Slight Heat of the Eyelid

Like many cultural producers of the earlier half of the twentieth century, playwright Berthold Brecht developed tactics to interrogate and accentuate the artifice of the medium in which he was working. Brecht’s self-reflexive plays were formulated with the intention of disrupting an audience’s perception of the familiar in order to encourage a re-evaluation of reality (outside the theatre). A cursory comparison between Brecht’s work and that of Nina Canell is useful (in spite of the radical dissimilarities in their media and temporal contexts) for the way in which it illuminates aspects of Canell’s work that may otherwise be overlooked. In particular, the comparison accentuates Canell’s tendency towards a type of realism that relies not upon imitative verisimilitude but upon tactfully disrupting audience perceptions through an exposure of the inherently enchanting nature of things to which viewers may have become anaesthetised.

Though much has been written about the numinous, uncanny aspects of Canell’s work, it is worth noting that these qualities are almost always revealed as being the result of an everyday substantive, scientific phenomenon. Consisting of components and situations that make demands upon and activate the spectator, the objects she produces are not resolved but are instead ongoing, operative devices conceived to counter audience passivity, emphasising the value of dynamic alertness both inside and outside the gallery. Via what she terms ‘surreal-realism’ (2). Canell draws attention to the miraculous character of quotidian phenomena, revealing the marvellous within the mundane and discreetly exposing the nature of things as they are.

This cultivation of alacrity within the viewer is exemplified in Digging a Hole, a work produced collaboratively with Robin Watkins and installed in the anteroom that mediates between the external world and the main gallery space at mother’s tankstation. On first sight, the documentary footage of a solitary man shovelling into the earth, hollowing out a cavity in the soil at his feet, seemed a transparent depiction of manual labour. However, the potential of the symbolism of this vignette quickly became dazzling, while its location within a transitional space was revealed as strategic. The act of digging down into the earth results in the formation of a median point where antipodes exist simultaneously between above and below and light and dark, between that which is concealed and that which is exposed. This idea of a median point, conflated with the mystery regarding the motives of this digging man and the absence of any explanatory narrative, creates a provocative ambiguity that beckons one to construct subjective meaning from the elusive piece. One wondered if the hollow might be a grave or tomb, or perhaps instead a furrow in which seeds would be planted to cultivate new life. Was the act of probing into weighty darkness intended as a metaphor for the act of artistic production? Digging a Hole demonstrated how ostensibly irreconcilable categories, meanings and distinctions are often exposed – by the shallowest of excavations – as nebulous and fluid.

Throughout this show Canell’s predilection for denaturing prosaic, predominantly labour-related objects enabled an array of flotsam and jetsam – including buckets, basins and, surprisingly, a pair of white plimsoll shoes – to transcend their original functions and assume new metaphorical lives through their incorporation into indeterminate, idiosyncratic sculptural situations. This alchemy was especially apparent in Expand Expand, Through Bush and Land, a family of assemblages within the exhibition. Eschewing symmetry and a countenance of completion, this nomadic congregation of objects – installed as a ludic landscape – of this grouping precluded the possibility of a single central focus, inducing spectators to reposition themselves to discover previously obscured aspects. In addition to literally compelling the spectator into dynamic engagement, the multifaceted configuration comprising this sprawling piece evoked the notion that some mysterious experiment or scientific procedure was underway.This beta-test appearance was entirely apposite, considering that Canell’s practice is characterised by a proclivity toward sequestering commonplace materials ’as a way of making without adding to the world of objects.’(3) That thaumaturgic, transformative power was particularly striking in Punctured Sculpture, an exquisite element of the Expand, Expand chapter, consisting of a cache of metallic, gem-like shards planted atop blocks of foam. In addition to its cosmetic appeal, this work allured because ultimately, it constituted the trace of an act of destruction which itself was laden with significance.The fragments were smithereens of a shattered thermos flask, their implosion, literally, the voiding of a vacuum or absence – that is, the production of an artwork via the elimination of a cavity containing nothing.

Contrasting with the lateral spread of many of the floor-based works in this exhibition was Beam Hang, consisting of a shaft of fluorescent neon ‘looped’ over a ceiling beam that hung in a downward strike of 3000 volts. Entering the main gallery, one was enticed immediately by this hypnotic nimbus. The strange ethereal quality of this electric totem illustrates Canell’s ability to direct attention to the way in which the mundane ubiquity of the familiar and the relied-upon confines the potential of that same thing’s ‘true’ character. Electricity’s extension of our communicative abilities and cognisance has resulted in a situation in which the majority of humans are entirely dependent upon waves and networks of ever-ready electromagnetic energy. The corollary of this century-long progression has been the obscuring of the theophanic properties of electricity and the overshadowing of any sense of enchantment. In seductively arousing a sense of sirenic intrepidation, Beam Hang – indeed all of the works in this exhibition which include electric pulsations as an integral component – underscores the fact that there remains something fundamentally strange and mysterious about the human connection to the vast grids and networks of harnessed and decentralised power that span and gird the globe.

Devices such as Beam Hang, which illustrate fundamental scientific principles while remaining visibly vulnerable and unstable, are common in Canell’s practice, drawing attention to the precarious oscillations of both the natural and man-made systems upon which human survival depends. A tone of volatile instability was particularly evident in an intricate accumulation entitled Nerve – an encounter between a steel tripod, bone, wire, magnets, wind chimes and an electric pump. The tintinnabulations of the chimes, activated by the electric pump, seemed congruous with the skeletal frailness of this freestanding musical-visual construction. Like Beam Hang, Nerve’s fragility exposed the functioning conduits and systems of energy as mutable – susceptible to malfunction and external interference. There was a distinctively anatomical character to Nerve (also evident in the piece entitled Like Hands, Like Feet, Like Eyelids, Like Rows of Upper and Lower Teeth) that brought to mind the human brain’s status as another electrically and chemically active device, accentuating how every move and thought is effectively the result of the electrical phenomenon of neurotransmission.

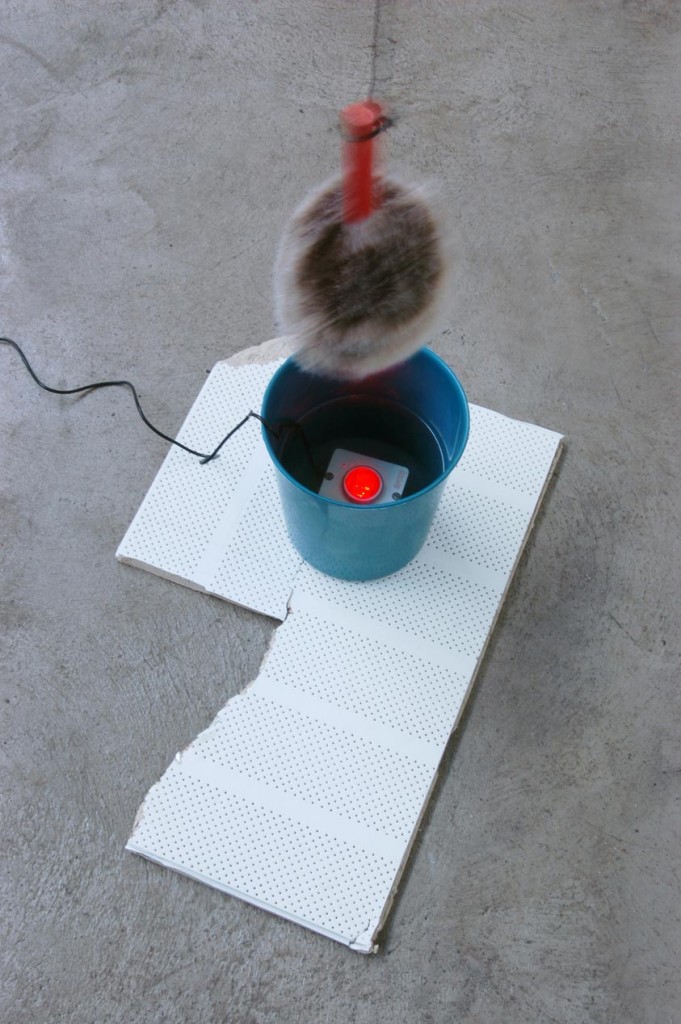

Immersing the space in uncontainable waves of light and sound, Canell enveloped the heterogeneous components of this exhibition – and the visitors who entered it – into a unified continuum.This was apparent in the case of the piece Bucket (Wool-gathering), a compact sculpture that, in addition to emitting a rumble at regular intervals, produced a spectral brume of low-lying mist, which the movements of passing viewers caused to pullulate eerily.These same waves connect Canell with a lengthy narrative of categories of artist, scientist and occultist.4 Canell’s work, like that of her antecedents, annunciates the concept that instead of setting magic and science in opposition to one another we would be better to draw a parallel line between them as two modes of understanding.5 Embracing this daunting but rejuvenating idea transmitted by Canell’s bricolages, one can return to the scrap-heaps of hypermodernity galvanised, with the enthusiastic, inquisitive eyes of a newcomer, newly aware of the pitfalls presented by those groundless structures of feeling (such as that which correlates truth with technology) which over time become inherited, accruing the status of fact.

(1) Berthold Brecht, interview with Luth Otto, in Brecht on Theatre: The Development of an Aesthetic, ed. and tr. by John Willett (Hill and Wang, New York, 1964), pp. 70–71

(2) Nina Canell in conversation with the author, January 2008

(3) Nina Canell, ibid

(4) Inadvertently addressing the relatively recent schism between science, magic and art, Canell evoked the zealous writings and experimentations of visionary scientist Nikolai Tesla (1856–1943), whose practice – while founded upon rigorous technical acumen and logical scientific expertise – was akin to that of an artist channelling supernal and esoteric energies, the potential of which was illimitable. In Tesla’s ‘On Electricity’, published in The Electrical Review, January 27, 1897, he stated “Electrical science has revealed to us the true nature of light […] Electrical science has disclosed to us the more intimate relation existing between widely different forces and phenomena and has thus led us to a more complete comprehension of Nature and its many manifestations to our senses. Electrical science, too, by its fascination, by its promises of immense realisations, of wonderful possibilities […] has attracted the attention and enlisted the energies of the artist; for where is there a field in which his God-given powers would be of a greater benefit to his fellow-men than this unexplored, almost virgin, region, where, like in a silent forest, a thousand voices respond to every call?”

(5) This idea is developed in depth in Claude Levi-Strauss’s The Savage Mind (University of Chicago Press; first pub- lished in 1962), in which he argues that art lies somewhere between science and magic.