Seeker

Theresa Nanigian’s seeker provides all those who engage with the project with opportunities for contemplation (focused and open ended) via written and spoken conversational exchanges (1). Comprising of several facets, the total magnitude of Nanigian’s contribution can only be inferred from this publication, which constitutes its crystallisation. Perhaps the most significant facet of the processes which seeker entails involved the artist meeting and interviewing individuals unified purely by their status as non-nationals residing in Portlaoise – a context in which the socio-political issue of EU- nationals and asylum seekers immigrating is particularly contentious (2).

Focusing upon this cohort was strategic in presenting an atypical portrait of the microcosm of an Irish town that has, like so many, undergone significant and dramatic change in recent decades. In addition to Nanigian’s inference that these individuals are as worthy as any to represent the town in which they reside, an additional relevance to the artist’s focus on this group derives from the dissolution of the prolonged spell of fiscal confidence that began in the 1990s. While the consequences of the downturn are widespread, the marginalised and disenfranchised are invariably most adversely affected. Economic recession is merely one of many difficulties non-nationals in Ireland must confront since the perceived scarcity of opportunities within the new economic climate can be directly linked to a potential escalation of intolerance, racism and bigotry.

The generation of meaning through the juxtaposition of seemingly contradictory situations, propositions and idioms is a recurring characteristic of Nanigian’s work. In seeker, this is exemplified through the close coupling of austere statistical data (a principal ingredient throughout Nanigian’s practice) with data of a more personal nature, gleaned from responses to the Eden questionnaire utilised by the artist (3). Coupling cold statistics (many of which are rather bleak) with idiosyncratic information reveals vantage points that might otherwise have gone unnoticed. When contrasted with the ‘personal’ data the unstable authority of the stats becomes apparent as dissimilarities between the two modes underscore how demographic language can dehumanise those to whom it relates. This example highlights Nanigian’s concern with exposing how quotidian structures – in this case the language that we use on a daily basis – are imbued with ideological meaning transmitted and inculcated so subtly as to be almost subliminal. However, her idiosyncratic deployment of the aesthetics of administration (4) also illustrates, paradoxically, how such idioms may also be utilised to the opposite effect and infused with singularity. Equally deft is Nanigian’s simple yet strategic tactic of abstracting the contextual frame and expanding the relevance of her project by making the local and nationwide conterminous. By blending information gleaned from individuals with nationwide statistics, Nanigian ensures local specificity is maintained but balanced with information of a more universal significance. This move counters the risk that seeker might be interpreted as relating exclusively to Portlaoise; a misreading that could obscure the fact that many of the matters raised are pervasively ubiquitous.

Though no claims were made that the lives of those participating in seeker might somehow be improved or enhanced by their engagement, the work was conceived with altruistic intentions evident in the reciprocal nature of its process. Individuals were presented with the pretext to envisage their dream of Eden and, in so doing, provided Nanigian with the material required to develop her endeavour. Throughout, the various participants’ dreams of Eden permit insight into the lives of others that may incite a reappraisal of the viewer’s own perspective. Reading these responses accentuates the fact that the label of non-national that each of these unique individuals has been given, casts them all in a somewhat negative, inanimate light. Moreover, the responses to the questionnaire – most of which depart from the regimented format of questions, draws attention to how the urgency and necessity of the search undertaken by the majority of those who responded to the seeker questionnaire is more challenging and indeed perilous than that undertaken by most of those who will read this ensuing publication. That Nanigian decided that the most suitable trajectory for this work should be a publication – available to be accessed and read in any place and at any time – emphasizes how, in terms of ideas and information presented, seeker was conceived to expand the impact and the audience amongst the local citizenry. The tendency to cultivate ties and provide participants with a juncture in which they could literally dream of Eden connects seeker to work previously executed by Nanigian and the cluster of methods she has employed thus far links her with several of her predecessors (5). However, though the legacy of conceptualism is certainly apparent in Nanigian’s work, its true subject is the convergence between contemporary art practice and ethnography.

Perhaps it would be accurate to position Nanigian’s practice as a permutation of what has become known as relational or dialogic aesthetics. Though it is not my wish to dwell upon that which has so recently been hotly debated, it would be negligent to dis- cuss Nanigian’s project without acknowledging the turn toward an emergence (or re-emergence) of what Nicholas Bourriaud repeatedly defines as the increasing artistic impulse not “to form imaginary and utopian realties, but to actually be ways of living and models of action within the existing real (6)”. Instead of a discrete, portable, autonomous artwork relational art is bound to the contingencies of its environment and audience – a quality exemplified in Nanigian’s seeker project. Inserted into the context of living social relations, Nanigian’s work places these relations themselves in an integral position. Theresa Nanigian typifies the contemporary artist whose practice is based not so much upon creating data but assembling and rearranging it in order to make clear that which was less visible. For many artists the corollary of this process is the subordination of the actual production of aesthetic objects. By contrast, what makes Nanigian’s work so engaging and multi-layered is her resistance to such an eschewal of the material artwork. Every process and interstice (and in this case, every dream of Eden) is indexed in an aesthetically distinctive – and, in many cases, visually seductive – manner, confirming the truism that: “Without the idea there is no object but without the object there can be no idea (7)”.

- seeker is a component of Unit, an artists residency conceived specifically for Portlaoise town and surrounds. The project comprises of five artists and four curators applying different methods to investigate the diversity of both people and place.

- Nanigian intentionally included one exception in her pool of non-national participants an Irish national who became a seeker herself upon emigrating to the UK before returning home.

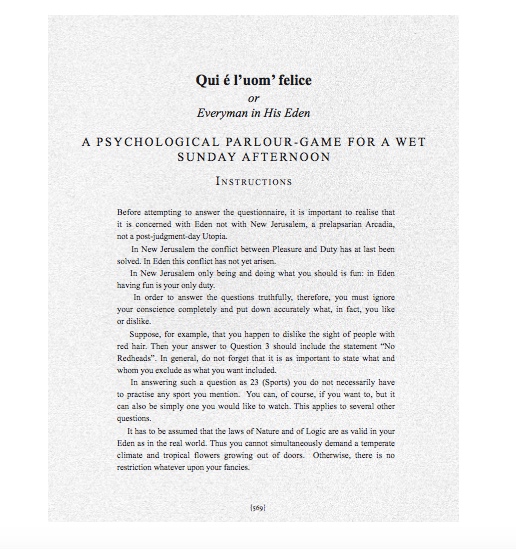

- In the case of seeker, Nanigian took as a framework not the type of questionnaire which one might encounter in the world of market research but rather a questionnaire titled “Everyman in His Eden” or a “Psychological Parlour-Game For A Wet Sunday Afternoon” devised by the poet W.H. Auden in which the individual is invited to consider and reveal their definition or dream of Eden.

- This term was coined by Benjamin Buchloh.

- Some of the methodologies implemented by Nanigian’s work evoke those developed and utilised in a number of projects realised by Douglas Huebler and Dan Graham in the late 1960s.

- Nicholas Bourriaud, Relational Aesthetics Les Presse Du Reel, France, 1998.

- Quote from Mel Bochner in conversation with the author, December 2007.