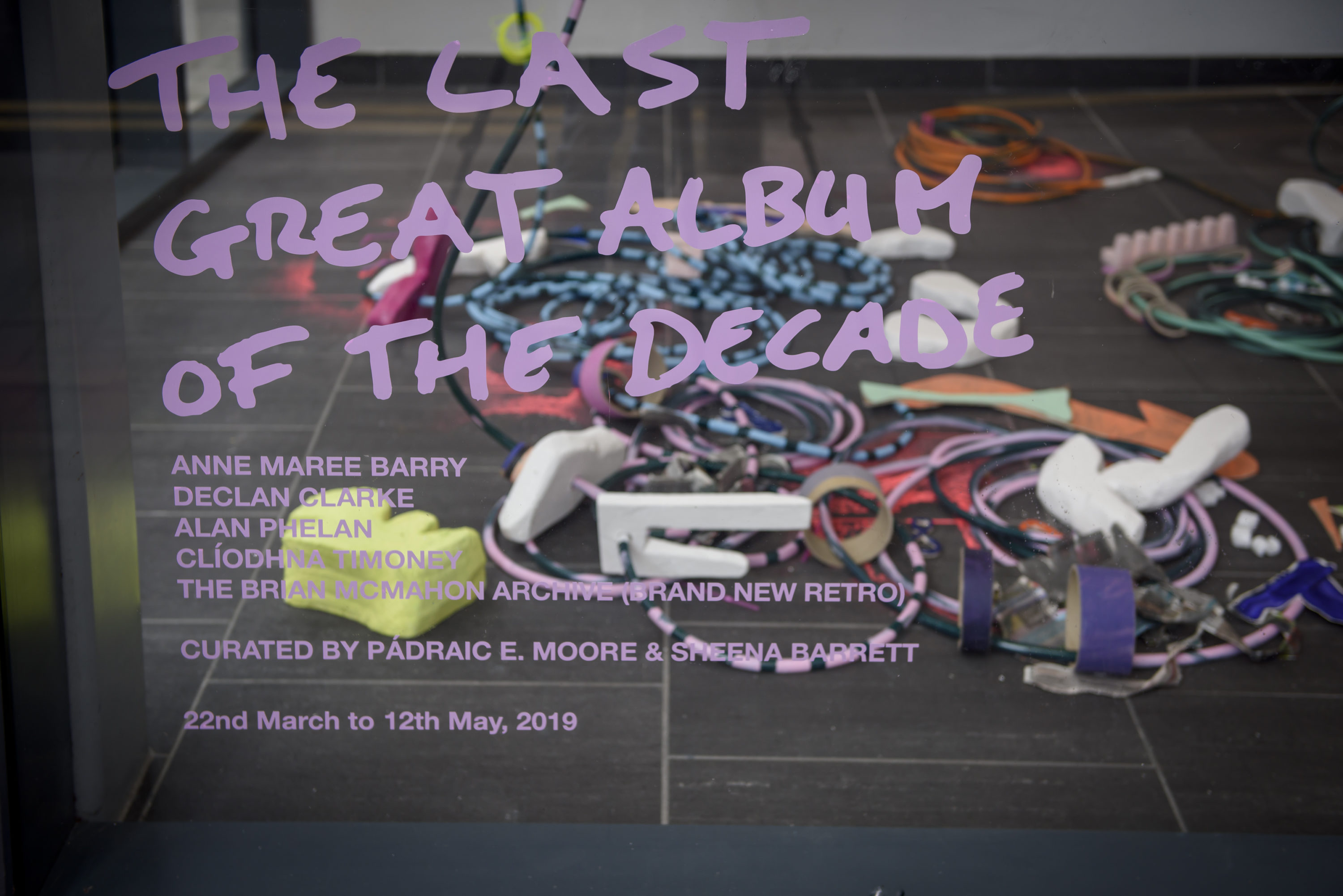

The Last Great Album of the Decade

The Last Great Album of the Decade

Anne Maree Barry, Declan Clarke, Alan Phelan, Clíodhna Timoney, The Brian McMahon Archive (Brand New Retro)

March 22 – May 12 2019

The LAB Gallery is pleased to present the Last Great Album of the Decade in association with Musictown.

The exhibition is co-curated by Pádraic E Moore and Sheena Barrett and features new work by Anne Maree Barry, Declan Clarke, Alan Phelan and Cliodhna Timoney. The title is both suitably brash, claiming greatness, and mournful, in suggesting that it can’t be surpassed.

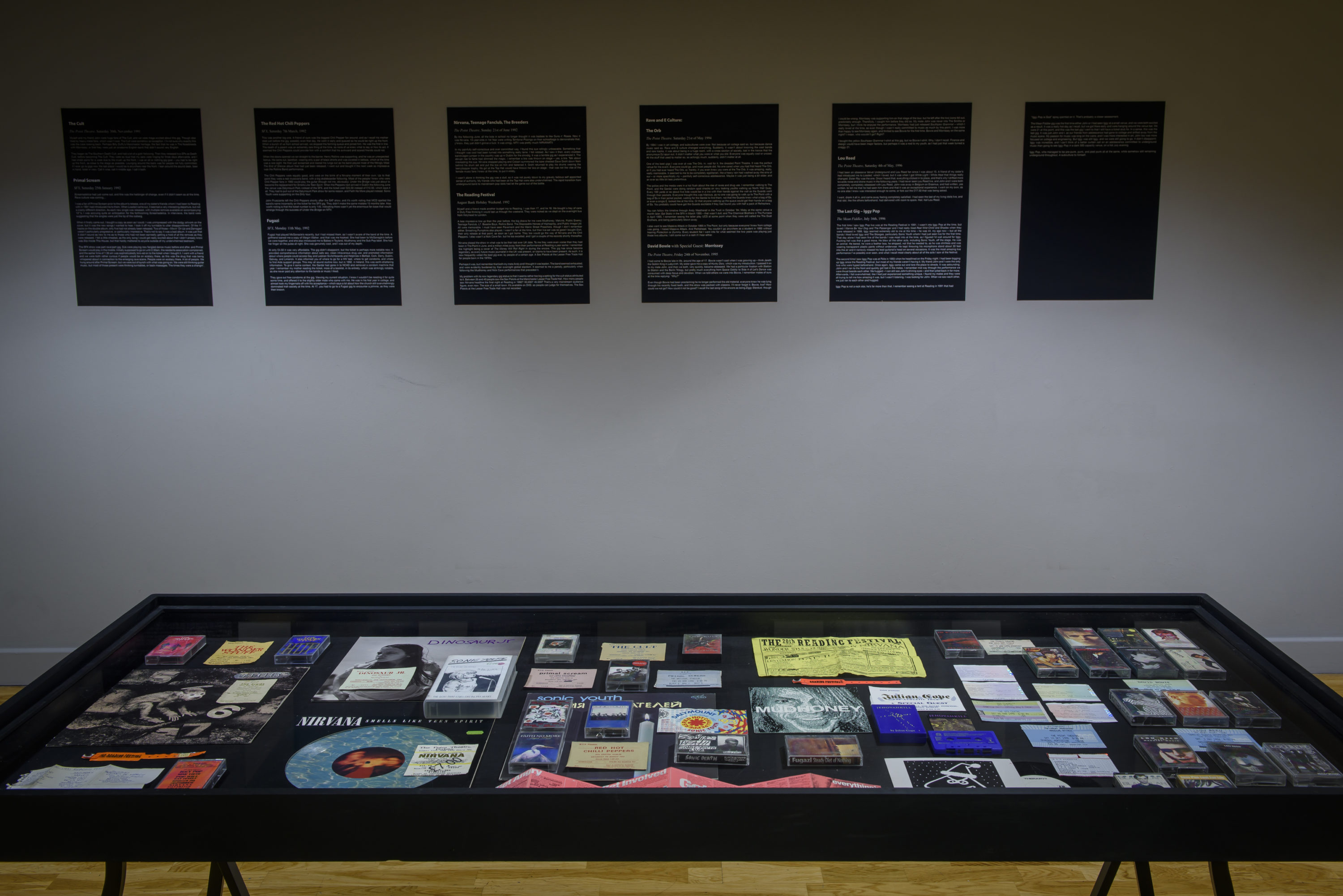

This exhibition seeks to celebrate the musical relic and souvenirs of the subculture, taking in gigs in the 90s, a selection of zines from Brand New Retro, the Dublin rave scene in the early 2000s, the demise of rural nightclubs and journeys from early photographic experiments through to the potential backdrop for a new music video.

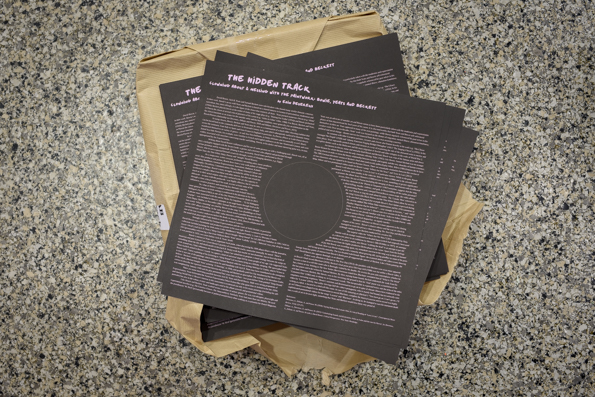

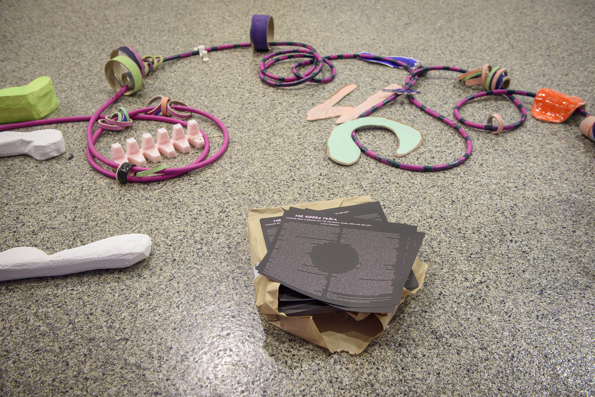

Stepping into the Music Library at the Central Library in the Ilac Centre visitors can skip through genres via the biographies of musicians, sheet music, vinyl and cds and we’ve also planted copies of Eoin Devereux’s hidden track, along with Audrey Walshe’s botanical response to the show.

In partnership with Musictown, we are also running two very special events, a screen-writing workshop for teenagers with Anne Maree Barry in the Music Library and an historial music tour of the city with Donal Fallon. Bookings through Eventbrite. In addition to Dublin City Council this exhibition has been supported by the Arts Council of Ireland, Inspirational Arts and Oonagh Young Gallery. We would also like to thank Rebecca O’Dwyer, Mark Clare, Liam O’Callaghan, Leagues O’ Toole and Amy Nix (MusicTown) and the Gallery of Photography.

Essay by Pádraic E Moore and Sheena Barrett

The term ‘album’ was adopted into English in the seventeenth century from the Latin phrase album amicorum (meaning ‘album of friends’) to describe a book that collected autographs, drawings or poems. At the beginning of the twentieth century, the term became shorthand for the phonograph record; in the years that followed, it also came to refer to a wave of new formats that arrived in quick succession: cartridge, cassette, compact disc, and the (relatively short lived) MiniDisc. From the sixties onwards, the album became the supreme mode of musical expression, the place where artists pushed boundaries, took risks, and evolved new genres. Today, musicians are still doing this, of course, but the way we listen to recorded music has drastically changed. As one consequence of online streaming, albums are being increasingly replaced by private, personalised playlists. In this, the coherence or intended sequence of an album is undermined, along with, quite possibly, the communal potential of the music itself. Yet while the declining centrality of the album as art form and commodity has changed how music is collected and consumed, there is no doubt that recorded music is as capable as ever of raising consciousness – of taking us out of – and beyond – ourselves, and bringing us together. And there are still legions of us listening to new albums, on repeat, for days on end.

If this exhibition was an album, it would be heterogeneous and epically sprawling: a four-sided affair, maybe something like Prince’s Sign ‘O’ The Times or The Orb’s Adventures Beyond The Ultraworld, featuring a hallucinatory sleeve that you and your friends would stay up all night studying. Obviously, this exhibition – is not – an album; but several of the elements from which it is comprised, such as the hidden track — here taking the form of an essay by the sociologist and writer Eoin Devereux – are conceived in an enthusiastic nod to the format. Like all the best albums, the exhibition is founded on the implicit conviction that music can be a supreme connector, creating hives of likeminded folk and offering the chance of escape from an antagonistic society. At its heart, the project is a testament to musical culture as an unparalleled catalyst for social exchange.

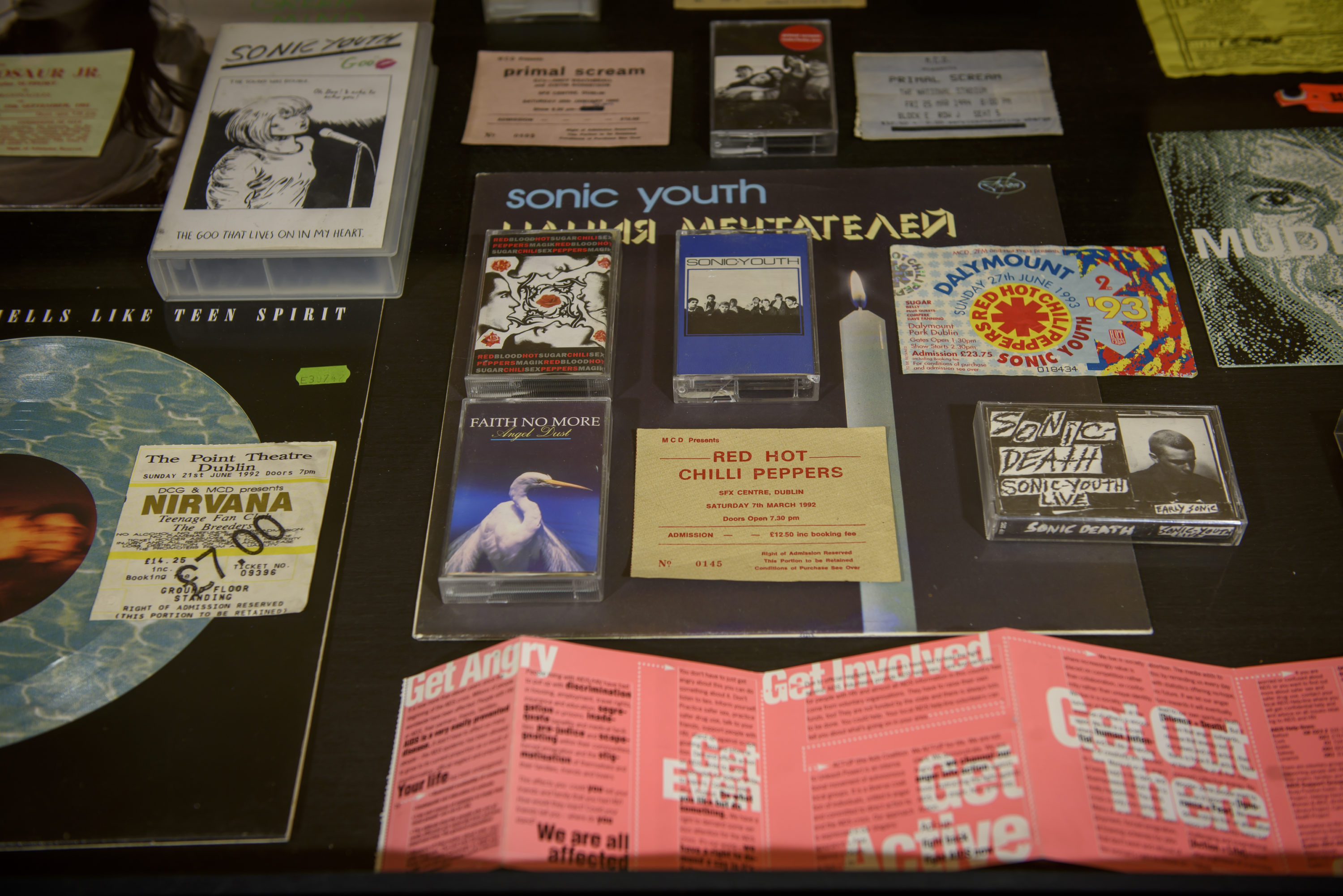

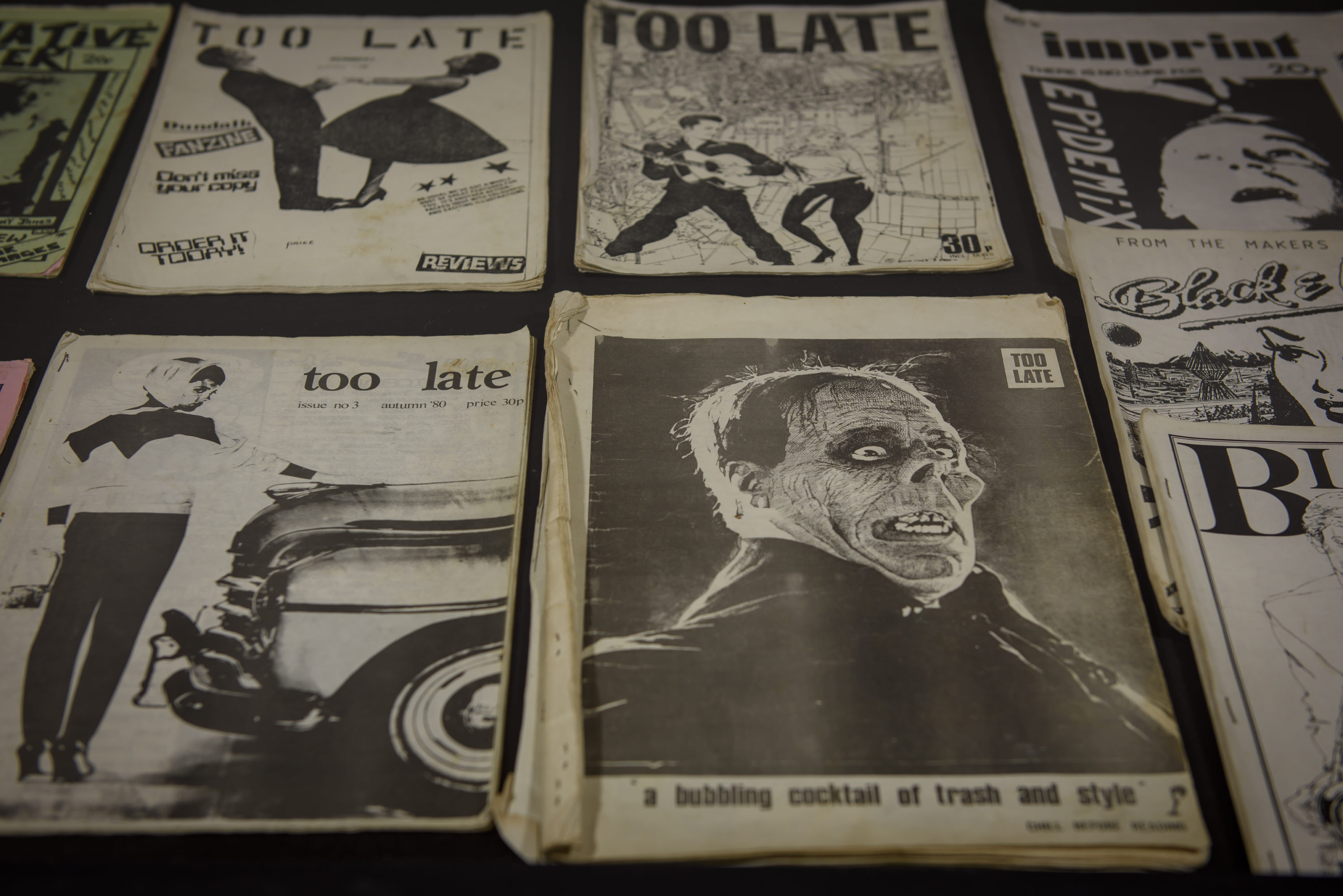

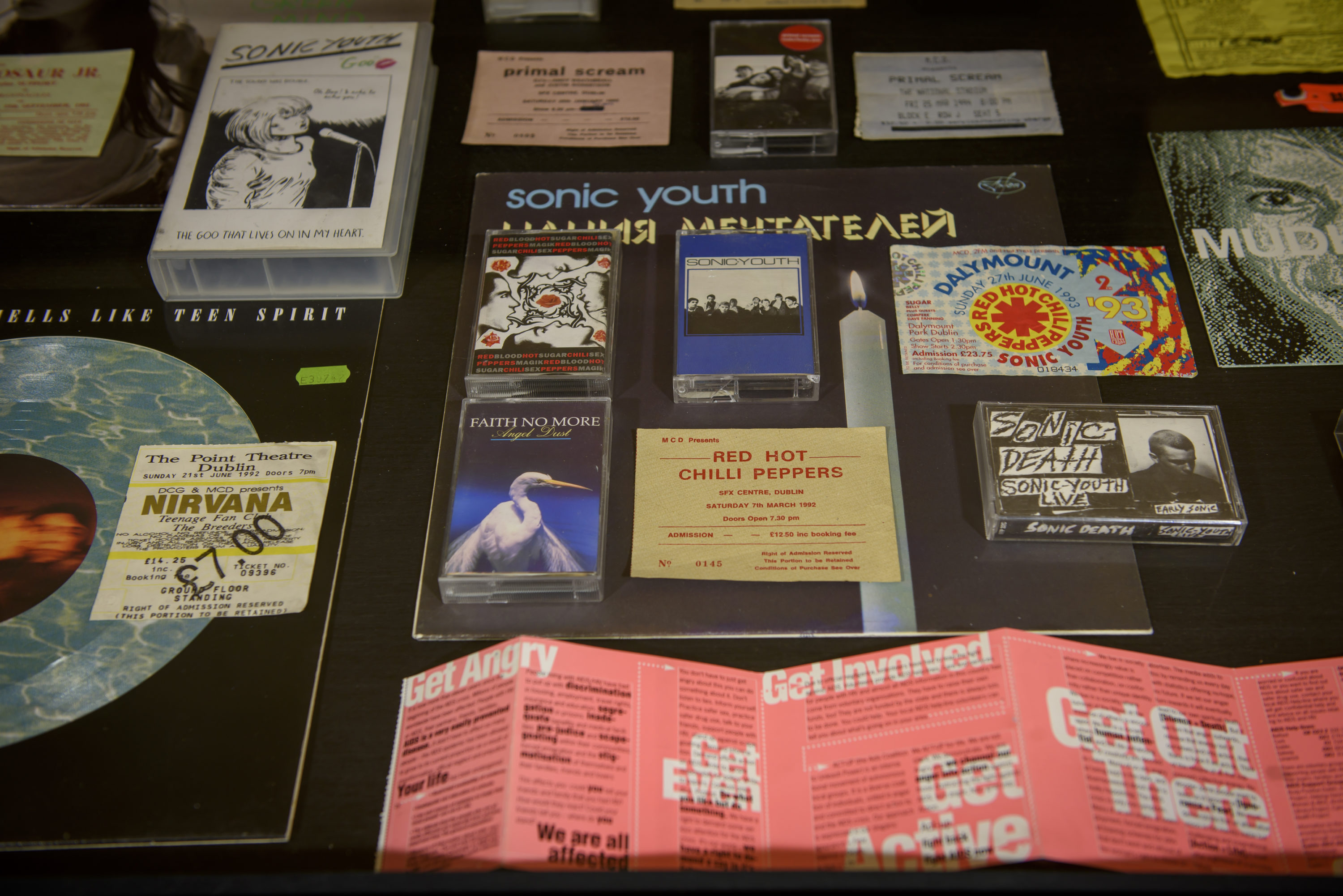

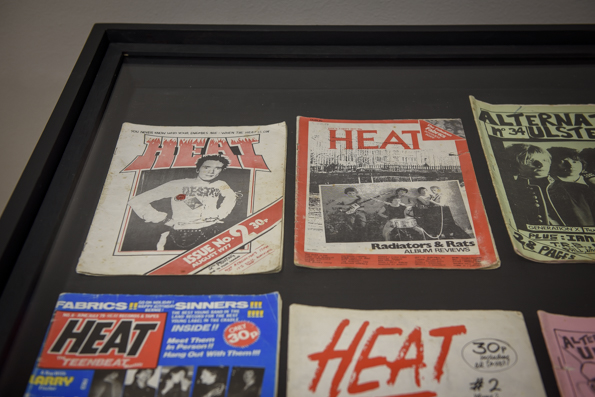

True believers, we celebrate the musical relic and souvenirs of the subculture. Declan Clarke recalls gigs he attended in Dublin in the early nineties; here, he shows an array of ticket stubs and t-shirts collected all those years ago. Of course, these objects hold personal significance for the artist. Yet from a social history perspective, they also represent a seminal moment in the transition of youth culture, at which popular musical taste moved rapidly from indie rock into electronica, and rave scenes emerged. Photos of Clarke taken surreptitiously by his late father in 1991 show the artist surrounded by his posters and cassettes, suggesting how the adolescent’s journey of discovery for belonging in musical worlds can provide a lifelong source of enthusiasm. Alongside Clarke’s paraphernalia, a selection of zines from the Brian McMahon Archive (Brand New Retro) offers insight into how the range of music-related printed matter produced and disseminated offered a focus for communal exchange. While the production quality of these relics varies hugely, it is clear that the determination and desire to contribute to a dialogue and to express enthusiasm is much more urgent than any questions of technique or finish. The real point of these objects was to pass them on in spirited conversion attempts, or to argue about them with friends.

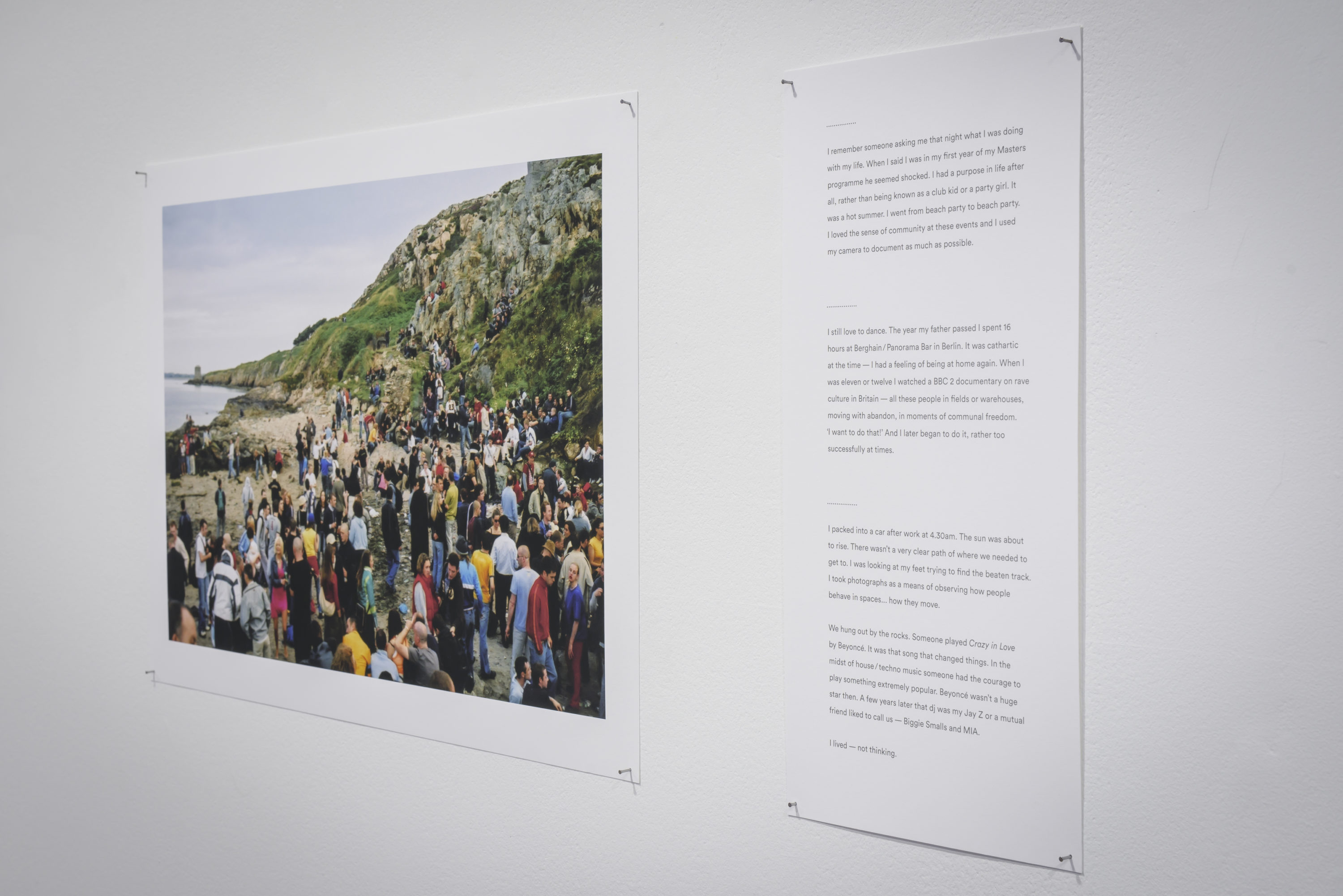

Although different in many ways, the potential and the power of the DIY ethic is also discernible in a series of photographs taken by Anne Maree Barry. These images of underground self-organised parties that took place in the summer of 2003 show a large group of young people sprawled over what might be an island, just as first light breaks. Such parties emerged from a culture of self-organisation and self-sufficiency, with an emphasis, as with their rave precursors, upon inclusion and togetherness facilitated (primarily) through music. While the work could be described as documentary in nature, it should be noted that Barry, as opposed to a voyeur, was an active participant in these events. Looking at them now, it’s striking that no one is using a phone. The images take on a nostalgic tinge, accentuated by the image quality, which conveys a documentary realism in comparison to the filtered smartphone lens used to share experiences with a community not present via Instagram. The parties captured in these photos were relatively rare in a city like Dublin. Indeed, as the city recovers economically and becomes less affordable, such gatherings are becoming even rarer still. Regulation and legislation along with changing land use have put increasing pressure on the viability of nightlife and club culture. The critical nature of this situation has led to the Give Us the Night campaign, who are lobbying to have the value of nightlife, economically and socially, recognised and to counter more conservative leadership that views nightlife and club culture as insignificant or even deviant.

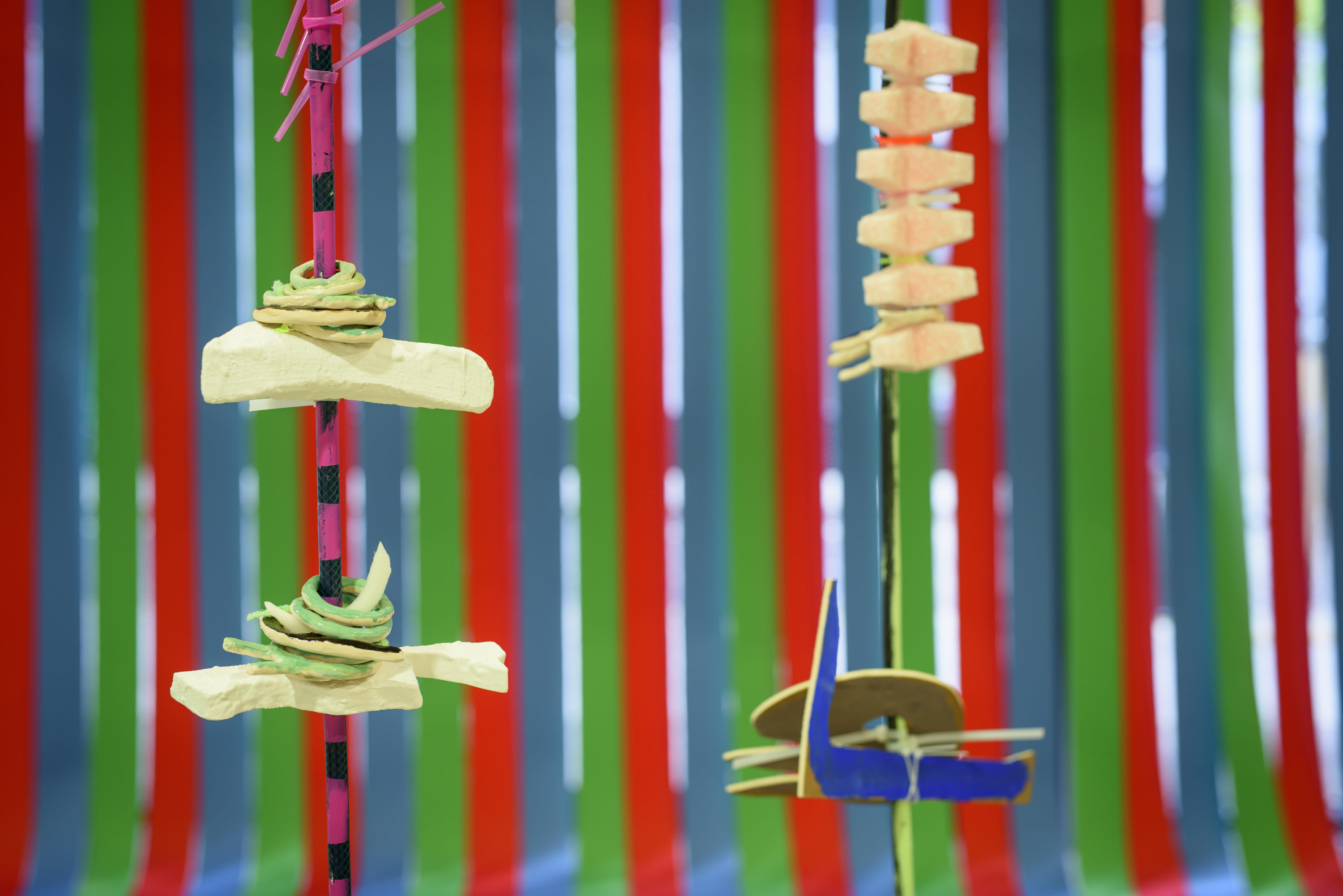

While the aforementioned artists focus on the material remnants and the social milieu that forms around music, others respond to and ‘inhabit’ music much more formally, making work concerned with characteristics aligned with its production: Alan Phelan’s visually striking installation entitled A Joly Screen, the background, for example, made from material usually used in backdrops for photo shoots. In this instance, the RGB ‘curtain’ has been conceived as a backdrop for a music video. Alongside the lastolite stripes (that partially obscure the interior from the exterior) a mattress and some other ‘props’ charge the installation with narrative possibility. As with much of Phelan’s earlier body of work, A Joly Screen, the background, is informed directly by research into historical narratives, and the desire to interrogate the official aspects of these stories[1]. In creating this speculative music video set, he aims to create a site of possibility and potential. Ultimately, this demonstrates his interest in the provisional nature of an artwork as never quite complete, never fully resolved, just about there but not fully. A piece of electronic music composed to accompany Phelan’s mise en scène — something like the excerpt of a soundtrack to an as-yet unmade film — will be presented on the exhibition’s opening night.

A new body of sculptures by Cliodhna Timoney refers to several nightclubs in her hometown of Letterkenny in County Donegal, many of which flourished in the mid to late nineties. Now, some of the clubs are defunct, while others are just about holding on, in a state of clear dilapidation. The titles of Timoney’s assemblages — such as The Golden Grill, The Pulse and Voodoo – are taken directly from the names of these maligned venues. Much like the broader county itself, they have been left behind in the wake of the latest crash, or rendered unviable for the simple lack of young people still living in the area. Her sculptural accumulations are both an homage and formal interpretation of these environments of music and hedonism, where people go to lose themselves and engage in dance-floor catharsis. Scattered throughout the gallery, Timoney’s variegated assemblages suggest the detritus that remains in the aftermath of the party: when the lights are brought up cruelly to mark the night’s end, dazzling us into blindness.

Beyond the original desire to explore collections of musical ephemera, along with artists interested in using music as a referent, much of the thinking around this project has been informed by the writing of cultural theorist Mark Fisher. While his scathing if accurate analysis of contemporary society is somewhat dispiriting, his writing is always balanced by enthusiasm. Nowhere is this more discernible than in his intense, and at times somewhat unlikely, appreciation of popular music. In particular, he was fascinated by popular music’s capacity for “nihilation; the producing of new potentials through the negation of what already exists”[2]. A key concept propagated by Fisher is what he described as ‘popular modernism,’ referring to a kind of culture — often found in music — that merged experimental elements with mainstream modes of production and dissemination. Fisher’s writing undermined the delineation of culture into categories of ‘authentic’ and ‘popular’ and implied that pop culture can also function as a critique, – as opposed to affirmation – of the society from which it emerges.

A similar desire to emphasise the importance of popular music was conveyed by Dan Graham in his seminal video essay Rock My Religion from 1985. At that time, when convergences between visual art and music were reaching unprecedented synergistic peaks, Graham’s essay sought to examine and underscore the importance of certain musical genres of the preceding decade. Proposing a lineage of rock music from the sixties back to certain forms of ritualistic practice and religious worship such as that of the (dancing) Shakers and Quakers, the essay shows popular rock music’s deep capacity for facilitating certain forms of enlightenment and egalitarian togetherness. As he neatly puts it in the essay’s closing lines: “if art is only a business, as [Andy) Warhol suggests, then music expresses a more communal, transcendental emotion which art now denies”. In this sentiment, Rock My Religion is a crucial touchstone for The Last Great Album of the Decade. Much like the film, this exhibition revels in those sacral aspects of popular music that that have (perhaps necessarily) been discarded or denied from the sphere of visual art. It makes room to consider, quite seriously, the profound devotion of the fan, the surrender to cultish following, the fetishistic interest in memorabilia, the communality of the sweaty fray, and perhaps, most importantly, the desire to get lost in “The Thrill of it All”[3].

The Last Great Album of the Decade is co-curated by Pádraic E. Moore (independent curator) and Sheena Barrett (Assistant Arts Officer at Dublin City Council/The LAB Gallery Curator).

[1] This work is informed explicitly by Phelan’s ongoing research into John Joly (1857–1933) one of Ireland’s most eminent scientists of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries who made important discoveries in physics, geology and photography. Phelan’s work references the ‘Joly colour process’, one of the first practical methods for colour photography that entailed the use of glass photographic plates with fine vertical red, green and blue lines printed upon them.

[2] k-punk: The Collected and Unpublished Writings of Mark Fisher (2004-2016) edited by Darren Ambrose with Simon Reynolds. Repeater Books. 2018. p.321

[3] The Thrill of It All is a single by Roxy Music featured on their 1974 album Country Life.