Tour Donas

Love and Crime and Collaboration

The work of Lucy McKenzie draws on episodes in the history of art and design in which ideology and aesthetics intersect. She adapts extant forms, inflecting them with contemporary nuances and focuses on vernacular visual vocabularies that emerge in peripheral, provincial locations. This emulation of historical idioms stems not from a wish to critique but a desire to understand the past. She describes this relationship with her predecessors as “inhabiting their methodology” and “channeling their way” (1). McKenzie’s investigation of appropriation, authorship and the hierarchies between artforms often extends to her acquiring skills relating to the applied arts. A recent example of this is the handmade replica McKenzie made of Madeleine Vionnet’s Cubist-inspired L’Orage dress from 1922, which can be seen in the promotional image for this exhibition.

In 2007 McKenzie enrolled as a pupil at The Van der Kelen-Logelain Institute in Brussels. Founded in 1882, this private school provides students with intensive courses in traditional decorative painting techniques including faux wood and marble, advertising lettering, illusion painting, stencilling, and gilding. As McKenzie has written, this institute “not only retains the natural materials, techniques and aesthetics of the 19th century but also the ethos, with its authoritarian atmosphere and almost impossible workload, it was very different to a course in painting at a contemporary art school. Your paintings spoke for themselves and you were respected if not rewarded for hard work; no theoretical gymnastics could win you ground. We were taught pride in our vocation and work and self-respect as skilled artisans. This was to be reflected in our clean and crisp white work coats and discrete deference towards patrons and co-workers” (2).

The work coat or smock is a motif that recurs throughout this exhibition at Temple Bar Gallery + Studios. Both literally, in the form of pieces from McKenzie’s own collection, and via representation in the form of a screen print on silk entitled Workcoat (2009). Also included is a reproduction of a watercolour by Mainie Jellett depicting a stylised figure wearing a work coat (3). McKenzie has written about the symbolism of the work coat in her 2008 essay ‘Rodchenko’s Workers Suit Had No Fly’. According to McKenzie, the work coat can “simultaneously suggest both drudgery and liberation (and) signifies the bohemian emancipation of the women who were able for the first time to enter public and private art schools at the end of the 19th century. Whether this is the group of artists and designers in the circle of Charles Rennie Mackintosh at the Glasgow School of Art, known as the ‘Glasgow Girls’, or Käthe Kollwitz posing with a beer tankard in her studio, the image of the smock-wearing ‘New Woman’ is iconic” (4).

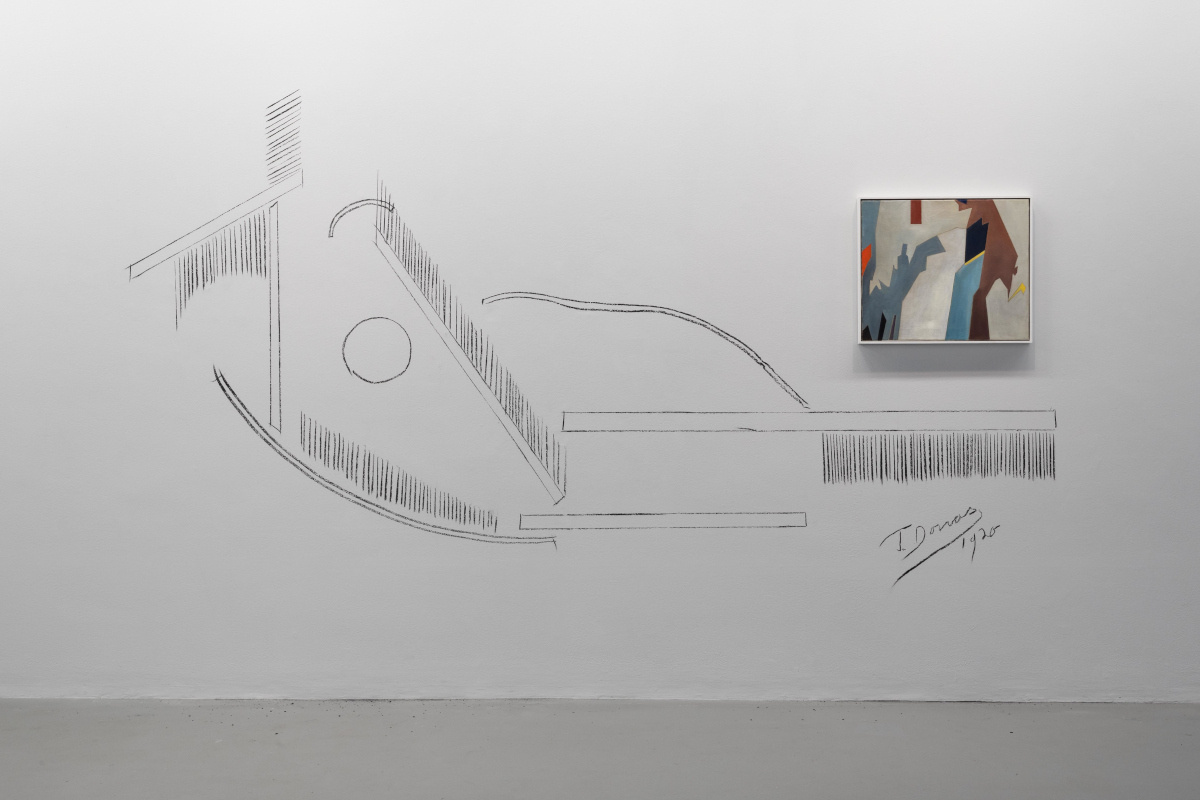

n the most well-known image of artist Marthe Donas (1885-1967) taken around 1922, she is photographed in her Paris studio, wearing a painter’s work coat. She looks directly at the camera and is sat in front of her easel, surrounded by a selection of predominantly Cubist compositions. Donas spent two years in Dublin from 1914 and studied under Sarah Purser at the cooperative stained-glass studio, An Túr Gloine (The Glass Tower). Although little is known of Donas’ time in Dublin, it has been established that she produced several pieces of stained glass for ecclesiastical settings, the whereabouts of which is unclear. Donas left Dublin after Easter 1916 and relocated to Paris where, in an effort to gain traction in a male-dominated art world, she adopted the androgynous pseudonym ‘Tour Donas’. It was at this point that Donas began executing her first abstract compositions influenced by the sculptor Alexander Archipenko (5).

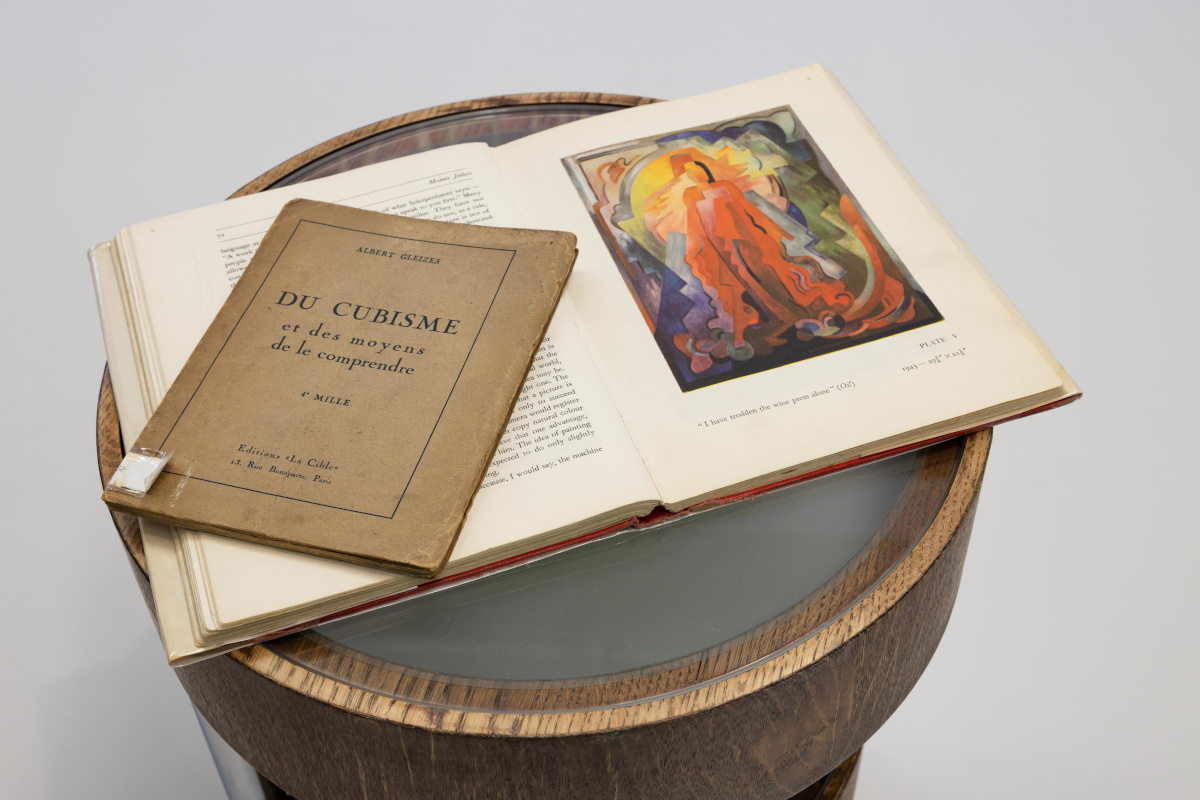

The vocabulary Donas developed is comparable to that of Mainie Jellett and Evie Hone, both of whom also believed in the Utopian possibilities of the universal language of analytical Cubism. Like Donas, Hone was also associated with An Túr Gloine and she would go on to receive many major stained glass commissions for churches in Ireland and the UK. Donas’ legacy exemplifies the personal and cultural connections that existed between Ireland and the rest of Europe in the 1920s. Although her reputation has to some extent been recuperated in recent years she remains largely unknown outside her native Belgium, despite the fact that she collaborated with and exhibited alongside many of the leading abstract artists of the 20s. Like Jellett and Hone, Donas was significantly influenced by the teachings of Albert Gleizes, who had been affiliated with the influential group of artists and theorists known as Section d’Or aka ‘The Puteaux Group’ (6). A unifying tendency in the work of Donas, Hone and Jellett is the integration of Cubism with Christian iconography. Included in this exhibition are two books that originate from the personal library of Hone, which highlight the theoretical underpinnings of Cubism and the fact that such ideas were frequently disseminated via pamphlet (7).

The other key referent of this exhibition is Villa de Ooievaar, a listed Modernist building in Ostend dating from 1935. McKenzie purchased the villa in 2014 and is now faithfully restoring it as an active site where the strands of her multidisciplinary practice can be united. While the villa is being renovated in line with the original materials and design, McKenzie is also incorporating new elements and objects that will transform the house in subtle ways. In effect, the house is being treated as an appropriated artefact, the idiosyncrasies of which are feeding back into her work, providing a site for new creation. The modernist home, whose name translates as Villa Stork (the bird often associated with the delivery of babies) was designed by the Flemish architect and designer Josef De Bruycker in 1935, amid the rise of authoritarianism in Europe. Commissioned by a Catholic doctor and his wife to accommodate their family of fifteen and his adjacent medical practice, the villa remained in the family’s hands until the mid-1990s. The two round side tables included in this exhibition were both made for De Ooievaar by McKenzie. They both contain trompe l’oeil paintings known as quodlibets – compositions depicting quotidian objects arranged in a seemingly haphazard fashion, scattered on a tabletop. or pinned into a board (8). These particular quodlibets bring together items that contemporaneous to the house, such as a monument to Flemish nationalism, a postcard of an artwork by the aforementioned Marthe Donas, and a souvenir powder compact from Glasgow’s 1939 Empire exhibition, with an object from McKenzie’s own life; a multipass for her local swimming pool in Brussels.

This exhibition also includes ten photographs of Villa de Ooievaar taken by Kristien Daem. These images reveal the extent to which the house was conceived as gesamtkunstwerk that fused innovative influences (particularly those of De Stijl) with traditional, even conservative, elements. This is particularly evident in Daem’s photographs of the stained glass windows that are located throughout the house. The master bedroom is decorated with three stained glass windows of religious scenes with a particular significance to the original occupants: St. Camillus, the patron saint of doctors, and St. Margaret of Antioch, the patron saint of childbirth, whose first names were shared by the heads of household. In an opulent downstairs hallway a street-facing stained glass window depicts a particoloured seascape while a more private window facing onto the garden contains more loaded visual codes. Art historian Leah Pires (who describes the villa as an ‘ambivalent object’ typical of those McKenzie summons in her work) points out that the “window visible only from the back garden is emblazoned with the soaring bird logo of the youth league of Verdinaso, an extreme right-wing Flemish political movement that, in 1941, merged with the Flemish National League, the leading collaborator with Germany during the occupation of Flanders during World War II. The private window enshrines political allegiances within the family home. Against this backdrop, the Villa De Ooievaar embeds homages to the nuclear family, Catholicism, Flanders, and far-right politics within an avant-garde structure, making it an ambivalent portrait of its time that continues to raise challenging questions about the relationship between aesthetics and politics today” (9).

McKenzie’s work demonstrates how the history of art can be analysed and activated in a manner that is at once rigorous yet subjective. She reinvigorates archival fragments whilst devising a lexicon that is seductive yet self-reflexive, using visual pleasure to draw attention to the systems of power at play in the art world as well as broader society. Also captivating is her ability to draw attention to the way local, regional permutations of international styles can reveal information about the socio-political context in which they formed. McKenzie’s oeuvre is shaped not only by technical skill and stylistic verve but insatiable curiosity and a commitment to ethics of integrity and a generosity of spirit. At the heart of her work is an interrogation of what the role of an artist might be in the 21st century. As endeavours such as those with her design and manufacturing project, Atelier E.B, highlight, she is committed to the ideological implications of collaboration. She perpetually negotiates boundaries between commerce, popularity and pedagogy and is staunchly resistant to the risks of being co-opted by a corporatism that demands the surrendering artistic autonomy. As she stated several years ago, “I do not wish for Victorian values; I merely propose that the independent artist need not necessarily be a global nomad bureaucrat. Rather something closer to the classical artisan, but one who nevertheless creates their own language, relationship to commerce and self-definition. Social engagement within contemporary art is itself a form of trompe l’œil”.

– Pádraic E. Moore, 2021

(1) Leah Pires, Break and Enter / Rent to Own in Lucy McKenzie: Prime Suspect, Museum Brandhorst, Cornerhouse, 2020, p.305-319

(2) Lucy McKenzie, ‘Canvases Stretched in a Studio Far Less Convenient than One’s Own’, in Chêne de Weekend (exh. cat.), Cologne: 2009, p7 -15.

(3) This watercolour is assumed to be an unused advertisement for Winsor and Newton paints, dating from 1930.

(4) Lucy McKenzie, Rodchenko’s Worker’s Suit Had No Fly; Afterall, 2013-09, Vol.34, p.56-61

(5) This exhibition is named Tour Donas for several reasons. To some extent, it is a homage to an artist who has thus far been excluded from the canon. Both McKenzie and I share an interest in the work of Donas, which has featured in several of McKenzie’s paintings. Aside from these references there is the attractive ambiguity to the words, with Tour suggesting movement, freedom and the attainment of new experiences.

(6) This Paris-based association of Cubist painters were active from 1912 to about 1914. The principal members of the group were Robert Delaunay, Marcel Duchamp, Raymond Duchamp-Villon, Albert Gleizes, Juan Gris, Fernand Léger, André Lhote, Jean Metzinger, and Francis Picabia.

(7) The Hone collection is now held by NCAD who kindly made these two publications available for this exhibition.

(8) Traditional quodlibets are always tabletop compositions, but McKenzie also uses the term for her pinboard works.

(9) Pires, ibid