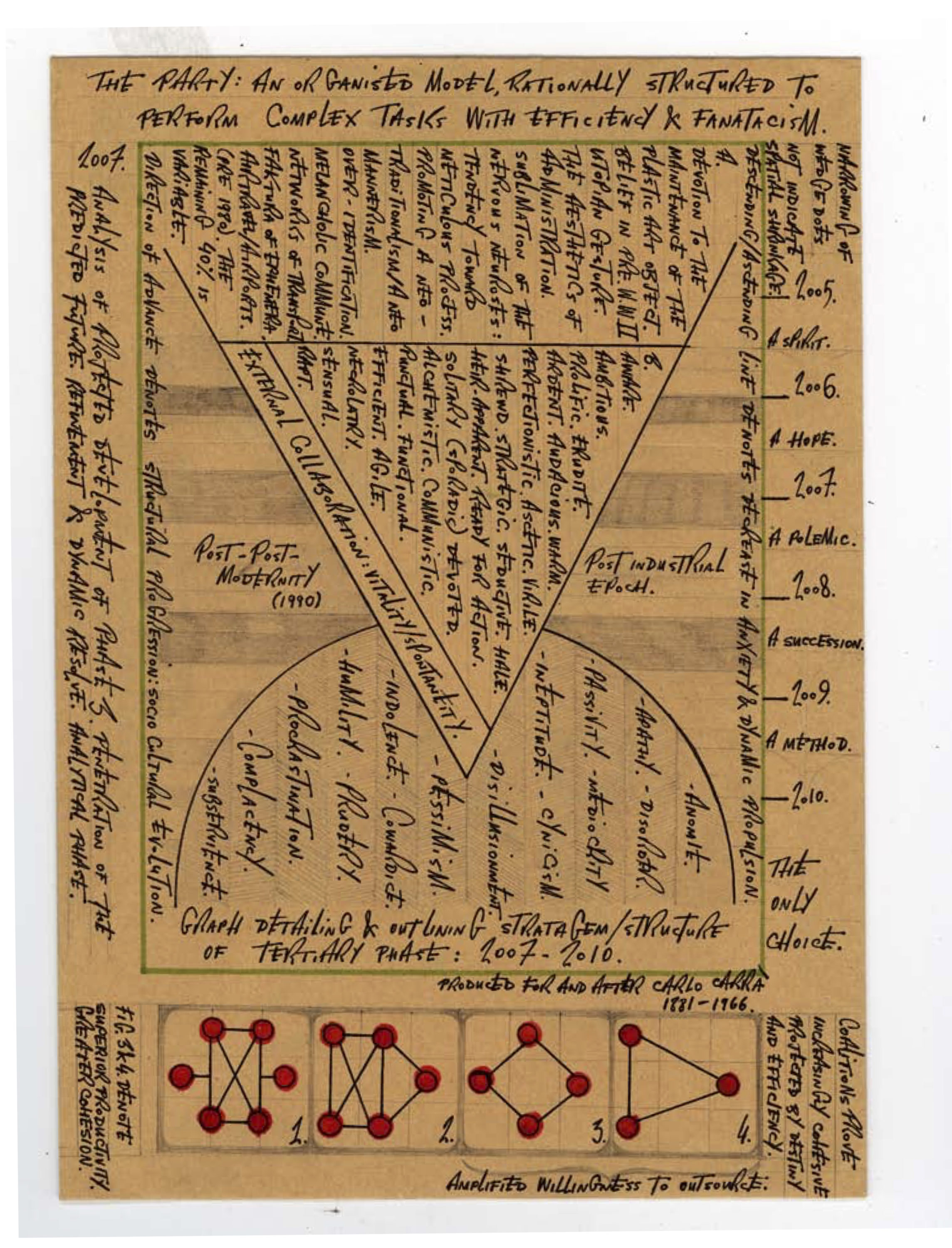

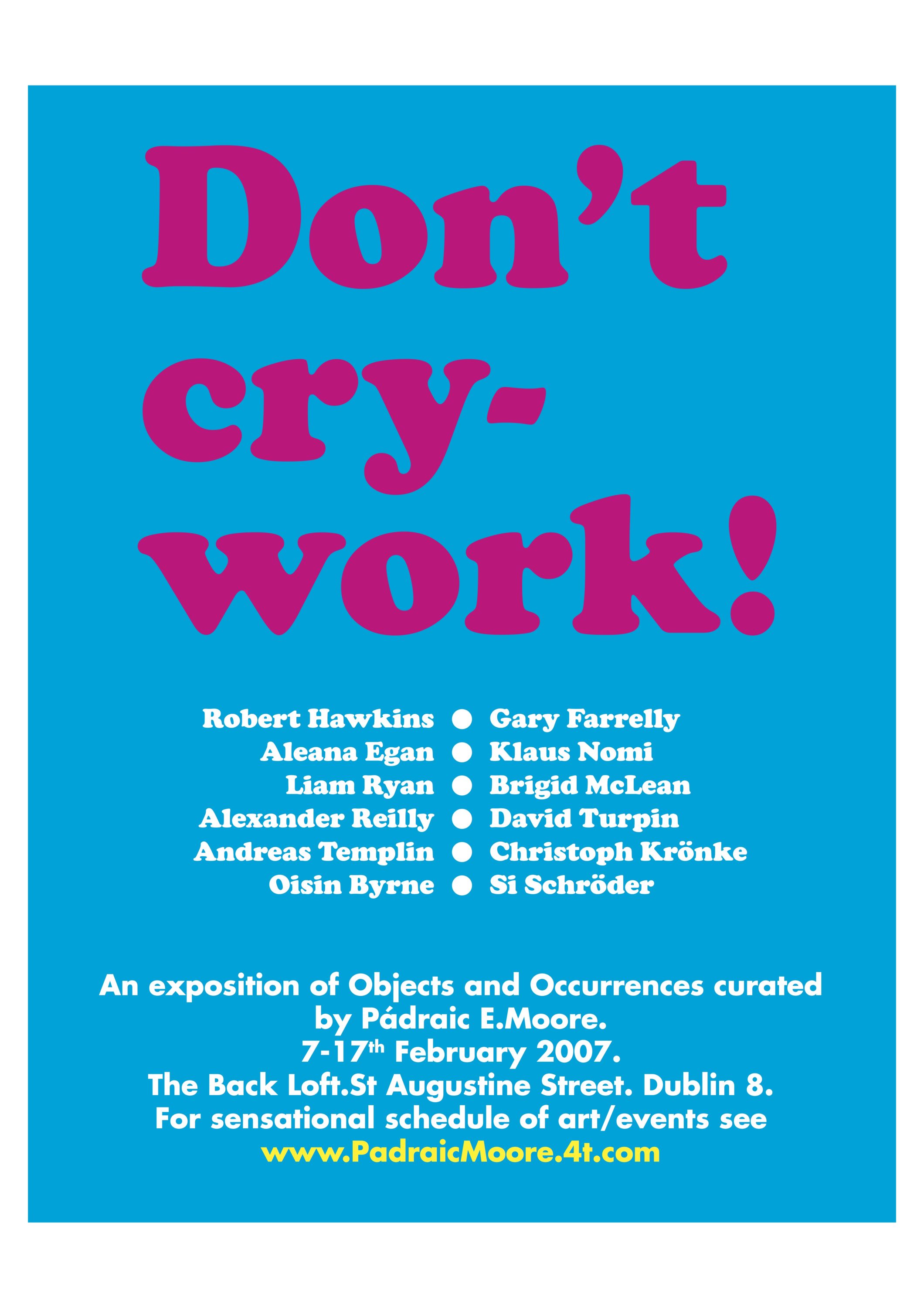

The past decade has seen the emergence of a new generation of visual artists directly addressing the psychic and political ills of contemporary Ireland. Born in the final decades of the last century, this cohort – of which Ryan belongs – tackles intertwining, seemingly interminable issues. Coming of age during a period of relative optimism and prosperity, precipitated by the Celtic Tiger and Peace Process, these artists also witnessed and watched prospects change with the economic recession, and the calamities that followed. While not operating as a unified front, this new wave diagnose the state of our nation today. (13) Much has changed for the better over the last four decades. But these artists highlight how decolonisation remains an unfinished process; how landlordism continues to strangle the populace and how spectres of unresolved grief are never too far away. “The Times They Are a-Changin” but Ireland remains the “old sow that eats her farrow. (14)

[1] In 1993 the UVF admitted responsibility for the Dublin and Monaghan bombings.

[2] Carey M. and Carroll L. “Justice Time for Dublin/Monaghan Families”, Irish America Magazine Online, February/March 2004. https://www.irishamerica.com/2004/02/justice-time-for-dublinmonaghan-families/

[3] A collection of almost 150 uncredited images of the aftermath of the Dublin bombings of May 1974 are available online via Dublin City Council: https://www.dublincity.ie/library/blog/dublin-bombings-1974

[4] J.G. Ballard, Millennium People (London: Flamingo, 2003), 182.

[5] The proximity of Ryan’s father to himself and his work has been something the artist has utilised to various degrees for the last fifteen years through performance, film, and an extensive accumulation of images. For Ryan, it is a way of both understanding and exorcising their relationship through art production.

[6] From the late 1960s onwards footage of violent spectacles, now viewed as pivotal events, was frequently televised. This is exemplified by the attack on mourners that took place in March 1988 at Milltown Cemetery in Belfast and the events that followed.

[7] Others include a rearranged version of Enya’s Orinoco Flow (1988) and Orbital’s Belfast (1991).

[8] The lyrics “Six o’clock, six o’clock, six o’clock etc.” are a reference to the Number of the Beast being given as 666 in Revelations 13:18.

[9] The phrase originated as an expression of support for the IRA. Ahern was one of many who argued that the band were ‘romanticising’ the IRA and the Troubles after they performed at Ireland’s Electric Picnic.

[10] The politician wrote to Aer Lingus complaining how “in the current climate of international terrorism, “it was the same as “the speeches of Osama Bin Laden being played on a trans-Atlantic Arabian airline”. See: “Wolfe Tones pulled from Aer Lingus flights”, Irish Examiner, 24th March, 2003, https://www.irishexaminer.com/news/arid-30092926.html

[11] Shane Cullen’s Fragmens sur les Institutions Républicianes IV consists of ninety-six large panels, onto which have been transcribed in paint the contents of the numerous communications smuggled in and out of the H-Block prisons in the 1980s.

[12] “To be terrified of your own history is not a good thing”, An Phoblacht, 3 February 2013. https://www.anphoblacht.com/print/22692

[13] Just two of the others included in this cohort are Jesse Jones and Eimear Walshe.

[14] James Joyce, A Portrait as the Artist as a Young Man, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000, 203.